Fun and fantasies: These are the two main ingredients that the three-quarter-scale Grass Strip Aviation Ltd. (GSAL) Fokker E.III Eindecker ultralight dishes up by the plate load. Known as the “Scourge” for a while in 1915 and 1916 by Allied pilots, the WW-I Fokker Eindecker (translation: “monoplane” or “one wing”) ruled the skies of the Western Front. Now pilots can rule their own skies in this delightful FAR Part 103-compliant sub-250-pound (115-kilogram) ultralight.

A fair-weather, single-seat aircraft, it offers a great way for a bunch of friends to enjoy the benefits of unrestricted flying that Part 103 presents. The three buddies I met recently in rural Gloucestershire, England, are Robin Morton, George Simoni and Shaun Davis, respectively a retired airliner flight-test engineer, automotive project engineer and restaurateur. All are experienced and enthusiastic ultralight (microlight in the U.K.) pilots with a penchant for classic and vintage ultralights. They fly together at the same club, and, as often happens in drink-fueled discussions, one evening after a meal together they were listing the favorite aircraft types they’d like to build. Miraculously and independently, all three said the Fokker Eindecker, and there was no turning back. They researched available kits, found Airdrome Aeroplanes in Missouri and were soon talking on the phone with Robert Baslee, the company’s founder, in Holden, Missouri.

Regulatory Hurdles

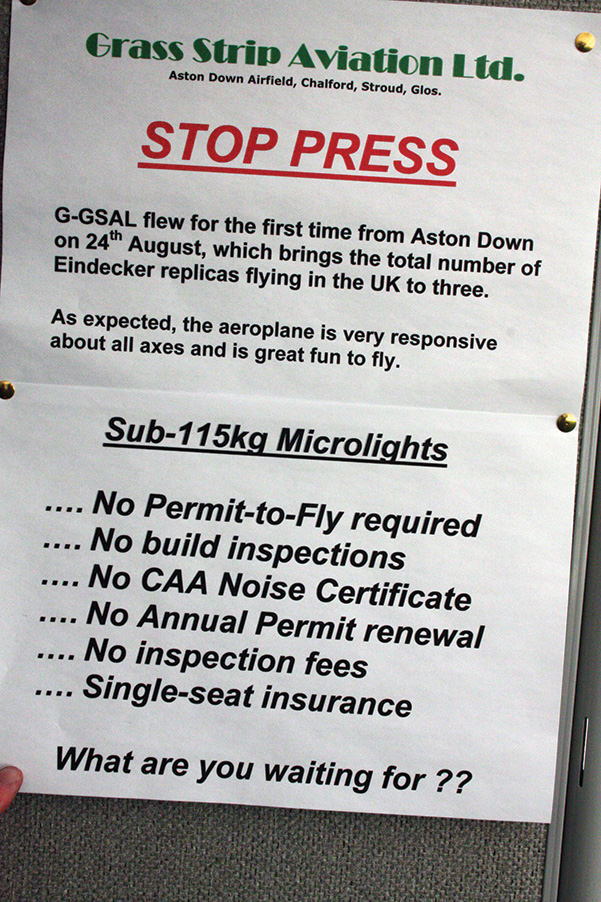

Airdrome Aeroplanes has been selling its WW-I replica kits for more than 10 years and now has more than 20 kit designs, the Fokker E.III Eindecker being one of them and one of the few in the catalog that is Part 103 compliant. The Eindecker also has a modern GA wing profile with ailerons and not the wing warping of the original design. The first problem in the international mish-mash of aeronautical legislation was how a Part 103 legal ultralight could be built and flown in England. Here, the rules are much more rigid and stringent. There are the BCAR Section S—Microlights, which require a major certification effort with the authorities, cost- and time-wise, out of all proportion for a trio of amateur pilots who just want to build and fly a fun kit aircraft.

