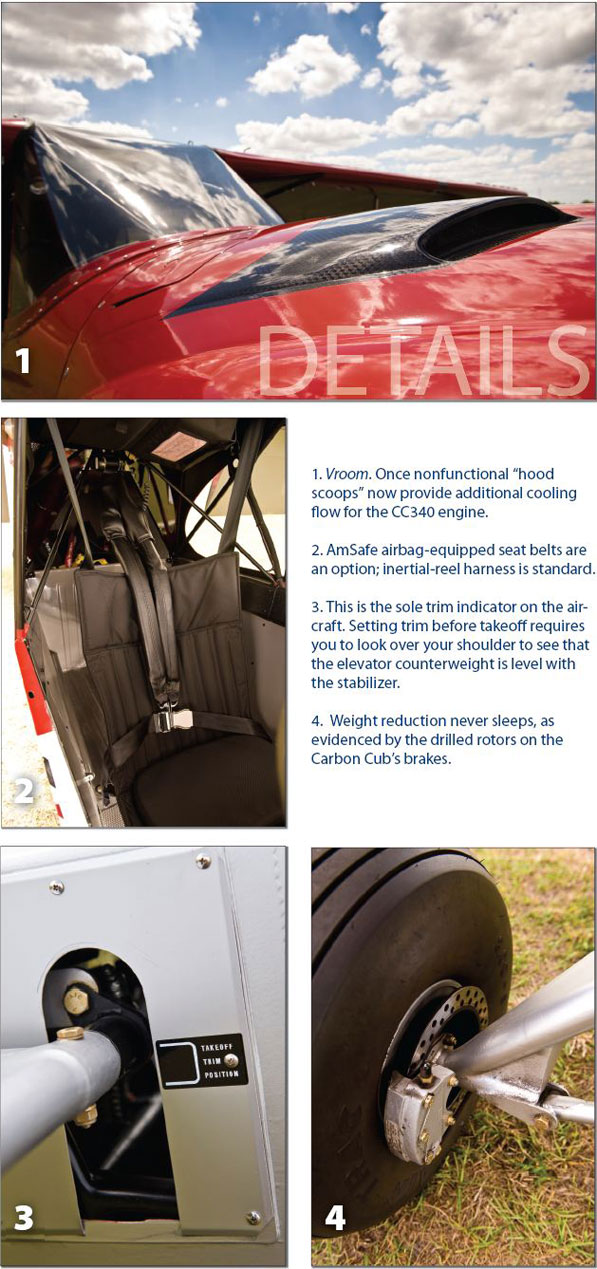

After a morning of flying the Carbon Cub SS low over the Yakima River, to outrageously short landings at a marvelous grass strip followed by several eye-popping takeoffs, three of us stood in one of CubCrafters’ hangars casually discussing the merits of the venerable design. It’s 80 years now since C.G. Taylor penned the E-2 Cub, a rugged, simple airplane perfect for its time, and yet the design lives on…indeed, it’s thriving as both an Experimental/Amateur-Built design and as a Light Sport Aircraft.

Modern avionics adorn the Carbon Cub’s stylish panel. Various packages are available from the company, but if you build your own, you can follow any path you choose.

We’d borne witness to the strengths of the Cub, enjoying the flight regimes where the design excels—low-altitude cruising, dropping into and then charging back out of short fields, enjoying the view under a 2000-foot overcast that might have been up to 15,000 feet for all we cared. Tight patterns, trees all around, working an airplane for all it was worth—not at all like a feet-on-the-floor shunt in the flight levels. In retelling the morning’s flight, CubCrafters founder Jim Richmond, at the helm since 1980, nodded quietly and paused before the summation, saying, “Well…that kind of flying? It’s a Cub thing.”

Joining the Cub Club

Richmond’s company started rebuilding bent and broken Cubs, a cottage industry but a busy one. The kind of aviating Cubs do places them in proximity to damage factors—flying off an Alaskan sandbar is a world away from your 5000-foot paved strip, just as hauling out the spoils of the hunt is a solar system distant from jetting the family to the Bahamas.

CubCrafters eventually grew into a successful refurb shop, something it continues today, and then, when newish Super Cubs became increasingly hard to find, launched the Top Cub. Built on a regular FAR Part 23 type certificate, the Top Cub is a PA-18 Super Cub improved—lighter, stronger, refined. All for a base price of $205,480.

