Independence Airpark, Oregon, lives up to its name, seemingly encouraging a level of aeronautical creativity free of preconceived notions. Experimental Aircraft Chapter 292, based on the field, has added to the innovative spirit, with everything from ultralights, to the group production of 14 Nieuport fighter replicas, to a human-powered airplane. Among the members is Robin Reid, one of the pilots on the first-place Green Flight Challenge Pipistrel G4, an electric airplane of refined performance.

The Nieuports project became a touchstone for Chapter 292, garnering massive publicity in the aviation press. The proven design, built of gusseted aluminum tubing and requiring no welding, lent itself well to a group project. The final lineup of aircraft astonished one and all. No participant actually built any one airplane, but the team built all 14 together, with a drawing held to determine who got which finished product. Thirteen team members ended up with an airplane each, and the extra was auctioned off to provide funds for the chapter. Builders customized their aircraft with paint jobs that included an N number and personal identification, most of which honored individuals or flying groups from the “Great War,” with the possible exception of one that sported Betty Boop as its mascot.

Bruce Rose attaches the compression strut, threading the mounting bolt through an intricate series of jig and structural holes.

The group called itself The Noon Patrol because, as they explained, “The Dawn Patrol name was already taken, dawn is too damn early anyway, and we fly for food.”

Today, only one member of that group still owns his original aircraft. All but one Nieuport, reputed to be hanging in a Salem, Oregon, area furniture store, are flying with new pilots.

That rigorous repetition of wingribs, fuselage formers, struts, wires and the heady fumes of Polytak must have instilled a positive reinforcement in the brains of at least five chapter members, because they are in the midst of repeating that grand experience on a larger aircraft: the de Havilland-designed Airco DH.2, a WW-I gunbus that dwarfs the diminutive French fighters.

Gary McCormick mounts the “birdhouse” to the wing. The structure provides stiffening against fabric shrinkage. Twenty of these were fabricated, one for each wing.

The DH.2 is an aerial vehicle of formidable size, standing more than 9.5 feet tall, with a wingspan of 28 feet and a length of 25 feet (about 7⁄8 the size of a Stearman, according to Bruce Rose). Its gross weight was a feathery 1441 pounds, according to the Great War Flying Museum in Ontario, Canada. Its Monosoupape or Le Rhone nine-cylinder rotary engine twirled in a birdcage of struts and wires behind the pilot, allowing its single Lewis gun, mounted in the nose, to be fired without fear of striking an errant propeller blade. Early in the war it was credited with ending the “Fokker scourge,” the threat of the deadly little E1 Eindecker that Max Immelmann had made famous for its lethal maneuverability and forward-firing machine guns.

Bill Osborn sets up the jig for the tailbooms.

Part of the charm of the DH.2 is its unique configuration and a reputation for being docile enough for amateur pilots. It looks deceptively simple to build, with identical top and bottom wing panels and open rear fuselage construction. Ernie Moreno promised, “We are not building flying coffins,” underscoring the seriousness of the enterprise and the desire to have a fulfilling and affirmative experience.

The landing gear with Harley wheels and O’Brien brakes.

Taking a slightly different approach from that used by the Nieuport team, each DH.2 builder is constructing his own aircraft while sharing tools, ideas and some of the repetitious component manufacturing.

Assembling the team was as important as assembling the airplanes. A diverse ensemble of retired professionals with varied backgrounds, each member of the team complements the others’ skills and interests in a highly synergistic way. Moreno, for instance, has a Pietenpol, Weedhopper Gypsy, Sorrel Guppy and an Aeronca C-2-like Independence Flyer to his credit. His demonstrated building credentials and years of experience lend much authority to his understanding of how airplanes should go together. Gary McCormick, a retired Intel engineer, designs required pieces with precision to the thousandth of an inch and creates items such as control horns that look like the original while embodying best current practices. Bruce Rose, a former electronics engineer for Tektronix and Intel, brings an understanding of the design process and keen interest in airplanes. Paul Sieber, a dentist, rivals his fellow builders’ perfectionism in crafting the often-ingenious structures. Mike Pongracz, a retired business owner, brings his business experience to keeping records and finances in order.

