Building an airplane, and getting it to fly, is a technical activity. It requires a great deal of “left brain” thinking, intellectual analysis and concrete decision-making. Deciding how your airplane should look, well, that’s another matter. When it comes to paint schemes, the right brain has to get involved: The artistic side of the builder must be acknowledged (even if it is eventually ignored), and the imagination must be allowed to come out. There are as many ideas about how an airplane should look as there are builders and pilots—perhaps more—and paint schemes vary across the spectrum. Traditional colors and stripes, military look-alikes and polished aluminum with trim share the skies with everything from unpainted airframes to the wildest artistic impressions. There is no right or wrong in the world of paint schemes, because in the end, the look of an airplane is art, and as the old saying goes, art is in the eye of the beholder.

This article is really about creating art: the approach we took in turning a brand new, bare-metal homebuilt into something exotic. It should give you an idea of the process involved in conceiving, planning and executing a project to create something wild. This is not an article on painting an airplane so much as it is about executing a concept. A wild paint scheme is not for everyone, and in fact may be a course chosen by only a few. After we go through the process, which in our case took more than a year and a half, it might well discourage even the heartiest of souls.

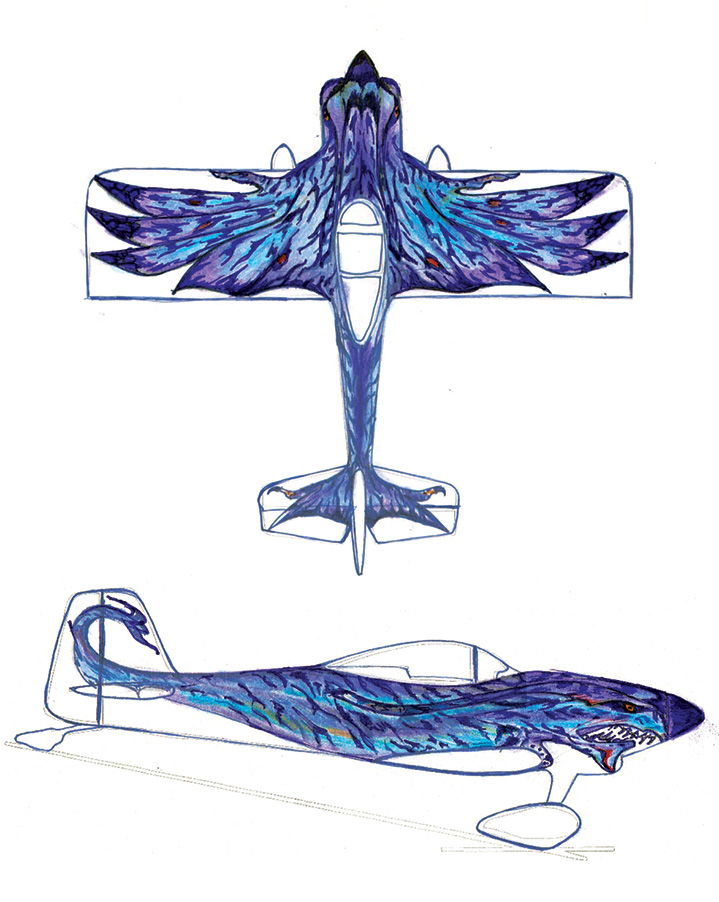

The concept model developed by Gary Zahradka was used to determine that the airplane could actually be made to look like a flying creature. It took several iterations to get the details right.

