A decade ago, when the FAA and ASTM were dickering over what became the Light Sport Aircraft rule, limitations on weight and performance—but not power—bubbled to the top of the discussion. The airplanes were supposed to be less expensive, light, and simple, but the rule didn’t say they couldn’t have neck-snapping power-to-weight ratios, and thus the era of the 180-hp production Light Sport is upon us.

And the bubbling continues as American Legend gears up to offer the Super Legend HP as a kit, including a builder-assist option. The Super Legend HP is essentially the Super Legend airframe fitted with Continental’s increasingly popular 180-hp O-340 Titan engine, a stroked version of the Lycoming-style O-320 that has proven a mainstay powerplant for half a century. This engine has found wide acceptance in the Experimental market, and when CubCrafters jollied it through the ASTM approval process, it became the first such engine of its type to find practical application in LSAs. Just for the record, the CubCrafters version is a different engine, lighter and with slightly different accessories than Continental offers for everyone else. The Titan’s development has proven somewhat of a bonanza for homebuilders because there’s a wide variety of accessories and configurations for this engine. (See the engine sidebar for more details.)

That buyers are choosing this engine in what passes for droves these days, proves what aircraft manufacturers and salesmen have known all along: When writing a low six-figure check for a new airplane, owners want all the options and, no disrespect to ASTM, they don’t want pokey, underpowered airframes. Neither do builders, apparently, who are still investing most of a hundred grand to bring these projects to completion. Just because a would-be LSA or E/A-B driver will never need tundra tires and a 50-foot takeoff roll for a Saturday morning toot around the county, doesn’t mean they’re not willing to pay for such things.

The HP’s panel is well designed with sufficient—if not generous—room for basic avionics. Builders can eliminate analog instruments in favor of an all-digital installation.

With space on the right side of the panel tight, the LSA version we flew had a Trig transponder and com radio. Trig offers ADS-B capability with its transponders.

Enduring Super Cub

With its Cub-type airframes, American Legend has attracted a small but loyal customer base, plying the same market as CubCrafters, Aerotrek, RANs and Kitfox—the taildragging rag-and-tube crowd. (Oh, and did we mention Kitfox and RANs also have their own versions of Titan-powered airframes?)

The original Legend, available as a kit and fly-away LSA, has the Continental O-200-D, a lightened version of the original 100-hp O-200. The Super Legend followed, with the Lycoming YO-233, a lighter version of the 115-hp O-235. When it appeared four years ago, half of Legend’s sales were Super Legends, and the company’s Darin Hart expects similar response to the Titan-powered Super Legend HP, with a smattering of those shipped as E/A-B kits.

The airframe construction is conventional, with Ceconite 102 fabric and Poly-Tone coating over a welded 4130 fuselage cage. For builders, that fuse comes pre-welded as one of four discrete kits in a four-kit package.

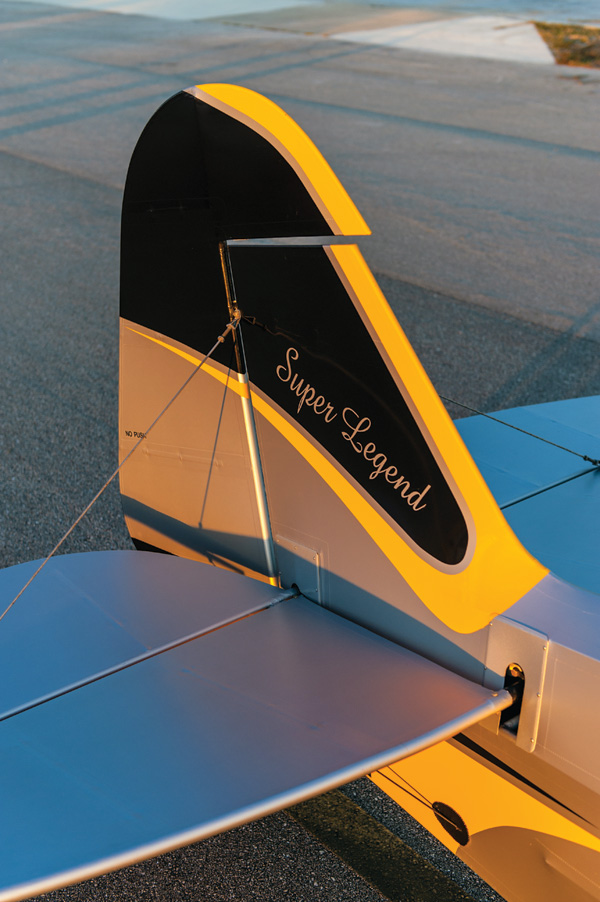

When the Super Legend first appeared, the company increased the size of the horizontal stab/elevator to provide about 18% more surface area. That’s not too noticeable just looking at the airplanes side-by-side, but does provide some increased pitch authority. Unique to the Legend design are doors on both sides of the cabin, a welcome feature for hot-day ground ops and transformational for float work, sometimes saving the need to dance across a walk wire when docking or mooring.

With the Titan’s higher power comes higher weight, and that chews into the airplane’s useful load for the LSA version. But for the E/A-B, think of Super Cub-type useful loads and a higher empty weight by whatever equipment and accessories a builder wants to add that an LSA owner can’t. And because the Super Legend has payload to burn, there’s more than enough margin to lard it up with stuff, even if it’s hauling floats. (Legend offers its own in-house carbon amphibious float system.)

The Titan O-340 can be fitted with one of two Catto props, an 80×50 cruise prop or an 84×42 climb prop.

Weight wise, Hart told us the original O-200 weighs about 199 pounds and the Lycoming O-233 used in the Super Legend adds 15 pounds to that. The Titan tips in at 248 pounds, which means the airplane went on a serious diet to stay inside the 1320-pound LSA weight limit.

