The flashlight is on only for a few minutes to check and record the readings from the sight gauges on the cockpit fuel tanks. Now off, it’s dark…really dark. The flight schedule had been planned many months ago to put this, the North Pole leg, at the full moon. Reality intervened to put me two weeks late, now at the dark of the moon. I cup my gloved hand to the Plexiglas to shield the light from the instruments. Polaris really is straight up.

I’m staying pretty busy. Getting position reports off to Gander on the HF takes a lot of time. In between reports I’m adjusting valves for the 10 fuel tanks, trying to keep the center of gravity somewhat in balance. Every hour I take 18 readings and transmit them to the ground crew via satellite text: fuel state, engine parameters, angle of attack, heartbeat and blood oxygen, cockpit temperature, and more. The readings are fairly routine. Only one has kept my attention for several hours…oil sump temperature.

I’ve crossed the North Pole and am now heading south over Ellesmere Island in far northern Canada. The OAT should be warming… it’s not. At the Pole, I record an OAT of -18.4 F (-28°C) at FL 120. I’m four hours south of the Pole and the OAT is still falling, now reading -36.4°F (-38°C) with the oil sump temperature at an uncomfortable 75.2°F (24°C). I’m worried about the oil freezing in the oil cooler, even though I’ve had that airflow closed since just after takeoff in Fairbanks 12 hours ago. A burst oil cooler could ruin my evening.

There are occasionally a few unbusy minutes during which I can’t help but reflect on this trip. The North Pole in January in a little homemade single-engine airplane…how the heck did I convince myself that this was a good idea? What am I doing here? How did this trip come about?

The author on the ramp at Punta Arenas, Chile. The South Pole is 2220 nautical miles from Punta Arenas, about the same distance as New York to San Francisco.

Planning

The planning for this series of flights began over 10 years ago. My wife Sue and I had enjoyed some long flights in the Lancair 320 we had built. We flew it from the U.S. to Kemble, England, for the PFA (Popular Flying Association) rally in 2003, and from there, on to Germany and Holland. That opened our eyes to just what is possible in a little airplane. What about an around-the-world flight? The more we looked at this possibility, the more we found that the 320 could carry adequate fuel or two people, but not both at the same time. A four-place airplane built specifically for long distance would be a much better choice. So, at Sun ‘n Fun in 2004, we ordered a Lancair IV kit.

Non-stop, long-distance practice flight in 2013 from Guam to Jacksonville, Florida. Total distance was 7,051 nautical miles. Time en route was 38 hours, 39 minutes.

The airplane was completed in 2012, and after the normal testing, we embarked upon a series of long-distance tests. These tests culminated in an attempt at the world record for distance in our weight class. That flight was from Guam to Jacksonville, Florida, a distance of 7051 nautical miles (13,059 km) and took 38 hours, 39 minutes, non-stop. With six gallons left, I landed in Jacksonville and was able to claim the record.

Shortly after the distance record, we (even though it is a single-place airplane in this “expedition” mode, there is a team of people working hard on this project, hence the “we”) made our first attempt at the world record for Speed Around the World over both of the Earth’s poles. That attempt was unsuccessful. We made it to Punta Arenas, Chile, and waited eight days for acceptable weather to cross the Southern Ocean to Antarctica. It was late March and too late in the season. A long flight back to the U.S. ended that first attempt.

The long scat tubing is a heater hose. All instruments and avionics are on the left side of the panel, and the right side is completely blank. This allows the space between the panel and the firewall to be used for a 13-gallon header tank.

An official World Record sanctioned by the Fedration Aronautique Internationale, keeper of aviation records since 1905, requires following a strict set of requirements. For this particular record, these requirements include:

- The aircraft must be officially weighed at the maximum weight that it will be flown at during the record attempt.

- The flight must fly directly over both the North and South Poles.

- The northbound and southbound equator crossings must be separated by a minimum of 120 degrees longitude.

- All declared points must be reached in the order that they were declared.

Speed is computed by dividing the total great circle distance between declared points by the total time. Total time is computed from the first takeoff to the last landing back at the starting point. Flying other than directly between declared points is allowed, but is not counted in the total distance.