Morton, accustomed to the traumas of flight-test bureaucracy, set out to find a way ahead. Then in 2007, like the Red Sea parting for Moses, the way appeared: The U.K.’s Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) introduced the Second Amendment to the Air Navigation Order, addressing the “Airworthiness Deregulation of Small Microlights,” amending Article 8(2) of this legislation to cover sub-250-pound (115-kilogram) microlights. In essence, it states that any aircraft that has a single seat, weighs 250 pounds or less without pilot or fuel, and has a maximum empty weight wing-loading of 22 pounds (10 kilograms) per 10.76 square feet (1 square meter), is allowed to fly in the U.K. without formally showing compliance with any airworthiness regulations. Quite liberally, though, it is hoped that the aircraft in question will satisfy the broad requirements of BCAR Section S—Microlights. Another advantage of operating such an aircraft in the U.K. is that the pilot need have only an NPPL (M) (National Private Pilot’s License (Microlights), which requires a driver’s medical to be valid). The aircraft requires no build inspections, there’s no annual permit or noise certificate, and only single-seat insurance is needed. The aircraft does have to be registered with the CAA. Build a conventional Experimental kit in the U.K. and the CAA (via the Light Aircraft Association/LAA) will want to know about it, and it does not particularly like the tube and riveted-gusset type of construction used in the Airdrome Aeroplanes airframe.

Free Agency

With the road ahead now reasonably clear, the trio of friends approached Baslee with the intention of buying one of his Fokker E.III Eindeckers each. Baslee said, “If you buy four kits, you can become a U.K. agent.” So that is what they did, establishing Grass Strip Aviation Ltd.

GSAL is more than just an agent, though, and the principals bring many decades of experience as pilots and in aerospace manufacturing, servicing, certification and flight testing to the new company. With the liberal sub-115-kilogram approvals comes responsibility, combined with GSAL’s desire to improve and perfect the design for European operation while also building a reputation for integrity. The aim is to import other aircraft from Airdrome Aeroplanes, and they would like to add a Sopwith Pup or other biplane to inventory. They also want the builders of the kits they supply to have a good and pleasurable experience, so they set about analyzing the Eindecker design, drawings and kit.

