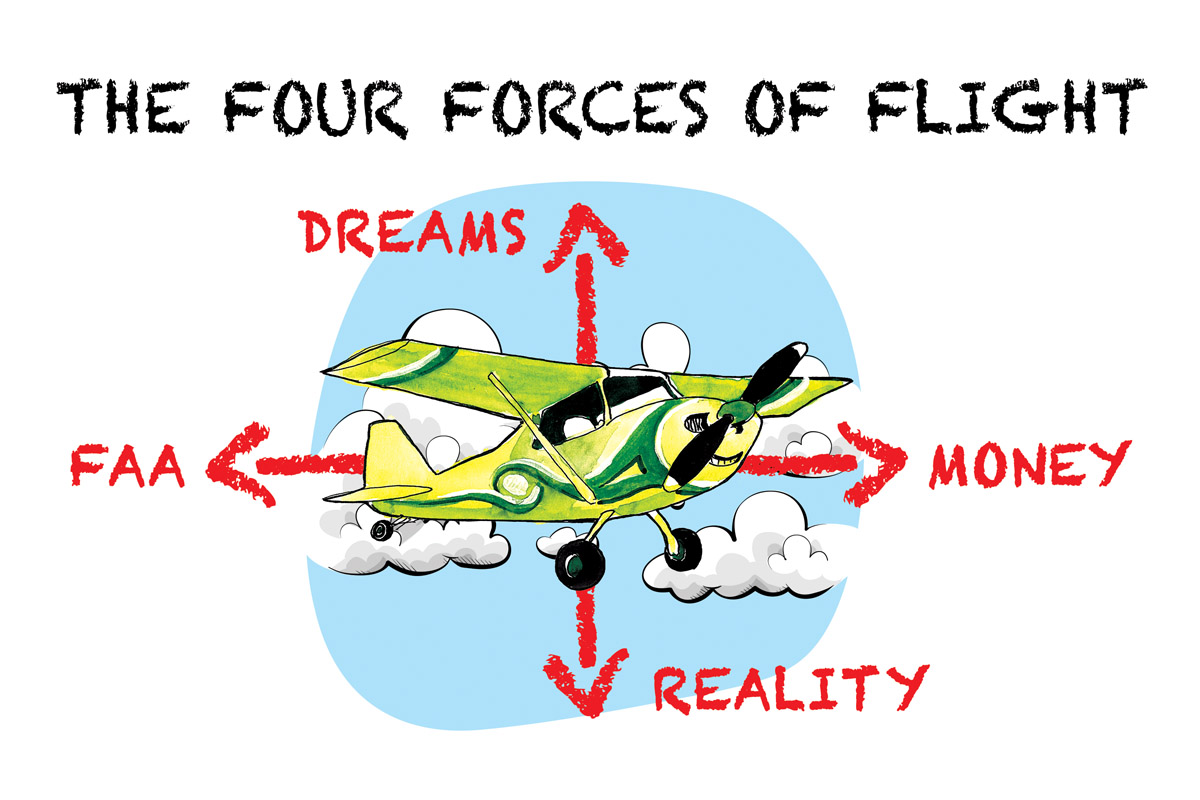

Somewhere in flight training we all came across that well-known graphic of the genero-plane with four arrows around it. “The Forces of Flight,” it’s typically titled and, of course, there is the obligatory “Thrust, Drag, Lift, and Gravity” called out. It’s all so neat and easy to understand, like curling up on the sofa and having NOVA take us on a precisely one-hour tour of Antarctica. Without so much discomfort as grabbing ice cubes from the freezer tray in that hour, we sense a complete understanding of the world’s under-curve, right down to how penguin rookeries must smell.

Usually we’re out of the flight school nest and into the more nuanced real world when we learn the actual forces acting on the pilot, if not the plane, are money, FAA, dreams, and reality. This realization is held in such high esteem it’s printed on T-shirts and paraded to the masses by people spending their own dollars to act in an educational capacity—a well-appreciated effort, for sure.

But after flying for a while, there comes the nagging suspicion there may be other forces in play. For some these other powers remain well in the background. People employed in deprecation of gravity for a living, especially those wearing uniforms in flight, are typically so cocooned by support structures such as ground crew, fuelers, dispatchers, and the comforting counsel of chief pilots and commanding officers that little time can be spent contemplating either the romance or physics of flight. They have a job to do, after all.

But for those of us either past getting paid to fly or having never had the chance, there comes a time when the new wears off, and the thought of tugging open the hangar doors and wheeling out the air buggy sounds, if not a little like work, then an activity not without effort.