The forward fuselage with wing center struts. Note the multiple fittings needed to hold it all together.

Pongracz and Sieber were part of the Nieuport experience, but the rest of the team is beginning this build with other previous projects in their resumes, and all are committed to a high level of craftsmanship and professionalism in their work.

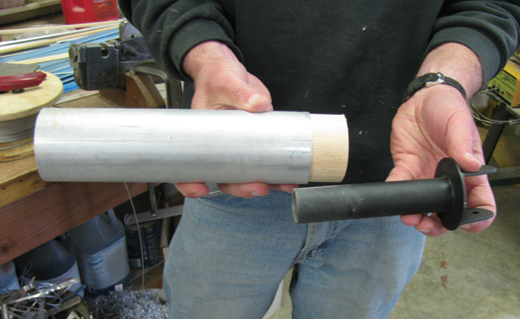

The compression tube is mounted in place with drag wire fittings.

Lucky to be based on a thriving airpark, with homebuilt and restored treasures hidden in hangars along the multiple taxiways, the core building team is also supported by a community of resources, without which, Rose points out, this project would not be possible. Chapter 292 has a wealth of materials, skills and expertise to share, including tools and a wood shop. People like Bill Osborn drop by to provide help such as triangulating the angles and setting up the jigs that will allow the tailbooms to come together. This unique environment helps the builders flourish, as shown by the annual “Taxiway of Dreams” celebration, which allows all to share their varied creations.

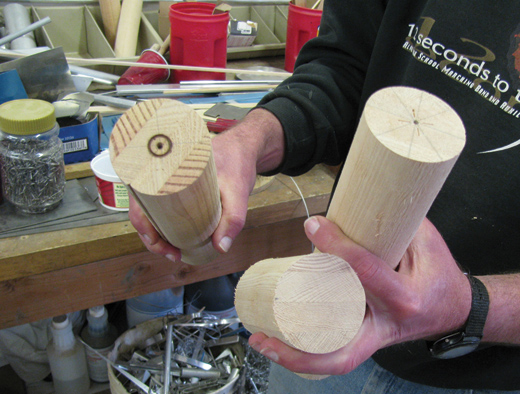

Rose shows the laminated dowels used to connect the wingspars to the wing mounts.

While the Nieuport had the benefit of plans and well-documented building practices, the current project relies on a reverse engineering process that also requires creating new manufacturing techniques. These give not only the form of the original, but the necessary strength to ensure safe flight. Working only from a series of scaled general arrangement drawings, the team had to create an airplane that used more modern materials and would reflect current best practices wherever possible. Evidence of that is the claim that empty weight for the replica will be half that of the already-light original. With roughly the same power as the original from its Volkswagen engine conversion, takeoff and climb should be positively levitating.

Having conceived this latest project in May 2010, the DH.2 team is making great progress. With tail feathers completed by Independence Day (in Independence no less!) 2010, the group evolved pieces as they carefully thought through each segment of construction. They design each component to fit what has been created already, and plan carefully to make sure the new parts come together as though they had been crafted for that purpose from the beginning.

This is how the tube, dowel and folding wing mount go together.

What would otherwise appear to be “on-the-fly” design and construction relies on careful research and the experience and thoughtful input of the builders.

Numbers tell some of the story. Pongracz routed 6000 feet of capstrips, for instance, causing some hearing loss for all and making the gang look forward to some quiet gluing. Each of the 300 54-inch chord wingribs is routed from 4-millimeter aircraft plywood (more than 24 sheets at $65 each), and is stiffened with American-made tongue depressors. The toughness of this unique material is a bit astonishing, emulating the strength and stiffness of composite construction sandwiches, but with more traditional materials. It took a lot of time rummaging through local drugstore supplies to find domestic depressors, because many medical supplies today come from far offshore.