Improving on a Good Thing

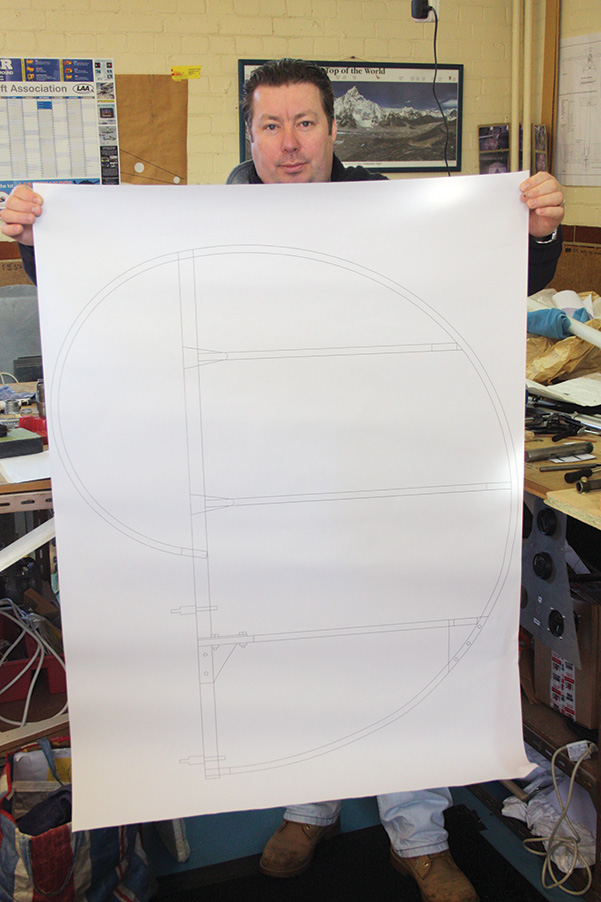

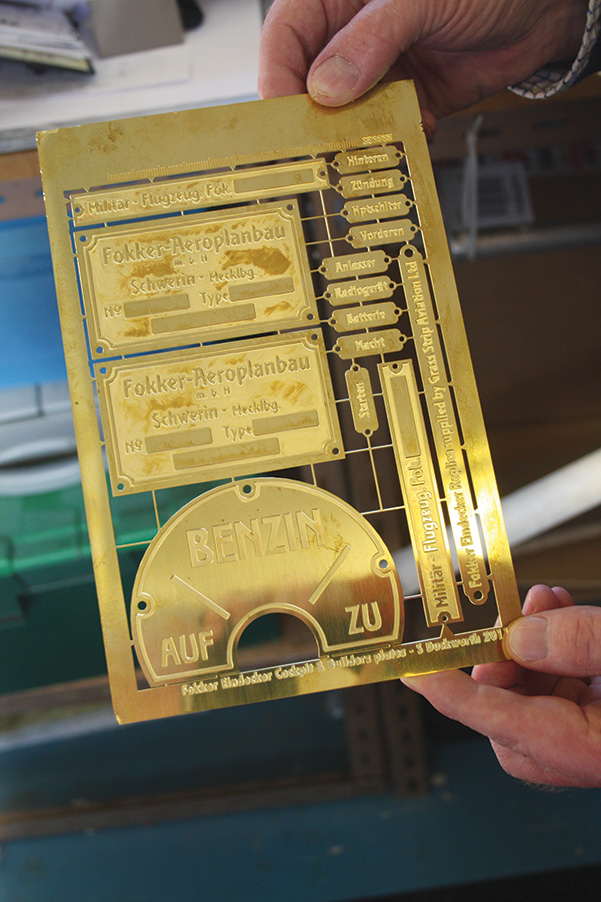

The first task they undertook was to catalog the drawings, number them and then produce CAD 100% versions of them so that the builder can lay out the drawing and components on a flat workbench and build as one would a model kit. The only drawing they haven’t converted, solely because of its size, is the wing. They have also produced a comprehensive build manual, a DVD of construction techniques and a DVD of still photos of different parts of the structure.

At an early stage, a potential customer might have been surprised that Airdrome supplied 500 feet of straight aluminum tube, which the builder had to bend and cut. GSAL now cuts and bends all tubing, plus all sheet aluminum, to shape, but the wing and flying surface ribs come as flat alloy and need two 90 bends, top and bottom. After building and flying their prototype, many idiosyncrasies in the original came to light, the first the buffet to the control/joy stick the pilots experienced. The Airdrome design has full-span ailerons, and the wash from the propeller was producing dirty airflow over the inboard section of the ailerons. They modified the ailerons to 50% of the span and the buffeting stopped, so this is now standard in the company’s kits. Landing and ground handling also received much attention, and because they wanted to fly from hard runways, they introduced an undercarriage compression-spring modification and, using a tailwheel (rather than a skid), a tailwheel suspension mod. For ease of storage and transport, GSAL has also designed an aileron quick-disconnect (de-rig) mod and is working on a folding-wing option. The Airdrome Eindecker has eight wing-bracing wires, but the original had 16; GSAL favored the original design, so this is what the kit customer gets, along with the necessary turnbuckle set for adjusting tension. The company is also looking at weight-saving aspects of the design and is fitting calliper mainwheel brakes taken from a quad bike and operated from a lever in the cockpit to improve ground handling and offer better control at start-up without chocks. The whole brake system will add no more than 2.2 pounds (1 kilogram) to the empty weight.