The Cub stance. The Carbon Cub SS, from which the EX is drawn, is clearly a Cub with modern touches such as the svelte cowling and composite prop.

You can fly with the window open, and you might cuss the door as you scramble into the front seat, but you’ll be happy once you get there.

Seeing the potential of the Light Sport Aircraft segment, Richmond and company went to work on a lightweight Cub; the latest iteration is called the Carbon Cub SS. Sold as a ready-to-fly SLSA, the SS differs from the earlier Sport Cub S2 in myriad ways, but particularly ahead of the firewall. Where the Sport Cub uses the Continental O-200, the SS features an in-house-built version of the Engine Components, Inc., Titan engine called the CC340. At its heart, this is the O-340 “stroker” that ECI developed using an O-360 crankshaft and O-320 taper-fin cylinders. It’s rated at 180 horsepower for takeoff and 80 hp continuous. Why? See the sidebar, “How Do They Do It?”

Developed to Be Light

Understand the concept here: Build the sveltest Cub you can with the most powerful engine you can shoehorn into it. In a sense, the restrictive LSA rules have helped the homebuilt version. To make the Carbon Cub SS legal, the empty weight had to come in under 900 pounds, no small feat with an airframe this large and an engine so powerful. To make the goal, CubCrafters has been relentless in the search for excess weight, unproductive flab.

Flip up the sling rear seat to find a good-sized cargo hold. A version of the Carbon Cub SS SLSA is marketed as a single-place design to allow a higher empty weight, which in turn allows the use of larger tires for off-the-path flying.

All of this goes to work in the new Carbon Cub EX, an Experimental/Amateur-Built version of the SS that can, in fact, be built to a maximum gross weight greater than the LSA-mandated 1320 pounds (on wheels) or 1430 pounds (on floats). Testing on the structure has cleared many components to greater weights, but CubCrafters recommends a max gross of 1865 pounds for the homebuilt EX. Of course, any savings in empty weight forced by the LSA rules turns into pure useful load for the homebuilt. And while the push to reduce weight on the SLSA drove several design considerations, it’s all good for the version you can build.

How so? Let’s consider the reason for its name, Carbon Cub. Where the standard Cub or Super Cub’s steel-tube frame is a veritable maze of tubes and welded clusters, the SS and EX use a large carbon-fiber tub that forms the floorboards from the firewall to behind the rear seat. The pilot’s seat is part of this structure—underneath is a small battery, the ELT and other components that must be a first in packaging efficiency—as are other elements of the control system. While there are tubes beneath, the carbon tub allows consolidation of pieces and a massive reduction in the parts count. Cabin sidewalls and other interior pieces that are traditionally made of fabric in a Cub are also carbon fiber; recent updates leave the weave visible in the cockpit, under a shiny clearcoat, of course.

Heel brakes? Not here. Note the gel-coated carbon-fiber floor section that incorporates the rudder-pedal mounts, lower control-stick mounts and even the heater duct.

More carbon fiber? Sure. Elements of the regular Cub tail cone are designed simply to give the covering fabric its shape, so in place of several steel tubes are bows of lightweight carbon fiber. The wingtips are similarly simplified, with a combined tip bow and leading-edge D-section made out of carbon.

But wait, there’s more—actually, less. Richmond and his engineers took an extremely critical look at the wing structure and managed to remove a whopping 22 pounds per wing. How? Lightweight extruded-aluminum spars help, as do special two-piece stamped-aluminum ribs; they’re designed to fit around the main and aft spars, not slide over them as on a regular Cub. Overlapping tabs encircle both spars where the ribs meet them, and they’re glued together. This treatment simplifies buildup. Every fitting has been scrutinized to cut unnecessary weight. For example, where most Cubs have a single-thickness strap to act as a spar doubler/reinforcement where the inboard end is bolted to the fuselage cage, the Carbon Cub has a beautifully CNC-machined aluminum block whose thickness tapers the further it gets from the mounting bolt. What’s more, two of the four smaller bolts that secure the piece to the spar are used for the tank strap bracket as well; this is a separate part in other Cub forms. Long is the list of components that have fallen under the engineers’ unflinching gaze.

Upfront About It

What makes the Carbon Cub SS (SLSA) such a stunning performer—at least in every way but blazing cruise speed, and even then it’s not bad—is an almost overabundance of power. Most designs limited to the SLSA max weight have 100 to 120 horsepower to play with, and often have less than the EX’s 179 square feet of plain-flap wing as well. With 180 horses on hand, the EX bolts out the door and hammers uphill like a thoroughbred.