Attention, Please

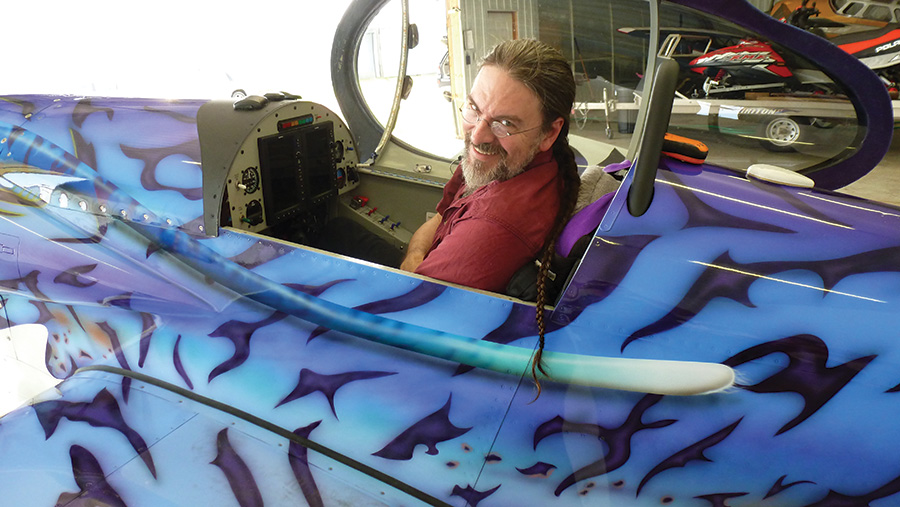

Ever since our RV-3 came out of the paint shop, it has drawn a lot of attention. As we have told people from the first day we revealed it: You can love it or hate it, think it is cool or think it is silly, but if you take a close look, it’s hard not to admire the detail and ability of the artist who did the work.

Deciding to spend a lot of time and money on an airplane’s paint is a personal and somewhat selfish decision. You do it not because it is necessary, but simply because you want to and you can. It is not really a rational decision, but neither is putting a huge stack of IFR avionics into an airplane when you have never used an airplane for travel and don’t have an instrument rating. You may hope to add the rating one day, and, yes, you want to get out more, but this is a goal shared by many and executed by few. It’s like owning a fast sports car but never taking it to a track. You can’t legally use the speed on the highway, but it’s neat to know that you have the fastest car on the block. Like I said, irrational, but sometimes a little irrationality is good for us.

After the concept sketches and model were approved, air-brush artist Scott Draper did these sketches to add his own style to the project and give him something to use as a template.

Origin of an Idea

The idea for our new airplane’s paint scheme came to my wife and I after seeing the 2009 movie Avatar, a science fiction extravaganza featuring incredible flying creatures called Ikrans. The natives of the imaginary planet used them like aerial horses, riding them for hunting and battle, roaming the skies at will. We enjoyed the way the fictional characters bonded with their mounts and flew them with their thoughts. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if an airplane actually felt like that? The RV-3, from everything we had heard, held that promise: a machine that didn’t get in the way of the true experience of flying, enabling the pilot to feel one with the sky.

We were at least a year from finishing the RV-3 when we began discussing the idea, and it went into the stack of hundreds of items we still had to decide on as the build progressed. There was no need to decide on the finished look of the airplane at that early stage, so we went back to pounding rivets and pulling wires. A few months later I found myself at a fly-in with Grady O’Neal, the owner of GLO Custom, the shop in Fort Worth, Texas, that I had used to paint my RV-8 several years before. I pulled O’Neal aside to talk privately about our concept, beginning with the question, “Have you seen Avatar?” A smile crossed his face as he answered, “Yes. Are you talking about those flying creatures?” I knew he was hooked. My next question was simple: Was it possible to do a detailed enough job to make it look good? Our concern was that if we didn’t go all the way, it might look cartoonish and incomplete. We knew that vinyl appliqus were one way of getting extreme detail, but what about paint?

Once the airplane was painted white, Draper began laying out guidelines with tape to define the various parts of the creature.

The Merits of Vinyl

A couple of years earlier, we had seen an airplane at Oshkosh that had been completely vinyl wrapped. It was a small yellow Pulsar with incredible graphics of the owner’s pet bird on the wings and fuselage. As impressive as it was, when we looked at it closely, we immediately thought that such a feat just wouldn’t look good on an aluminum airplane. The vinyl didn’t do a good job of smoothing out surface irregularities such as rivets, and we had tens of thousands of those. Being a composite airplane, the Pulsar was a much more natural choice for this application. So when I presented the idea to O’Neal, I told him that vinyl graphics probably weren’t going to be the answer. We didn’t want to simply paint a picture of an Ikran on the airplane; we wanted the airplane to be the Ikran.

Considerable masking was a part of the overall surface work in preparation for local finishing work.

After the basic outline was masked, Draper began shooting broad areas of color, such as the creature’s tail.

O’Neal smiled as I explained all this and said, “I have just the guy.” O’Neal paints a lot of airplanes, mostly new RVs, and has done just about everything imaginable, including designs with complex nose or tail art. Sometimes he brings in an airbrush artist by the name of Scott “Shark” Draper, who has been in the art business all his life (he told me his second grade teacher recognized his talent and he started getting special attention to develop his skills). He has a portfolio of motorcycles and vans to rival anything you’d find at a large custom show (and has the awards to prove it). It turned out he had been thinking of taking on an entire airplane to expand his repertoire when we came along with our idea. We knew we had the talent in place if we decided to go with the concept.