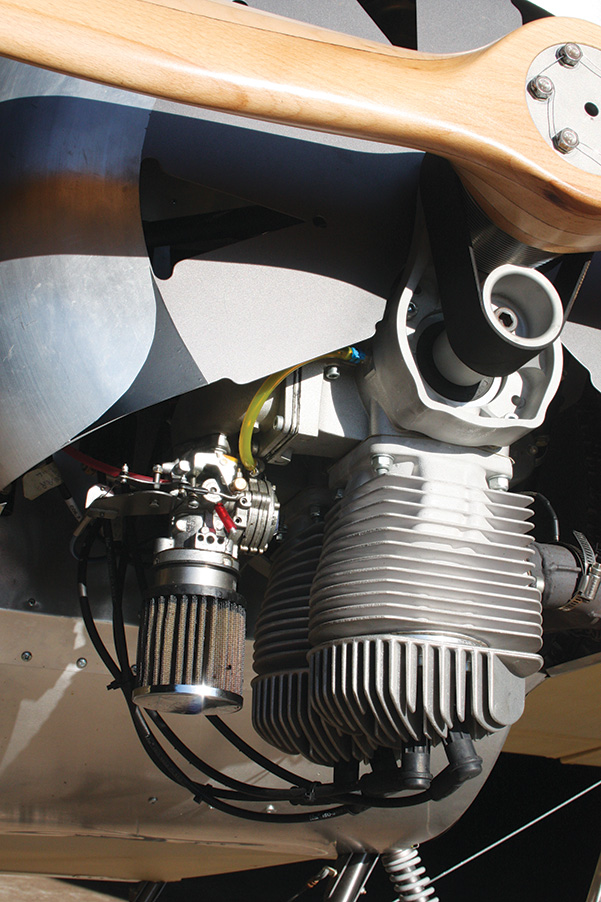

Mating Engine and Prop

GSAL’s prototype is now flying with a Canadian 45-horsepower CRE MZ-201 in-line, two-stroke engine, which the company now considers optimal for the design. The engine and propeller combination has taken the most time and effort to perfect. Various other engines have been fitted or suggested, the Rotax 447, the single-cylinder 28-hp CRE MZ-34, the Briggs & Stratton V12, Solo 35/40 and the Fuji Robin. With a modified exhaust that twists up under the nose bowl/cowling and back down again, the CRE MZ-201 remains the choice. Designed in Italy by Michael Zanzoterra, where the block is still cast, it is now built by Leon Master’s Compact Radial Engines (CRE) in Surrey, British Columbia, and meets the GSAL requirement for electric starting. The only box it doesn’t tick is that it is still a two-stroke, which requires the “dark art” of oil-fuel mixing prior to operations. However, producing 45 hp at maximum 4700 rpm, with two cylinders and in-line, dual CDI ignition, belt reduction drive, carburetor and exhaust, it has proved to be suitable for the job. The two-blade prop to match has swung between a Culver 64×33 and the U.K.-built Hercules. The advantage of the Hercules is that manufacturer Rupert Wasey is just down the hill from GSAL’s Aston Down airfield base. They hoped with a smaller prop to reduce fuel consumption from the 5 gallon (20-liter) tankage. A 62×36 propeller proved too small because the nose bowl/cowling reduced its efficiency. All recent test flying has been with the Hercules 72×35, plus a grooved belt 2.08:1 reduction drive, and with this, GSAL has found the right formula.

Cold-Weather Flying

At the time of my visit, the company was finalizing the test flying of the Fokker Eindecker with the MZ-201 and Hercules 72×35 wood prop. Morton, suited and booted in his winter flying gear, wanted to further test this engine/prop combination in climb tests and to open up the flight-test envelope with steep turns, stalls and general handling. He had an independent ASI and altimeter hung on a belt around his neck, plus stopwatches and a note pad for his time-to-climb tests, a lot of paraphernalia for a small, open-cockpit aircraft. He seemed to be enjoying it too much, and I was worried he might freeze if he stayed airborne for too long. I was also eager for him to land so that I could have a brief flight.

The modified, and sturdy, main undercarriage. This coil-spring option replaces the Airdrome Aeroplanes bungee suspension.