Rose holds the aileron mounting blocks.

The center section and fuselage have to be aligned and measured with great precision, as upper and lower wings, landing gear and tail structure all have to connect neatly through and around this core element. One cluster of structures coming together in the lower part of the forward fuselage requires the drilling of 37 holes, each pointing in a different direction and angle—definitely not something to be tossed off lightly “on the fly.”

As reported in the building log on Chapter 292’s web site last November, “The landing gear has been finalized and nearly all of the components’ attach fittings. The center section incorporates all the attach fittings for the wings. The precision with which the pieces are coming together is a testament to the detailed planning of Ernie and Gary. It’s a beautiful thing!”

Progress continues, because the group is fairly intense and totally dedicated to achieving its goals. They don’t mind visitors, but request that people tend to their own self-created, self-guided tours, allowing progress to continue. They don’t even want to socially network about the project at this point. The Nieuport team was inundated with enthusiasts and curiosity seekers, probably delaying completion by months and often frustrating the builders.

The “Independence Five” don’t plan to formalize anything, and will not offer plans or building assistance. There are a few builders in New Zealand who went through a similar reverse-engineering process. Maybe they’re willing to give up nights and weekends answering fan mail and myriad questions, but this group wants to be independent of that responsibility.

They will gladly point out that, though these flying machines radiate a positively romantic glow, and bespeak some long-lost chivalrous age of knightly combat in the air, they require care even by an experienced pilot and fly much differently from the modern Cessnas and Pipers we are used to. The historic texts Bruce Rose shared with me provide a series of pictures in which the DH.2 is nose down or inverted following a bad landing. Training accidents in both WW-I and WW-II were as costly to allied airmen as actual combat.

Tail feathers adorn the walls of the shop.

Commodore Allen Wheeler, one of the founders of the Shuttleworth Trust in England, spelled out the difficulties of handling early flying machines in his book on building airplanes for the movie, Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines. Although the film was set in 1910, the technology had not advanced that much by 1915, and according to Wheeler, did not reach the handling characteristics of “modern” aircraft until around 1926. Think of how quickly a Piper Cub or Aeronca Champ slows down after one chops the throttle. Now imagine the Cub or Champ as a biplane, with a totally unstreamlined fuselage. Cutting the throttle in such a machine brings about rapid deceleration, as quickly as the airplane’s drag catches up with the missing thrust, which in a WW-I machine like the DH.2 was equal to the meager power necessary to allow not-too-radical flight maneuvers. One has to drop the nose quickly or face an inevitable stall and recovery.

Each member of this building group is an aviation historian, with experience in a variety of craft, and accept that their DH.2s will have only 4 pounds per square foot wing loading, somewhere in ultralight territory. They also accept the fact that trips to the Arlington Fly-In, less than 250 miles north, may take two days in each direction, with only early morning and early evening excursions in the still air desirable. Tossing in a day at the airshow, a five-day excursion will require some careful planning and meteorological luck. After all, these are truly open-cockpit machines that are likely to fill up while flying through, or parked under, a downpour—not exactly a remote possibility in the Pacific Northwest.

Obviously, despite the high coolness factor and the romance associated with what in reality was an achingly dirty job, the DH.2 is not for everyone, and it’s probably the desire to avoid the pain of finding that the plane of your dreams is a harpy in disguise that motivates these stalwart builders. They have your well-being and peace of mind foremost.

In the meantime, we’ll follow their progress and share the clever solutions and approaches the group finds during its journey to project completion. You can also read about their adventure in the EAA Chapter 292 on-line newsletter (www.eaa292.org).

![]()

Dean Sigler has been a technical writer for30 years, with a liberal arts background and a Master’s degree in education. He writes the CAFE Foundation blog andhas spoken at the last two Electric Aircraft Symposia and at two Experimental Soaring Association workshops. Part of the Perlan Project, he is a private pilot, and hopes to get a sailplane rating soon.