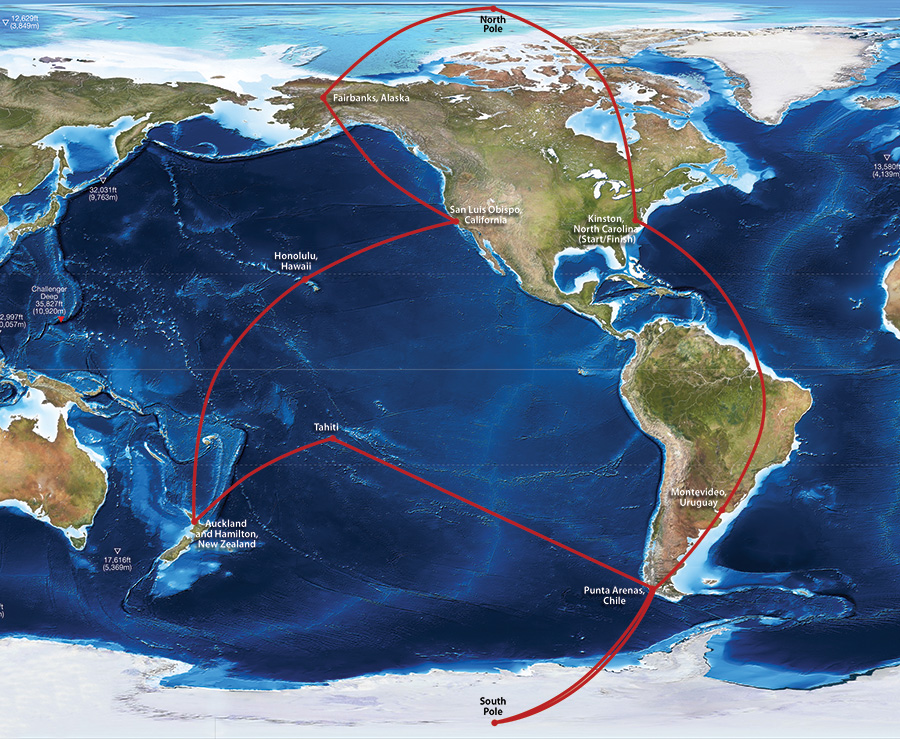

The route flown: 31,118 nautical miles, 24 days, 174.9 hours—lots and lots of ocean with some ice here and there.

The Journey Begins

We chose Kinston, North Carolina, KISO, as our start/end airport. Kinston has a long 11,500-foot runway (needed at our extreme weight), a tower (needed to attest to takeoff and landing times), and an excellent FBO (thanks, Kinston Jet Center). Kinston is also geographically situated such that we had a clear route through the warning areas that exist all along the U.S. East Coast.

Since we needed to fuel to maximum for weighing at Kinston, we planned the first leg to be our longest, east to cross the equator at 44 degrees west longitude, and then south across Brazil to Montevideo, Uruguay, SUAA, a distance of 5286 nautical miles and planned for 28 hours. At our max fuel weight, takeoffs are always a challenge. Normal rotation speed for this airplane would be around 65 knots. At max weight rotation is 105 knots, and the wheels leave the ground at 110-115 knots. Once off the ground, climb rate is 100 fpm or less until an airspeed of 160 knots is reached. Then it can maintain perhaps 400 fpm until 8000 feet or so, when it will climb no further until fuel weight is burned off. The aft CG makes the airplane divergently unstable. The Lancair IV, normally a pleasant-to-fly, responsive aircraft, is an ugly, difficult-to-fly, poorly performing pig at this weight and CG. Use of the autopilot is out of the question for the first five or six hours. After this, the CG is such that, in smooth air, the autopilot can be engaged. This is always a major relief. Now more attention can be devoted to weather avoidance, navigation, fuel management, communication with the ground crew, and perhaps a moment or two to eat, drink, exercise, and think.

Landing at the Angel S. Adami airport, SUAA, in Montevideo was a great pleasure. Adami is a wonderful little general aviation airport with quick and easy customs, self-serve avgas, and best of all, the friendly face of Gualdemar Gutierrez. We had been communicating with Gualdemar for many months prior to our arrival. He had arranged everything: fuel, transportation to the hotel, customs, etc. He had agreed to accept a package that we had sent ahead (clean underwear, PowerBars, oil, CamGuard, etc.). Since our next leg would be a relatively short leg to Punta Arenas, Chile, we could afford to carry some supplies from there.

The weather the next morning was acceptable and the short hop (1329 nautical miles, 7 hours) to Punta Arenas went quite smoothly. Argentina ATC was competent and friendly as we passed this leg almost entirely over their country. Good weather prevailed for landing in Punta Arenas, Chile.

Good News, Bad News

After clearing customs, the next stop was the met office. I had found on my previous flight to Punta Arenas that the meteorologists here were first class. They had up-to-date equipment and were extremely knowledgeable, especially concerning Antarctic weather. They had good and bad news for me. The flight from Punta Arenas to the South Pole the next day should be during a rare window of excellent weather and only moderate headwinds. There was, however, bad weather over the Southern Ocean on the way from Antarctica to New Zealand. Since the weather from South America to the Pole looked unusually good, the decision was made to take advantage of the good weather and depart for the Pole the next day.

For years I had known that this leg from South America across the South Pole to New Zealand would be the most critical and dangerous leg of the entire project. The Southern Ocean is infamous for extreme and rapidly changing weather. Weather reporting stations are few and possible landing sites almost non-existent.