The easterly wind was less than 10 knots but straight down the hard runway. The maximum takeoff weight is 500 pounds (230 kilograms), so with about 3.5 gallons (13 liters) of fuel and my 170-pound weight, plus instruments, the Fokker Eindecker was close to MAUW. The mission preflighting concluded with clipping the mock Spandau machine gun onto the top of the cowling (though being detachable, this isn’t included in the empty weight calculation). I had to get kitted with a windproof one-piece suit, boots, leather flying jacket, leather helmet and goggles, as the temperature was just above freezing.

Cockpit entry is not dignified but totally authentic—what those WW-I aces had to do! A detachable aluminium folding ladder is attached to the rear spar, so I clambered up, scrambled along the top of the fuselage and then, with hands on the cockpit longerons, slid down into the 22-inch-wide, spacious cockpit. (The ground crew removed the ladder.) There is no seat or rudder-pedal adjustment, so with cushions beneath and behind me, I got comfortable before doing up the four-point harness. The controls are all standard, with stick and rudder pedals, the throttle on the left-hand side of the cockpit. They seemed to come comfortably to hand and foot, and when I waggled them during the preflight checks I noted they had well-engineered stops.

Despite the deliberate WW-I look of the Eindecker, this is one modern ultralight thanks to the MZ-201 and its electric start. Settled and briefed, I made sure the ground crew had the wheel chocks in place, and then primed the engine with the lightweight, chain-saw-type push button. I flicked the Master switch and ignition switch to “On,” and after bellowing, “Clear prop,” set the throttle; with the lightest touch on the starter button, the prop started spinning and the engine fired immediately. There is no choke, so I gave the engine a couple of squirts on the primer so that it settled down to a smooth tick-over at 2200 rpm.

I had been warned to take great care while taxiing because no brakes had been fitted to this Eindecker as yet, due to the weight constraints of the prototype. With the chocks removed, I was on my own, so with deft use of the throttle and rudder pedals, I cautiously edged forward on the grass, heading for the back track on the hard runway. The ground handling is precise with the spring-loaded tailwheel steering, and the ride over the grass was remarkably smooth thanks to the GSAL-designed, coil-spring main undercarriage legs. The view over the nose while taxiing is good for a taildragger, even with the birdcage illusion of cabane strut and flying wires interrupting the view. As much to feel the handling as to get a better view, I weaved the Eindecker during taxi to the hold in preparation for takeoff. I also gunned the throttle during taxi, once I was happy about the handling, to ensure no engine cooling.

A Quick Sample Flight

The moment arrived, and with a call on the handheld radio to warn any other traffic about my impending takeoff, I lined up into the wind, did a final visual check inside and out, slowly advanced the throttle, watched the rpm increase and kept my feet on the rudder pedals. I found it easy to keep the Eindecker straight with little “pedaling” and raised the tail. At about 40 mph indicated, I was flying in a takeoff distance of about 300 feet, the forward view over the nose good as I realize that I’m sitting relatively high in the cockpit. The engine rpm is 4500, and I establish the suggested climb speed at a steady 45 mph. The positive feel of the controls is typical of a standard three-axis ultralight, with pitch and yaw being sensitive, yet roll a bit heavy. Continuing the climb at an impressive 600 fpm, I take the opportunity to start looking around, the wind in the wires, the long wings and those sinister black crosses near the wingtips. Then I see the Spandau LMG 08/15 machine gun on the cowling, and it’s almost impossible not to be thrown back in time nearly a century and keep a wary eye out for those marauding Allied aircraft, glad that the gun is loaded and ready for action!