We were still a long way from committing to the idea, however. First and foremost, we knew it was going to cost a lot of money, and we needed to decide if it was going to be something that would work, along with being pleasing to the eye. I might be a good engineer and know my way around a drafting set, but I am absolutely incapable of freehand drawing or painting. Fortunately, I didn’t need to be. I had an ace in the hole, Gary Zahradka, a friend from my elementary school days who runs his own business, Zahradka Art and Illustration in St. Paul, Minnesota. He makes his living producing art—sculpture, paintings, drawings, you name it. He enjoys the world of fantasy fiction, and I had always admired his dragons. I dropped by his studio when I was in my old hometown, and we sat and talked about the idea for our airplane. If anyone could give us a rendering of an RV-3 in Ikran garb, it would be Zahradka. I commissioned him to do some sketches to see if we could make the Ikran shape and colors work on a rectangular wing and a fuselage with cowl cheeks. Would they look extraneous on the landing gear, and would the overall effect be pleasing? Answering these questions for a small sum of money was better than spending a great deal on paint, only to discover we had made a terrible mistake. As we talked, he sketched on the three-view drawings I had brought, and we both came to the conclusion that it would be difficult to make a decision based on sketches alone. What we needed was a model, something that would flesh out the design in three dimensions.

Fortunately, I had an all-white model of an RV-4. The RV-3 and -4 share a lot in shape and design, and since this model was really an amalgam of RV-3, -4 and -8 parts, I figured that if the Ikran design would work on it, it would work on a -3. I boxed the model up and sent it off to my friend. No deadlines, just do it when you get inspired, I told him. The only real question he had was about our color palette. The Ikrans from the movie ranged from blue/purples to green/blues, and there was a much larger creature, the Toruk, with similar lines in vivid reds and oranges. My wife, Louise, and I admired the looks of the green creatures, and we both love the colors of sunsets, but we figured the Toruk scheme belonged on a much larger airplane, possibly an RV-8. So we ordered a purple harness from Crow Enterprizes and the die was cast. Zahradka stocked up on blues and purples.

Draper frequently referred to his detailed sketches to make sure he wasn’t getting off track. An advantage of doing an organic creature is that symmetry does not need to be exact.

Gestation Period

Months passed, and paint moved to the back of our minds. We knew that eventually we’d pay Zahradka a visit and see what he had come up with, and the next visit saw us sitting on his porch, drinking tea and talking old times. He brought out the model, and we were impressed; the shapes seemed to work. There were some details to work out, but we thought that the concept had enough merit to pursue it. What followed was an interactive design session, with Zahradka ducking into his studio to make changes here and there. We wanted the airplane to look more aggressive, and sweeping the design’s wings forward accomplished that. The cheek cowls called out to be the location for the eyes, and they were added. The swirling of the tail was almost perfect, a design feature that survived to the finished product. When we left that session, we asked him to do one more thing; we had pinned down colors and shapes, but we wanted him to delve into details.

As each detail on the skin was done by hand, no two are alike, lending organic realism to the simulation.

Brushing Up

We still weren’t sure at that point if we could afford to do all of the airbrush work required to pull off the design, so we asked Zahradka to use fine paint markers to detail half of the model, and use broad strokes on the other half as if we were simply painting panels of four different colors. The second half would simulate the airplane being done using traditional aircraft painting “mask and shoot” techniques. A month went by and eventually an email showed up with pictures. This was around Oshkosh 2011, more than a year since our initial thoughts, and we were nearing the end of the build. Paint would be crossing the event horizon, and we would have to make some decisions. Looking closely at the model, we made two decisions. First, the overall concept would work. Second, the less detailed version simply wouldn’t do; it looked too much like a poor cartoon and not enough like a living creature. We were going to have to go all in.

The next step was to send all of the pictures to Grady O’Neal and get an estimate. I had a good idea what a typical paint job would cost, but I had no concept what an airbrush artist would charge. Frankly, we weren’t sure if we wanted to know the answer. We liked the idea of the Ikran, and if we determined it just wasn’t feasible, we’d be disappointed.

No detail was too small to escape Draper’s attention. Here he applies a fade to the pilot-side air vents.

