Well, suppose you’d like to build an airplane. Nothing super fast, no complex systems or fancy instrument panels, no expensive space-age materials, no need to be aerobatic. Something, well, traditional…like the Aeronca Champ your father and uncle owned when you were growing up.

Canadian Ron Mason had the same idea back in the 1970s.

Ron’s main interest was missionary flying. That required a very inexpensive airplane because missionary work is usually done on a financial shoestring. It had to be dead-simple structure that could survive vigorous use, even abuse, and still fly safely. It had to be built of easily obtainable and understandable materials and maintained in the field with a small box of elementary tools.

Philip Groelz designed a cowl flap on the side to replace the traditional bottom firewall exit. The engine cools well, but any decrease in drag is hard to detect in the high-drag airframe.

Using those parameters, he designed the Christavia. Built with traditional steel tube fuselage/wood wing structure and covered with fabric, it emerged as a two-seat tandem airplane with a high wing and a tailwheel. In fact, it looked very much like a Champ. Although very few, if any, actually ended up in the mission field, the design found a niche with homebuilders. Ron drew up a set of construction drawings and through his company, Elmwood Aviation, sold quite a few sets. Elmwood seems to have gone dormant, but Christavia plans and material packages are still available through Aircraft Spruce.

Philip Groelz’s Christavia

This project started in 1991 when a young man in Estacada, Oregon, purchased an early set of plans. He worked on it for a couple years, making the trusswork wood wing ribs and welding up one side of the fuselage. It didn’t take long for him to realize the magnitude of his undertaking. The discouragement of slow progress, a job transfer, and the birth of his children caused him to set the project aside.

Simple doesn’t mean unsophisticated. An AFS 5600 does all the nav/engine monitoring/flight instrument chores and records everything. Traditional round instruments include an altimeter and ASI, com radio and transponder.

In 1998 it was picked up by EAA Chapter 902, based in Mulino, Oregon, as a chapter project. Progress was slow as volunteer workers came and went. Thirty-six different people entered their names in the builder’s log, and the project moved from one location to another several times. Eventually the wings were nearly ready for fabric, the fuselage was on the gear—and the effort ran out of gas. It sat, rarely touched, until 2010 when Philip Groelz—one of the chapter members who had worked on it—acquired the project and took it home to his hangar in Canby, Oregon.

Philip, who had finished and flown a Wittman Tailwind several years before, was the perfect guy for the job. Raised on a farm with a father who’d taught him the basics of machining, blacksmithing, and keeping equipment running, he graduated from the University of Nebraska with a degree in electrical engineering. Combine a blacksmith with an engineer and a Tailwind builder, and you’ve got someone who can solve problems and build just about anything. He was under no illusions about how much work was left. “The Tailwind taught me that a plansbuilt ‘rag and tube’ airplane requires, at the very least, two man-years. I figured the Christavia, even though it had been started almost 20 years earlier, had about a man-year’s worth of work actually accomplished. That left me with a man-year left to go…maybe more.”

“More” it turned out to be. Philip finished the control system, fuel system, seats, landing gear struts, and welded on the scores of little metal tabs that are the difference between something that looks like a steel tube fuselage and something that will actually function as one. He installed some custom touches, including GlaStar-like strakes in front of the ailerons.

He chose the water-based Stewart covering system. “I had to learn some different techniques than I’d used with traditional dope systems,” Philip says, “but the Stewart people were always available with good advice. The water-based components were a pleasure to use. I never needed anything more than a dust mask, and I could clean the guns and mixing cups with a hose on the lawn.”

By the time he finished installing an O-200 Continental, with a custom side-exit cooling system and cowl flap, it was 2013. In 2014 he declared it finished and rolled it out to the grass runway behind his house. In deference to his farm-boy heritage, Philip painted it John Deere green and yellow (complete with leaping deer emblem!). The first flight was delayed for a couple weeks when calculations showed that weight and balance data supplied with the plans just couldn’t be right, and the battery had to be moved from the rear fuselage to the firewall.

Becky and Bruce Breckinridge’s Christavia

Meanwhile, in a hangar not far away, Becky and Bruce Breckinridge were working on an RV-10. They had actually completed the empennage and most of the wings when they made a hard right turn and shelved the project to build a…Christavia.

When asked why they’d decided on an airplane that could hardly be further from the RV-10 in mission and building process, Becky says it was simple:

“We were given, free, a small Continental engine. When we looked ahead, the price of an IO-540 and a constant-speed propeller that the RV-10 requires was pretty daunting. Since the engine seemed to be the biggest expense, we chose another project that could use our free engine. Besides, I really wanted to build something. The RV-10 is a wonderful kit, but so much is already done when you get it that you’re really assembling an airplane, not building it.”

Becky got her wish—in spades. She and Bruce have built every part of the Christavia airframe from raw material. Becky took welding classes at the local community college—”I was the only woman in a class of mostly ex-cons trying to learn a trade,” she remembers. “But we all learned together.”