Established at 2000 feet, it is darn cold despite the winter sunshine. I throttle back to about 4000 rpm for some straight and level, the ASI showing 51 mph, before starting to explore more of the Eindecker’s handling characteristics as quickly as I can because I’ve got to be back on the ground soon. Yes, the roll is heavy, partly, I’m told, because of the static friction inherent in the Teleflex cables that operate the ailerons. I try a medium turn of about 25 of bank to both the left and the right with the aircraft generally behaving well, though with rudder input I find the reaction quite dramatic; obviously to fly a balanced 360 turn is going to take more practice than I have time for today. I try an even steeper turn, between 45 and 60, and really begin to feel I am the fighter ace. Recovery to straight and level is almost instant with combined use of ailerons and rudder. To sample the Eindecker’s stall I ease off the throttle and watch the ASI decrease, until at 31 mph IAS there is an initial “nodding” and sloppiness in the stick, the full stall coming at 29 mph IAS with a slight right wing drop as the nose goes down, but rather benign. To recover, I centralize the stick and apply power, and in an instant am back straight and level.

Heading Back

All too soon, it is time to go home, though at all times I’ve been visual with the airfield. I make a safety call on the radio about my intention to land, and ease off the power to descend back into the pattern. As I close the throttle, the nose drops significantly and I glide down at 45 mph with an excellent forward view, reassuring for the final approach. I make a large, gently sweeping turn to get lined up with Aston Down’s long, hard runway (the Red Arrows used to fly from here back in the 1970s) and ease off the power. I was expecting to have to fly a curved approach, but as I found in the descent to the pattern, the forward visibility continues to be good, and I am blessed with a slight breeze straight down the runway. I do a wheel landing, the best on a hard runway, though three-pointers may be preferred on grass/turf, chopping the power once I feel the rumble of the tires, all the time sensing that the Eindecker is trying to skittishly get away from me, so I keep pedaling the rudder to keep straight. The slightest gust of wind could get under those big wings and spoil my day. I stop in about 600 feet and then gently apply throttle to taxi to the waiting ground team. I can feel that smug smile of satisfaction spreading across my face, as yet unseen by the ground crew because of my helmet and goggles. I hadn’t realized how cold I was, so with the airplane safely hangared, we retire to the workshop for some hot tea and cookies, and a debrief.

Postflight

The GSAL Fokker E.III Eindecker is a pleasure to fly, though it would be nice to have some form of in-flight pitch trim to ease the flying load on longer trips. I estimate that I burned about 2 gallons (8 liters) per hour on my short flight, which isn’t going to damage the bank balance too much. A better radio antenna would also be advantageous for the handheld, particularly with busy air traffic, and the intention of GSAL to fit caliper brakes will be a bonus to ground handling. This is also a test airplane, so the cockpit is a little cluttered and could be made more authentic. In fact, for the type of flying it does, if you are in the outback, you could dispense with a handheld radio altogether. The airplane compares favorably with other very light single-seaters I’ve flown, and will likely give the average taildragger pilot few scary moments as long as he is always mindful of just how light it really is.

This Eindecker is also quick to build, 15 months being the estimate for an average novice builder. No woodwork or fiberglassing is required, and it can be built in a standard-size garage of about 20×8 feet. Then you can launch into the air and fantasize about dog-fighting WW-I style, flying the Scourge of the Allies, who hadn’t worked out how the enemy was able to attack them from behind and head on. It was the clever repeater gear and bullet deflectors that enabled the Spandau machine gun to fire forward through the blades of the rotating prop, but that’s another story.

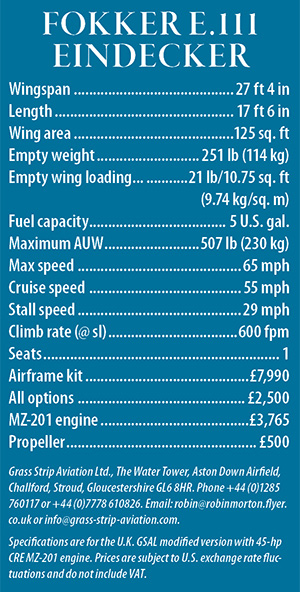

For more information on GSAL, visit www.grass-strip-aviation.com. In the U.S., call Airdrome Aeroplanes at 816/230-8585, or visit www.airdromeaeroplanes.com.