A month went by, and in the meantime we had the airplane flying. When O’Neal heard this, he called and said, “Let’s set up a meeting.” He wanted us to sit down with him and Draper to go over the concept, the detailed designs and what we could do to make it all work. The initial price estimate was pretty high, higher than we thought we could realistically afford. But both O’Neal and Draper were interested enough in the project to invest some time into figuring a way forward, so we arranged to fly the airplane to Fort Worth as soon as it was out of Phase I. O’Neal wanted Draper to see that the RV-3 was much smaller than the two-seat RVs he was used to encountering. He felt that if Draper saw the relative size, he might understand that it was more like a motorcycle than a van. This proved to be true. Draper was excited once he saw the airplane, and we sat down to figure out a way to make it work. The way turned out to be pretty simple. Our initial idea was to do a detailed painting on both the top and the bottom. But when we looked at the airplane sitting on the ground, we realized that putting a lot of detail, or any detail, onto the bottom was a waste. The airplane is small and close enough to the ground that the average person would never see the underside. In the air, a viewer from the ground would see a general shape, but that was about it.

The Trade-Off

My wife thought up a marvelous compromise. She had spent a lot of time looking at airplanes as traffic, and noticed that a darker pattern on the belly made them more visible when banking away. We decided to have O’Neal paint a shadow outline of the upper surfaces on the belly. This would require nothing but masking to the same templates used for the top, then a single shot of grey paint. With this decision, we were able to bring the overall price into the ballpark, so we took a deep breath and gave the go ahead. Draper began sketching; he needed to make the work his own in order to translate it properly onto the finished airplane. We went through several iterations on the design of the head before I had an “Aha!” moment and sent him a picture of a Flying Tigers P-40. The shark’s mouth was just what he needed to see; the spinner became the creature’s nose, and we were on our way.

Eagerly Waiting

We planned to deliver the airplane to GLO on our way to Sun ‘n Fun in April 2012, and we’d see it about seven weeks later. GLO can normally deliver a fully painted new RV in a month, but Draper estimated that his work would add about three weeks to the time frame. We were busy with another airplane project, so it was a great time for the RV-3 to be out of sight, if not out of mind.

The shadow on the airplane’s belly includes the creature’s retracted legs—a detail that adds to the realism.

Once we dropped the airplane off, the normal paint-shop work began. The control surfaces and canopy were removed and fiberglass finishing commenced. Since most of the fiberglass parts on our -3 were built from scratch (with the exception of the wingtips and wheelpants), there was a lot to do. GLO does great fiberglass work, and they do it all the time, so they are much faster than the average builder. I let them fill pinholes and the like using the chemistry they prefer. This took them a couple of weeks, and by week three, the airplane was all-over white with a slightly blue tint to work better with the final coloration. At this point, Draper set up camp at GLO Custom and got to work.

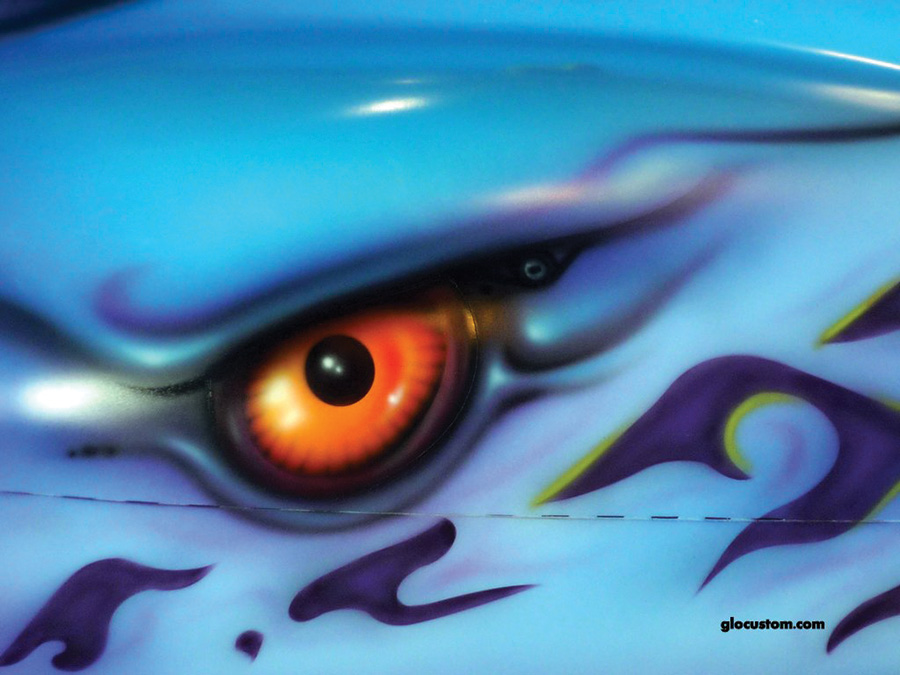

The last details to go on were the eyes and mouth. Draper’s skill with shading makes two dimensions seem like three.