Vortex generators permit superb low-speed handling and reduce stall speed. They’re standard on the kit and the SLSA.

But we’re getting ahead of the pack here. Entry to the EX is typical Cub. Up over the tire, find a foothold on the landing gear, twist, turn, grunt, cuss and eventually find yourself seated behind a swoopy instrument panel. In the airplane I flew, a Garmin GPSMAP 696 was front and center, with analog and digital gauges sprinkled left and right. Builders have an option of a blank panel that comes with the kit, or any one of the prebuilt layouts as a no-cost option. That is, panels prepared for the production SLSA can be had, bare, at no additional cost.

Those of you averse to wiring can purchase turnkey panels across a wide range of prices. The base panel includes the primary instruments (no gyros) and a com radio; it lists for $8490. Add a Garmin GTX 327 transponder, Garmin GPSMAP 496 and a PS Engineering PM1200 intercom, and the package price is $15,190. Option packages up to $26,990 are available.

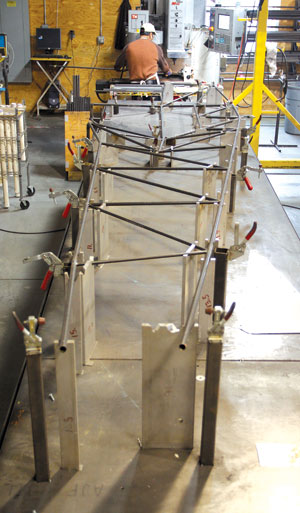

Fully jigged 4130 steel tube frames use CNC-cut ends to ensure accuracy and reduce weight and waste.

Whichever you choose, the core character of the Cub remains. You get your throttle on the left doorsill, with mixture and carb heat on the panel at the far left edge. Electrical switches are arrayed across the top, not in the wingroot. Dual toe brakes are standard, featuring lightened Grove wheels and brakes. Trim is electric; a small motor drives a conventional jackscrew, which adjusts the leading edge of the horizontal stabilizer. Flaps, unlike the PA-18’s, are easily adjusted without seeming as though you’d dropped your cell phone on the floor. A big handle above and to the left of your head moves the flaps through three extended positions; once you learn the trick to releasing pressure on the latch while in flight, they move easily and precisely. The fuel selector is at your left hip, while sight gauges are in the wingroots. The impression is of a tidy, utilitarian layout that’s still stylish.

No Time to Think

Startup is fuss-free, just like any carbureted engine. Dual LightSpeed electronic ignitions may improve hot starting, but our flight in a cold airplane during late winter in Yakima required a couple of throttle pumps and the slightest bit of finesse. (Electronic ignition supposedly increases power and efficiency, but it also allows for a significant weight reduction on the engine. Combined with a special intake manifold/oil sump, these mods take some 40 pounds off the firewall.)

A note about the performance. I flew with CubCrafters’ general manager Randy Lervold—himself a veteran builder—in a Carbon Cub SS right off the assembly line. The engine was still fresh, but more to the point of this story is that because it was an SLSA, we were limited to the 1320-pound max gross weight. With me and Lervold, plus half tanks (12 of the available 24 gallons), we were right at the maximum weight. Keep this in mind for the following breathless discussion about the airplane’s takeoff and climb performance. Should you elect to build your Carbon Cub EX at the highest 1865-pound gross, performance will not be quite as sprightly. Perhaps just merely flabbergasting.

That said…wow. I try to be a smooth, careful pilot, particularly in airplanes new to me. You won’t do that for long in the EX. The sequence is simple—power up, raise the tail, skim along for a bit, raise the nose and fly away. This entire process takes less time than most pilots need to shove the throttle fully open. To get the most out of this lightweight hot rod, it’s more like run the throttle briskly forward, count to about one, aggressively raise the tail, count to one, hoist the nose…and you’re gone. The EX leaves the ground behind almost angrily, and it honestly takes several departures before you catch up with the speed of the process and can begin to assess the subtleties of the airplane.

If you can manage it, try an initial climb with the airspeed needle stuck on 45 mph. The nose will be way up there, and the VSI will be pegged at better than 2000 fpm. All the while, there’s control authority to spare, no doubt in part due to the standard vortex generators, but your eyes and the seat of your pants are saying this kind of thing is suicide…no airplane climbs like this. Well, they’re wrong.

