I’ve always been fascinated by the early flying machines at the dawn of aviation. Lucky for us, there were really bold pilots willing to take chances and tread while others stood by and watched. However, if you follow some of the early pilots’ careers, it becomes very clear that longevity was not always in the cards. The old adage of “there are old pilots and bold pilots, but no old bold pilots” rings true. The pilots back then were truly pioneers, with rickety machines and unreliable powerplants. A certain amount of bravado and devil-may-care attitude was probably required, and if it wasn’t for them, aviation progress may have been much slower.

This is the author’s first airplane, which unfortunately was destroyed while doing low-level aerobatics with the second owner, killing the pilot and passenger.

As aviation continued, methodical approaches to new designs and flight testing came to be, albeit not without some dramatic loss of lives. The disastrous demonstration flight of the B-17 prototype to the Army actually ushered in the use of checklists and a realization that airplanes were becoming very complicated machines. However, as of yet, no one has created a self-check checklist of the pilot, short of medical requirements.

It’s always been so disappointing to me to see some pilots continue to do dumb and stupid things, giving the rest of us a bad reputation. I haven’t figured out if aviation creates the daredevil/showboat mentality in the pilot, or if it is just Darwinian behavior. I do know some of them should not be allowed in an airplane, at least one with passengers. To date, two airplanes I built have crashed performing low-level aerobatics, killing four people. It’s so unnecessary, and I am not certain how we should proactively deal with it. I have tried multiple times to intercede and have not been successful. We currently have another potential one unfolding in our neighborhood, and I fear the outcome will eventually be the same.

Like Father, Like Son

Let me share with you a few examples of careless behavior with very tragic consequences. Way back in 1981, when I finished my RV-4, the Christen Eagles were the hottest thing going. The kits were fantastic, the paint jobs were to die for, and we all watched Tom Poberezny and the Eagles Aerobatic Team perform at Oshkosh. As luck would have it, back at my home airport in Elyria, Ohio, a father and son team had just recently finished one and wanted to share a hangar with me. The son was older than I was, and the father had been a very successful finish carpenter, the skills of which transferred very nicely to some parts of the Eagle. Theirs was just as beautiful as any other one I had seen, and I couldn’t wait to get a ride in it.

I learned that the son was a recently minted Private Pilot with 69 hours total time, and that they could not get insurance for him until he had 100 hours. No problem.

I could wait for my ride. Then it happened. One beautiful day I helped get the airplane out of the hangar so he could go flying and I watched him immediately roll on takeoff and climb-out inverted! Right then I knew I would never get my ride. There’s no doubt I would love to sit in the cockpit and view that takeoff, as long as someone qualified like Tom Poberezny was at the controls. It must be a real rush. Come to think of it, it would probably even be a greater rush with a low-time pilot at the controls hoping the outcome would be the same! I still remember coming home and telling Carol I was never going to get my ride in the Eagle.

This was the author’s favorite Kitfox, especially since his younger son Nick soloed in it. Unfortunately, the second owner also crashed it, killing two while performing low-level aerobatics.

After watching the same performance, including loops on takeoff, I worked up the courage to speak with the father. Boy, that was a mistake. I was basically ostracized, they moved out of my hangar, and the next time I saw the dad was at the funeral for his son, caused by performing a loop on takeoff. What a surprise! I remember hearing about it on the news one morning on the way to work. Even though I saw it coming, I was quite shocked. It was the first personal friend in aviation that was killed in an air crash. Unfortunately, there would be more.

What was even more shocking was what happened next. At the funeral, before I could say anything, the father said that there was something wrong with that airplane and that he was going to rebuild it to figure it out. Huh? By the way, I forgot to mention that about a year earlier, dad had run the very same aircraft out of fuel and landed it in Lake Erie, requiring a coast guard tow to shore. I was dumbfounded, but kept my mouth shut. Not unexpectedly, he did rebuild it and proceeded to kill himself and a passenger about a year later doing low-level aerobatics. I still can’t fathom the unwillingness by some pilots to take a look at themselves instead of the airplane.

Good Airplanes, Bad Decisions

I eventually sold my RV-4, thinking I could build a Prescott Pusher to carry the four-seat family I now had. Prescott had really great marketing, but as some of us were soon to figure out, it was really only a two-seat airplane and required above-average piloting skills. Luckily for me, I survived that venture, but would have to wait a few more years for Van to design and market the RV-10. In the meantime, a few more years went by, 20 to be exact, and I received a phone call that my RV-4 had crashed, killing two people. I was mortified, until I learned that they were headed home from an airshow and were seen doing low-level rolls and loops at 250 feet right up until the crash! You’ve got to be kidding me. The owner was 70 years old. I guess the desire to showboat sometimes never goes away.

