Light and ultralight aircraft offer a lot of great opportunities to the recreational flier that larger aircraft can’t. One of those areas may surprise you: It is the opportunity to set national and world records.

Everybody in the aviation world hears about it when someone such as Steve Fossett does something like becoming the first to go around the world in a hot air balloon. Of course being first is impressive, but any around-the-world record is also a speed record that can be broken by future pilots.

Going around the world in a general-aviation airplane is certainly an adventure. However, it has already been done many times before. It’s kind of like climbing Mt. Everest. Climbing that mountain may be a lifetime goal for you and a huge challenge, but you won’t find yourself in the news or the record books if you do it. However, it is still possible to set a record flying around the world in a GA airplane if you want to try it, but it is going to cost you some money and it will be very difficult to achieve your goal. Even more expensive records for GA-class aircraft would be any speed, time-to-climb or altitude record. Most of it has been done before, and to do it better, you will have to invest a significant amount of cash.

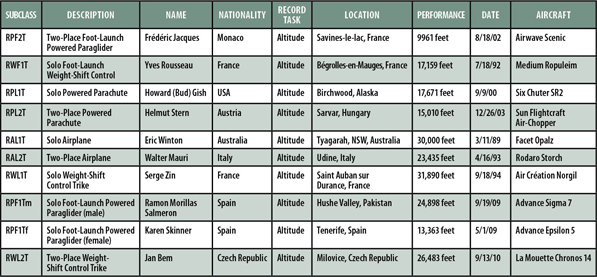

Microlight altitude records are only part of the record-making opportunities for ultralight and Light Sport aircraft.

Leisure Time

Greener pastures for aviation record setting can certainly be found in the microlight world because there is a wide variety of aircraft types and possible records.

Last year Norman Surplus began a journey from Ireland to attempt to become the first gyroplane to fly around the world. The trip ended in difficulties, and the record is still open.

First, you have to realize the difference between microlights and ultralights. The world authority for aviation records and contests is the Fdration Aronautique Internationale or FAI. Fortunately, despite the French name and the Swiss headquarters, the FAI prepares all of its rules and documentation in English. Unfortunately, it is very British English, including the name of the category for most of the records ultralight and Light Sport pilots would be interested in. The name is “microlight.” Now microlight has always seemed to me to imply aircraft even smaller than ultralights. Instead, microlight is a category of aircraft that includes all powered ultralights and many Light Sport aircraft. The category is mostly defined by the gross weight of the aircraft. Those gross weights are divided into single versus two-up loaded ships as well as land versus seaplanes. The maximum takeoff weights are:

- 300 kilograms (661 pounds) for a landplane flown sol

- 330 kilograms (728 pounds) for an amphibian or a pure seaplane flown solo

- 450 kilograms (992 pounds) for a landplane flown with two persons

- 495 kilograms (1091 pounds) for an amphibian or a pure seaplane flown with two persons.

It does not matter whether the aircraft are foot-launch for the weight requirements. Currently microlights include all types of aircraft normally considered sport aircraft except for gyroplanes, which are covered along with helicopters in the Rotorcraft Commission. Still, an amazing array of aircraft and powerplant records is possible. Microlight aircraft records are classified by type of control system (aerodynamic control, weight-shift control or paraglider control), type of landing gear (land, sea, amphibian or foot-launched), number of people on board (one or two), power source (thermal or electric engine) and even in some cases whether the pilot is male or female (foot-launch powered paragliders only). Currently that adds up to 29 possible categories of aircraft you can begin to compete in! (OK, only 28 possibilities if you aren’t willing to go through the sex-change operation.) And to think, we haven’t even begun to talk about the possible records that can be established or broken in each of those categories.

The types of records can basically be broken down into speed, distance, altitude and time to climb. But even with those basic categories, the rules spell out the following categories for microlight records:

- Distance in a straight line without landing

- Distance in a straight line without engine power

- Distance in a straight line with limited fuel

- Distance in a closed circuit without landing

- Distance in a closed circuit without engine power

- Distance in a closed circuit with limited fuel

- Altitude

- Time to climb to a height of 3000 meters

- Time to climb to a height of 6000 meters

- Speed over a straight course

- Speed over a closed circuit.

That returns a possibility of 28 x 11 or 308 possible records. But as they say, “Wait, that’s not all!” For example, speed over a straight course can be done between any two points in any category of aircraft. Now to be sure, there are some limitations. For example, a record flight between St. Louis and Chicago is not an international record; it is a national record. Which brings us to another great point.

Dean Eldridge traveled from the UK to set a speed record in a powered paraglider this winter. Here he can be seen preparing his ballast for the record-making flight, spent bullets from Arizona.

In Your Own Hometown

Even if you don’t want to try for a world record, you can try for a national record. If nothing else, that can be something of a nice consolation prize if you try for a world record and don’t quite make it. What a deal! Consolation prizes in the records world aren’t offered that often.

But the larger point is that there are literally thousands of possible records that can be set or broken. And you might be surprised to find out that a lot of records haven’t been set yet. The largest example is all of the electrically powered aircraft categories. Electric aircraft haven’t been on the scene long, and the rules allowing for the setting of their aircraft records haven’t existed long. When those record categories were established, that almost doubled the number of potential microlight records that could be set. And there aren’t that many people out there attempting these records.

Are You Up for It?

So what does it take to set a record? First, you need to find and read the instructions. Those are available online at www.fai.org in the documents section. If you fly microlights, you want to refer to Section 10 of FAI’s Sporting Code. You rotorcraft types need to download Section 9 of the Sporting Code.

It also would be a good idea to visit the world records section to see what kind of world records have already been set for your category of aircraft. If a record hasn’t been set in an area you are interested in, you have found a great target of opportunity. That is a situation where you will only be competing with yourself to set an initial record that is respectable enough that no one will want to try to challenge it right away. But even if you don’t do an incredible job, you will still set the world record. Not a bad little goal for the flying season!

If a record has already been set that you would like to break, the next step would be to make a dry run to see if you can best the record. You don’t need special recording equipment to do this because you are just trying to get a rough estimate of your chances of breaking the old record. You may find that you need to upgrade equipment, lose weight, recruit a lighter copilot, find better atmospheric conditions to make the attempt or all of the above. But that bit of research into you and your aircraft’s capabilities is an important part of the process.

Somewhere along the line you are going to need to talk to the National Aeronautic Association (NAA), which is the USA’s National Aero Club that works with the FAI to certify world records. Their web site is www.naa.aero.

Gearing Up

By reading Section 9 or Section 10 of the Sporting Code, you will discover the requirements for observers and special recording equipment. Observers may have to be dedicated to your record attempt. They cannot be just random people you find at the airport. They need to be approved by the NAA and the United States Ultralight Association (USUA) and they must be trained to do the job. There are certain tasks that an observer has to perform. If those tasks aren’t performed properly, it can put your entire record attempt at risk.

A Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) recorder will be a critical piece of equipment for speed and distance records, and it must have a pressure sensing device to authenticate time-to-climb and altitude records. It is important that neither device be tampered with during the flight.

Finally, there is the paperwork. And this is what assures that you have a real record and not just a you should have been there experience. You need to be a member of USUA and NAA as well as have a sporting license. For many records you also have to declare what you are going to do before you do it. Normally you are given a set window of time to accomplish the record.

All in all, it takes more than piloting skill to establish a world record. It also takes the right aircraft, planning skills and coordination to make it happen. But once it does happen, you have secured a small piece of aviation history as your own. And it makes for another great flying experience.