The heaver weight up front does shift the CG forward slightly, but it still stays within 3 inches of the forward limit when the airplane is occupied by two pilots. (The pilot weight is concentrated on or aft of the CG datum point.)

The original Legend has about a 500-pound LSA useful load on an empty weight of 825 pounds, but the Titan-equipped HP is at least 80 pounds heavier than that, with an empty weight of about 905 pounds. In fact, it pushes the limit on LSA empty weight requirements. E/A-B builders needn’t be constrained by the stingy empty limit, and the airframe itself is engineered to the same gross weight as the Super Cub—1750 pounds. That translates to 800 pounds of useful load. With 30 gallons of useful fuel aboard, the airplane can steam along on reduced power at 5 gph and cruise for five hours comfortably at about 92 to 95 mph.

The Legend HP sports Grove brakes that can be either heel or toe activated. Either way, they have sufficient energy to put the airplane on its nose.

And this gets us to the dirty little secret of Light Sport Aircraft that the E/A-B world can rightfully snicker at. The arbitrarily low gross weight is the most oft-ignored rule in aviation. The blunt truth is that with full fuel and two 200-pounders aboard, the E/A-B version would still be 250 pounds under that limit. Make your own moral judgment on the advisability of doing this or not, but the airplane can be flown safely at that loading, and pilots who have flown the Super Cub in the Alaska outback will note that it has been flown heavier. By a lot.

Tundra tires have become a bold fashion statement for Cubs. Nice if you need them, but they cost a bundle and rob speed.

Flying the HP

Aerodynamics being what they are, stuffing this much power into a light airframe doesn’t do much for cruise speed. Legend gives the maximum cruise speed of the HP as 104 mph or about 5 to 7 mph faster than the Super Legend. For cross-country flying, think of it as an 80- to 90-mph airplane and plan accordingly.

But takeoffs, well, they’re something else entirely. The company claims a minimum takeoff roll of 35 feet, followed by a maximum climb rate of up to 2000 fpm.

That takeoff performance may be achievable with the proper technique, but it requires a bit of nerve, using power to jack the tail up against the brakes and hauling the airplane off the runway with an abrupt tug. At Sebring earlier this year, we might have used 100 feet of runway without trying very hard. Similarly, with two aboard, we climbed at 1500 fpm with no heroics required. But that also means you get to pattern altitude by the turn from crosswind to downwind and better grab a handful of throttle reduction to keep from overrunning the altitude.

Legend gives the maximum cruise speed of the HP as 104 mph. For cross-country flying, think of it as an 80- to 90-mph airplane and plan accordingly.

Although the Cub airframe wouldn’t be confused with something slick, it actually takes determination to slow it down on final approach. With a full-flap stall speed of 28 mph, the airplane can be flown at 50 mph or even slower on short final. Getting there takes effort, however, because until the airframe is dirtied up and slowed up, all it wants to do is glide at an angle that’s surprisingly flat. It will slip, of course, even with full flaps, but that didn’t seem to add much to the descent rate.

The view over the nose is typical Cub, albeit good enough that no S-turning is required on the ground. Solo is from the front.

Nonetheless, a max-performance short-field landing with full flaps and power on can get the airplane into a postage-stamp runway. With its surplus power, there’s little worry about getting unrecoverably behind the power curve.

The demo airplane we flew was equipped with Desser’s 28-inch tundra tires, which may or may not absorb bounces on landings. The outcome depends on what kind of descent rate you’re expecting them to absorb. Damping springs in the landing gear help, but what springs give, they return if they’re compressed too abruptly.

The tires are mounted on 8-inch rims from Grove. Frankly, we’re not fans of these big tires unless they’re necessary for operating over rough or soft terrain. Yeah, they look cool, but they make the airplane more difficult to ingress and egress and, in our view, seem to move the center of mass higher, making the airplane feel less planted during ground handling. Skittish isn’t the right word, but you get the picture.

The Grove brakes are powerful and require deft footwork because they’re more than capable of putting the airplane on its nose. And indeed, that happened on another press demo flight of the HP we flew, although it wasn’t clear if it related to brake application. The airplanes can have either toe or heel brakes. From the front seat, we found the heel brakes a little tricky to apply because of the distance from the rudder pedals to the brake pedals. But that’s typical Super Cub and maybe a good thing to avoid the aforementioned nose prangs. But toe brakes have the advantage of being easier to get to and apply gently for a pilot used to them. Given the choice, we would take modern toe brakes, thanks.

Cabin appointments in the Legend HP are comfortable, if not luxurious. The seats are the same weight-saving bungee designs Legend introduced in the Super Legend. The windows open in flight, held fast by a new clip that’s easier to use than the previous design. Visibility in flight and on the ground is excellent from the front seat. There’s no need for S-turns.

One thing we would like to see improved is the hinge point for the flap handle. It’s almost aligned with the pilot’s shoulder axis, and we found it awkward to manipulate for that last notch of flap. Rotator cuff patients might feel a twinge. A forward bend in the handle might help.

With the higher-performance airplane comes a higher price, of course. The four basic kits (see “What’s in the Box” sidebar) come to $57,250. That includes a firewall forward kit, but not the engine. Add $29,500 for the Titan, and you come to $86,750 less paint, prop, avionics, and basic electrics.

For comparison, the base price of the flyaway LSA Legend with the classic Cub cowl is $136,900, while the Super Legend base is $154,900. The Super Legend HP starts at $164,900 and the version we flew—with Garmin avionics, Trig ADS-B Out, AeroLED landing lights, and a leather interior spec’d out at $195,000. For more information, contact American Legend at www.legend.aero or 903-885-7000.