A Kitfox Speedster I built was also involved in an accident. Some of you may remember that the Speedster was an aerobatic version of the Kitfox, and many of us saw Jimmy Franklin put on quite a show at Oshkosh with the fluorescent green factory demonstrator. Jimmy’s show was so low that more than once, we thought he crashed in between the taxiway and Runway 18/36, but it was just an optical illusion due to the dip in the terrain. While I thoroughly tested mine during Phase I, including taking it to 51/2 G’s, it was all flown way up high. After flying it for 10 years and having soloed my youngest son in it, I sold it to build an RV-6. The Speedster was a great fun machine! On the day I sold it, we watched as the new owner and his flight instructor took off and then came around in a high-banked, high-speed pass with the engine screaming like I had never heard it before. I remarked that I hoped we wouldn’t hear about this one, too.

That was February. On Christmas Eve the same year, I received a phone call from a radio station in Colorado asking if I knew that an airplane I built had crashed, killing two people. I was at a loss for words, but expressed my condolences to the families and hung up. Within a few minutes we learned that hunters had observed the aircraft flying low and doing vertical pull-ups, before descending straight down and recovering. The airplane had gone away and returned a short time later, executing the same maneuver over a frozen lake. This time the outcome was not successful, and the Kitfox nosedived straight into the frozen lake, killing both the pilot and the passenger. We came to learn that on the first flight, he had his younger brother on board and had returned to the airport to pick up his friend. His brother sure was extremely lucky, but not so his friend. His friend was much heavier, and the weight difference could have been a contributing factor to the accident. The light weight and low horsepower of the Kitfox requires careful energy management during vertical maneuvering, a characteristic unfamiliar to an untrained pilot.

I felt really terrible about this accident because I had come to know the father during the sales process. He was buying it for his 26-year-old son to fly, and he planned to learn to fly in it as well. I did call him on Christmas Day to express my condolences. Between conversations with his dad and the NTSB inspector, I came to learn that the son had somewhat of a history of showboating.

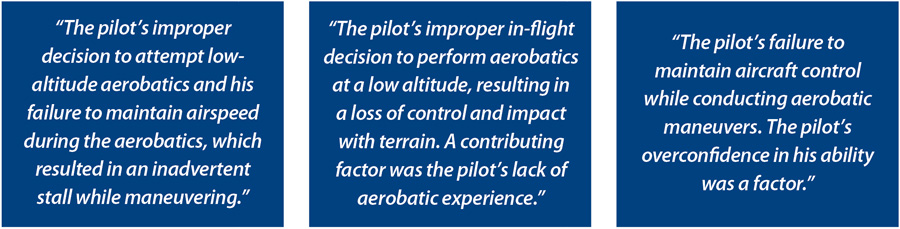

So here it was again. Many people could see it coming, and yet somehow failed to stop the inevitable from happening. I’m sure many of you out there have similar stories to tell of lost friends and/or loved ones who are no longer with us due to antics in airplanes. I’ve even participated in interventions with pilots that have a reputation for taking unnecessary risks, whether it is with poor decision-making regarding weather or fuel planning, or showboating in a way that could cause harm to others. All of the interventions have been unsuccessful. At this point I am not sure what can be done to stop the proverbial train wreck when we see it happening. While you can read the details in the reports (NYC07LA148, DEN06LA026, CHI86FEX05, BFO94LA161) at the NTSB web site, they all had the same common causes spelled out: overconfidence, inexperience, low-level aerobatics, and poor decision-making. Only one had a low-altitude waiver, and that was for 500 feet.

Call the FAA?

No one really likes to get the FAA involved, and I certainly agree that there should be other courses of action. I question if we really do enough as fellow pilots to call out unnecessary risk taking. Could or should the biennial flight review (BFR) be a place to address it with offending pilots? Should offending pilots be required to take an online course that shows them the cruel hard facts? Those pilots who have an attitude that it always happens to someone else are the hardest to convince that they might be the problem. I know I haven’t stumbled upon the magic solution yet, and I certainly welcome feedback from our readers on any successes or ideas you may have.

In the meantime, I will continue to call out risky behavior when I see it, even if it means losing friends and being ostracized. One of my favorite aviation phrases goes like this: “Superior pilots use their superior judgment in order to avoid needing their superior skills.” I think if we could get all pilots to abide by that creed, we would have a lot more fun!

![]()

Vic Syracuse is a Commercial Pilot and CFII with ASMEL/ASES ratings, an A&P, DAR, and EAA Technical Advisor and Flight Counselor. Passionately involved in aviation for over 36 years, he has built nine award-winning aircraft and has logged over 7500 hours in 69 different kinds of aircraft. Vic had a career in technology as a senior-level executive and volunteers as a Young Eagle pilot and Angel Flight pilot. He also has his own sport aviation business called Base Leg Aviation.