About this time, we paid a visit to see how things were going, and Draper was clearly enjoying the start of his part of the project. We were quite happy with the finished glass and base coat. Because of all the airbrushing, O’Neal was using a two-stage base coat/clear coat system on the airplane, with the colors done between the two.

Pictures passed between Fort Worth and Houston on a regular basis for the next couple of weeks as the Ikran took shape. Draper laid out the broad area of color first and then set in on the details of the texture in the creature’s skin. It was interesting to watch his process on the textures (which some took to be bat shapes). He had several cardboard pieces that resembled homemade French curves. Using these as handheld masks, he was able to shoot with the airbrush and get a variety of shapes. The spinner was done off the airplane, pointed upward on a stand, which gave him the freedom to work all around it without being underneath. One of the trickiest parts of the airplane was having to match shapes when control surfaces were deflected, or the canopy opened and closed. The spots and shapes needed to flow onto parts that were hidden in order to work well.

A&P Brandon Macnicol has disassembled and reassembled more RVs than anyone and has yet to be stumped.

Draper saved the best for last; he loves doing eyes. These and the mouth were the last things to come to life, and they did! I felt a bit like a Hollywood producer when I gave him direction. “I want the face to say, ‘Don’t even think of messing with me and my pilot!'” When I saw the pictures of the nearly finished head, I knew he had gotten it right. We paid a couple of visits to GLO while on other trips during Draper’s time with the airplane.

He finished his work in three weeks, just as expected, and O’Neal once again took over. At this point, the pictures stopped coming. O’Neal is a bit of a showman and wanted to build our anticipation. The last week saw the bottom painted and overall clear coat applied, three coats to add some depth. I was concerned about weight, but was told that the base coat is much thinner and lighter than single-stage paint, and the overall layers weigh about the same when finished. We haven’t yet put the airplane on an accurate set of scales, but based on the careful before/after weighing of a previous GLO project, we figure it is about 15 pounds; the RV-3 is pretty tiny. O’Neal’s longtime partner and A&P, Brandon Macnicol, went to work in the final days on the reassembly of the airplane, which didn’t prove to be any trouble. We arranged a pickup day, and when we showed up, there it was—Tsamsiyu in full and living color!

The gleam in Tsamsiyu’s eye matches the delight of the owners. This RV-3 captures the attention of pilots and non-pilots alike when it appears on airport ramps across the country.

The Big Reveal

The airport locals had seen bits and pieces of what was going on with the airplane, but the crowd was steady that morning at O’Neal’s as we rolled the airplane out into the sun for pictures, the pearl colors glittering with depth and the contrast with the green grass and blue sky stunning. All art is, in the end, subjective by nature—we don’t expect everyone to understand or appreciate a work in the same way. What’s important is if you like what you see when you open the hangar door. But it is pleasing to hear folks appreciate the skill and artistry that went into this job, a salute to O’Neal, Macnicol and Draper, with nods to our concept artist Zahradka and of course the creators of Avatar.

Complex and creative paint doesn’t make the airplane fly any better, or any faster, but it can change the way an owner feels about the aircraft. If this is something you want, take the time to do it right. Build a team of collaborators, and take their ideas to perfect your vision. Make sure that everyone understands the vision, as well as the resources available. Communicate that vision to the team, nurture it and watch it grow. In the end, if you enjoy opening the hangar door every day and smile when you see your creation, it will probably have been worth it.

Nice paint job. A couple decades ago I painted my high wing taildragger to look like a dragon the landing gear became the legs and the wheel pants had talons holding the tires. LOL

My current plane has a paint Scheme much like a lowrider. Green, purple, and blue. Lots of metal flake, Pearl, lace, and murals.

It’s all composite over aluminum tube. Suicide doors, windows slide down inside. And it also has front Wing Windows just like the old cars. Had to use both sides of my brain which was asking a lot. LOL

Two AMR 500 superchargers with clutches on a custom manifold sitting on top of direct Drive type 1 2300. Cam RPMs 1,200 – 3,000.

5.3 power loading

6.2 Wing loading

🤠🏞️🛩️

I am responding to N2B12’s comment: Any chance we can get more info on your “Two AMR 500 superchargers with clutches on a custom manifold sitting on top of direct Drive type 1 2300. Cam RPMs 1,200 – 3,000. 5.3 power loading, 6.2 Wing loading” I am building a single seat all metal Aerobat & the AMR 500 superchargers are getting more attractive & reasonably priced. Dying to see how you built a drive belt configuration for them. Thanks!