A maximum-weight takeoff with the full 361-gallon fuel load and a very slow climb over the Strait of Magellan toward the mountains of southern Tierra del Fuego started this leg. With excellent visibility, the mountains and glaciers at the southern tip of the continent were soon visible. Monte Sarmiento at 7175 feet was the highest obstacle in my way. I was able to hold 10,000 feet as I passed just to the west of this spectacular mountain. In the words of Charles Darwin, “the most sublime spectacle in Tierra del Fuego.”

Once past Tierra del Fuego, it’s over the Drake Passage toward Antarctica. Hours pass with the open ocean mostly obscured by low clouds. Just a few higher cumulus are visible on the southeastern horiz…wait a minute…those aren’t clouds. They’re the mountains of the Antarctic Peninsula! The first view of this magic continent while still 200 miles away is something that I’ll never forget. The view gets more spectacular the closer I get. My route takes me over Mount Stephenson on Alexander Island. This is the fourth highest peak in Antarctica and probably the most visually impressive since it rises directly from the sea in one unbroken 60-degree slope of rock to 9800 feet.

I continue following the 71-degree west meridian toward the Pole. Passing over the peninsula and then over the western edge of the Ronne Ice Shelf, I find myself in stratus clouds. The temperature is well below -4°F (-20°C) and I encounter no ice. Once out of the stratus, I can see the Sentinel Range far to the west and Vinson Massif, the highest point in Antarctica at 16,067 feet, impressive even from a distance.

Antarctica

The interior of the Antarctic continent is surprisingly featureless. Hundreds of miles pass and it looks as if I’m flying over a smooth cloud layer. Only occasional crevasses and rock outcroppings show that it’s snow and ice. The GPS units are now showing a maddeningly decreasing groundspeed. The headwinds are stronger than forecast—considerably stronger. By the time I reach 85 degrees south latitude, I’m 1 hour and 1 minute behind flight plan and worse, below flight plan fuel. This leg is a 5383-nautical-mile flight into increasing headwinds, questionable weather, a high probability of icing on the second crossing of the Southern Ocean, and no place to land, short of New Zealand.

It’s decision time. The ground crew and I reach the frustrating conclusion that to continue past the Pole toward New Zealand would put the flight into a far too risky and uncertain situation. We decide to continue to the Pole and then return to Punta Arenas. It’s 2220 nautical miles from Punta Arenas to the Pole, the distance from New York to San Francisco…and another 2220 miles back, but still shorter than continuing to New Zealand. I work out a flight plan for the return and advise ATC on HF of our decision.

Finally, over the nose, I see Amundsen-Scott Station, the U.S. research base at the South Pole. It looks like a junkyard at the end of the earth. A few circles around the Pole, snap a few photos and I’m on my way north back to Punta Arenas.

Airframe Icing

Antarctica is known for rapidly changing weather. It did not disappoint. Even over the same areas that I had flown over just a few hours ago, I notice more clouds. Over the continent I’m not worried about airframe icing since the temperature is well below -4°F (-20°C). Over the Southern Ocean, however, just 100 miles short of South America, with warming temperature and increasing cloud cover, I encounter ice. Just a little at first, but on the thin Lancair airfoils, it’s enough to appreciably degrade performance. It soon becomes obvious that I cannot remain in this situation for long. I’ve been descending to remain below the clouds. I’m at FL 140 now. I check the OAT and calculate how low I need to descend to find above-freezing temperatures—6000 feet should do it—but it doesn’t. At 5000 feet the ice finally starts melting…slowly. But now, I’m getting close to Tierra del Fuego and the mountains there. I need to get back up to at least 10,000 to clear the rocks. Luckily, as I continue north, the temperature continues to increase and I’m able to climb back to a safe altitude free of ice.

Back in Punta Arenas I now have a new set of challenges to face. I need to do the oil change that had been planned for New Zealand. Julio Sopik, my friend and handler in Chile, is able to find a case of oil. We do an oil change on the cold ramp in a 40-knot wind which is pretty normal weather in this part of the world.

I have made it to the Pole so as far as the official record is concerned—I do not need to return there. Since Hamilton, New Zealand, has been declared, I still have to get there somehow. The most direct route will take me well back into the Southern Ocean into 50- to 60-knot headwinds and, very likely, icing. Although we keep looking at this option, we explore what other possibilities are available.

Easter Island would be a great stop, if only they had avgas. They don’t. We could arrive at Easter Island with some tanks still full of avgas. Would car gas be a possibility? We could take off and climb on avgas and then at low power cruise start burning the car gas. Consultations are made with engine experts back in the States, and it is determined that this would probably work…probably…not a comforting thought when flying thousands of miles over open ocean.

How about Raratonga? Pretty far, but might be possible. Tahiti could work. We search for avgas there and find none. Then, Ewan Smith from Air Raratonga contacts the team and finds three barrels of avgas in Tahiti. Super! We file the flight plan for Tahiti. But just before departure a message arrives that Tahiti has refused our flight plan. Seems that they require 72 hours to issue a landing permit…no exceptions.

Bad news from Tahiti: They rejected the author’s flight plan. It seems they require 72 hours to issue a landing permit.