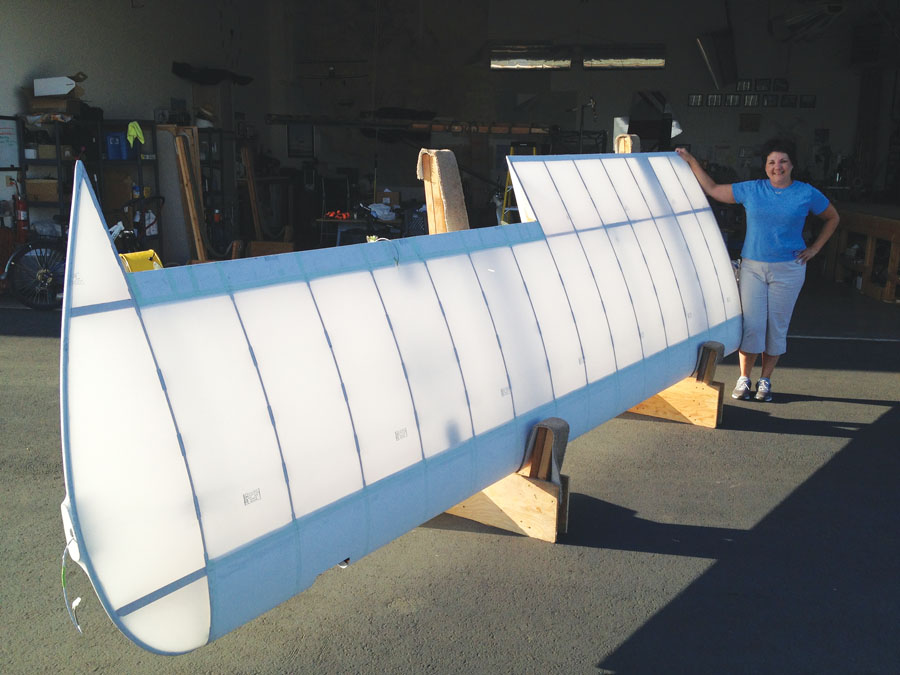

She cut, coped, and welded every tube in the Christavia fuselage. Together they fabricated the thousands of small wood pieces that make up a set of Christavia wings and later covered the airplane with the Stits process. Painting in their leased hangar wasn’t practical, so Bruce trailered the major components to a PVC-pipe and Visqueen paint booth he’d built in their home garage and set about learning to paint.

The resulting airplane is beautiful. The craftsmanship throughout is excellent, with custom touches like the rudder pedals and steps that are positively artistic. Bruce’s maroon and cream paint job is flawless. The welding and woodwork are first class, as is the covering job. With her name scripted on the vertical fin and interior sidewall, “Rosebud” is in the finishing stages. Becky has made an extremely tidy set of baffles for the engine, the cowl is finished and painted, and while there are lots of little jobs remaining, first flight can’t be too far off. Becky is getting some tailwheel time in a Champ, and the entire neighborhood is anxious to see this seven-year project fly!

Flying a Christavia

So, after all the work, what is a Christavia like to fly? In a real act of trust, Philip gave me the chance to find out. He gave me a walkaround of the Leaping Deer(e) and turned me loose.

Shoehorning my less-than-agile 6-foot-3-inch frame into the front seat took some planning, but once I was in, everything seemed to be in the right place: stick in right hand, throttle in left, trim on the left sidewall, instruments and short nose right in front. The O-200 starts easily. The Christavia has straight stacks, so at idle the engine note is very “barky”—a Chihuahua trying to convince the world it’s a Doberman.

The covered woodwork is very light and strong. The wings include nav and landing lights and small white lights that shine straight down—for camping under the wing.

Taxiing is easy—the short nose and tall seating position make it easy to see where you’re going, and the tailwheel steering (and occasionally brake) make it easy to get where you want to go. At the end of the runway, the run-up is stone simple. There’s only one tank and a fixed-pitch prop, so wiggle the controls, check the temps and fuel, cycle the magnetos, and you’re ready to go.

This airplane weighs about 850 pounds. Philip paid a lot of attention to keeping his airplane light, so while the 750 pounds on the plans might be possible with a non-electric and extremely basic airplane, I suspect most Christavias will weigh at least as much as Philip’s and probably more.

Rosebud ready to fly. Master pilot Larry Beck made the first flight shortly after this photo was taken.

Acceleration is decent with a semi-climb prop. The tailwheel comes a few inches off the ground, and the big wing takes over after several seconds and about 600 feet have gone by. With no drama at all, you’re flying. Climb, with just one person aboard, averages about 600 fpm. Once you level out, you realize that you’re flying a high-drag airplane. It hits a wall at about 85 knots—maybe 90 if you push the throttle hard enough—so there’s no point flailing the poor beast. Set the power for about 80 knots and enjoy the ride.

Controls are positive. Roll is slow, and it takes some rudder to stay coordinated. It works a bit better if you start the roll with the rudder and come in with aileron, but nothing seems difficult or unnatural. Power-off stalls, at least in this individual airplane, were almost impossible. With the stick and throttle both at the rear stop, the airplane settles into a mushy descent with no detectable stall break. I told Philip that I thought it could use some more elevator travel, but he’s happy with the airplane as it is and sees no reason to change it. The behavior, even when provoked, is so docile it’s hard to argue with that.

I made no attempt at power-on stalls or spins and completely forgot to test the aileron authority at the stall to see what effect those strakes might have.

The landing is normal for this kind of airplane. There are no flaps, so descent is managed by power and slipping. I used about 60 knots and had to carry a bit of power to keep the descent angle comfortable. There’s so much drag that with the throttle completely closed, you have to point the nose down quite a bit to maintain enough airspeed to fly and energy to flare. It slips very well, so I found that keeping a bit of power in hand and managing the descent with the rudder gave good results.

The landing gear easily absorbs less than perfect touchdowns and the bumps in rough grass, and directional control during the roll out is easy.

Reflecting on the airplane as the engine ticks and cools, it’s hard to see how it could have served the missionary role…it doesn’t carry much besides two people, it doesn’t have enough power to operate out of backwoods high-and-hot strips with a full load, and although the structure is simple and strong, it’s very labor-intensive to build. But it’s inexpensive to operate and easy to fly…something that will get you airborne on a quiet evening after the wind’s died down, let you open the window and smell the horse barns and backyard barbecues below, something you can ease gently onto a small strip of grass.

All the reasons your dad and uncle Bill loved that Champ…