In flying patterns at the grass strip near CubCrafters’ Yakima home, we easily made pattern altitude by the end of the runway, and I soon learned to pull the power far back for the downwind leg. Flaps can come out at 82 mph IAS, and there’s the expected moderate pitch-up reaction when you tug on the lever. The flaps aren’t huge, but are reasonably effective; slipping is much better, and the Carbon Cub descends sideways so willingly that you’ll want to slip for every landing.

Hold 55 mph IAS down final, bleed the power off until the needle flickers below the 25-mph mark, and three-pointers are amazingly easy. While the brakes are powerful enough to put the airplane on its nose, the hydraulic relationships are spot on, so it’s easy to modulate them—not that you have to do much of that at such low landing speeds.

The Rest of the Time

You don’t buy an airplane just to perform landings—though this one you might—so we spent time exploring other areas of the EX’s expertise. Cruise speed is respectable for the type—115 mph TAS is a reasonable figure with the power way back and the fuel flow moderated to 6 gph. You can achieve 125 mph TAS, as we did at low altitude, but the fuel burn rises ruinously—expect to put 10 gph through the pipe at high power. With just 25 gallons on board, you will probably refrain. In fact, the EX is expressly happier at lower speeds and modest power settings, because the noise level goes down, fuel flow tapers toward the economical end of the scale, and efficiency goes up. Unless you’re trying to outrun weather, I can’t see why you’d use high cruise power settings.

Handling is marvelously Cub-like, heavier than you’d expect from a light airplane, but resolutely stable. Pitch-response tests show the airplane to return to trimmed airspeed quickly in two shallow phugoid cycles. The rudder is powerful, able to easily pick up a wing even from a 30° bank; however, you will get comfortable leading the turns with the rudder thanks to the EX’s pronounced adverse yaw. Just like a Cub, come to that. In every way that matters, the EX is a Cub, from the slightly drafty cockpit and the great view out under the wing to the stiffish gear and noticeable limberness of the wing in turbulence.

The CubCrafters facility in Yakima, Washington, is impressive, large and vertically integrated like you wouldn’t believe. On-site CNC machining and precision welding help keep quality up.

Here’s a sneak peek: CubCrafters was just beginning flight testing of a Baumann-shod amphib version.

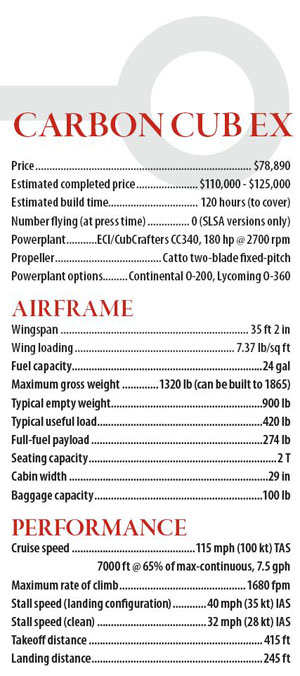

Bucks Up

Creating a Cub kit using almost jewel-like CNC-machined components and carbon fiber can’t be cheap, and it proves to be the case. The Carbon Cub EX kit is broken down into three major sections—wing, fuselage and finish kit (including all the covering materials)—for $21,660 each part. A firewall-forward kit runs an additional $8490. You can source your own engine, or purchase one from CubCrafters: The CC340 is $27,500, while a CC360 version is $29,500. You can also build for the Continental O-200, but as it’s just $5510 less than the CC340, your best bet is the bigger engine. Interior materials including seats and pads are part of the base kit, as are 6.00×6 tires.

Bottom line? All the major kits you’ll need minus engine, paint and avionics total nearly $80,000. If you shop from the catalog and buy a new engine, plan to spend anywhere from $110,000 to $125,000 for a completed aircraft. Consider as you work the figures that the SLSA version starts at $163,280, and you can’t have it at the higher gross weight or personalized in the same ways you could the homebuilt version.

Ultimately, CubCrafters will be happy to sell a comparative handful of kits as it turns out ready-to-fly examples, continues its restoration work on Piper-built Cubs, pushes Top Cubs out the door and develops neat accessories like amphibious float installation kits for the Carbon Cub. We like that kind of diversity in a kit company; it bodes well for its future. As for the Carbon Cub EX, it pretty much speaks for itself.

For more information, call 509/248-9491 or visit www.cubcrafters.com.