“Where should I fly to?” becomes the question. Or more succinctly, “Why?” The weather is good, the evening winds calm, the day’s work done, and there you are with an airplane but maybe feeling a little tired and probably a bit guilty for it. After all, you invested all that time and money into the machine; your family sacrificed so you could justify that leather jacket, and now you’re having trouble coming up with the mental oomph to get down to the airport and commit some aviation. What would you tell Leonardo da Vinci or the Wright brothers should they be standing there? You’re not in the mood?

So there you are considering probably the most elemental force of flight: a reason to fly. I’ve found it about the most necessary item not on the checklist. It’s something that can slip away if you’re not careful.

The AOPA folks handling the Rusty Pilot seminars no doubt have more insight on this than anyone, but ultimately each of us has to identify their own motivation and recall it when the spirit flags. After all, has there ever been a time when you sort of pushed yourself to get up in the air and later thought it a bad idea? It’s rare.

If our flight motivations are personal, as plane builders and owners, there are forces working against our will to fly that are at least partially in our control. After 400 hours in a truly fun, but in some ways challenging, very homebuilt airplane, I’ve vowed that should I get the chance to rebuild my current mount or build a new plane, there are a few things I will more highly value.

First of these is comfort. I’m just as drawn to ground and aerial hot rods as ever, but after 45 years of squeezing, bending and literally aching for my fun, I’ve had it. If it hurts to sit in your plane, it can become a reason not to fly that day. If you’re contemplating building a certain design, make sure you fit first (fighters and racers are exempted)! And along those lines, at 6 feet 2 I’ve found it less than informative to speak to 6-foot-0-inch people about fit. Fractions of an inch count, as does wiggle room after wearing a five-point harness for 20 minutes. If you’re already building a plane, try to keep the totality of the finished cockpit in mind. Tacking stuff to the bottom of the panel is easy to do, but can be space-killing.

Baggage space has also moved up my list. Admittedly, I’m flying a tandem-seat, open-cockpit bird with room for a toothbrush if you zip-tie it to the engine’s oil fill tube—and yes, I’ve seen the owner of the sister plane to mine thread a banjo between his torso and the fuselage, then fly across two western states, but that’s not my tune. Small spaces add up, so if you can find a cubby, turn it into a storage locker. The boss put a pair of lockers in his RV-3’s engine cheeks, which frees the sparse interior from having to carry the oil rag and fuel checker, which, if nothing else, helps subdue the mechanical aroma in the cockpit and helps when headed over the horizon for a few days and you’re looking to squeeze in a banjo.

Side-by-side airplanes are usually not baggage challenged as their weight-and-balance characteristics favor steamer-trunk storage behind the front seats, but tandem ships are often lacking storage. Wing lockers, under-seat space, and (carefully considered) aft-fuselage access are a few solutions. Many pockets and sleeves around the cockpit help as well.

Serviceability is another will-do item for me. Many homebuilts, especially legacy designs assembled by die-hard fiscal fist clenchers, simply don’t account for having to maintain them. These cats use just enough to get the job done and can’t be bothered with niceties such as access panels. You know you’re going to lube control bearings, or at least want to eyeball them and their mounts for cracks, so why entomb them behind acres of doped Dacron? Next time I think I’ll put a zipper in the aft fuselage.

Even more common, there’s no savings in not building in ease of maintenance now. When the ignition switch failed on my bird, we quickly found—of course—there was no service loop in the wires, and it was nearly impossible to take the old switch out, much less install a new one. So all the wires were cut and a service loop installed. I wasn’t happy with introducing a bunch of new solder joints in my electrical system, and I shouldn’t have had to. The original builder should have put in enough wire for servicing.

Likewise, nutplates may knot your windsock when building, but lord, you’ll love them come the first condition inspection. Fumbling with little nuts and washers is for watchmakers.

Then there is the general environment around your plane. If the airport is 30 miles away…if the hangar doors are too heavy or balky…if you have to move two airplanes to get your airplane out…if it takes a half hour to uncover all the protective canvas over your sits-outside airplane each time you simply want to chase a sunset, you probably won’t chase it.

In short, if you’re building an airplane, my advice is to make it as user friendly as possible. If it costs a knot or two in speed, or horrors, makes a bump in the finish, that’s a small price for making something you’ll want to use, rather than force yourself to fly.

![]()

Tom Wilson

Pumping avgas and waxing flight school airplanes got Tom into general aviation in 1973, but the lure of racing cars and motorcycles sent him down a motor journalism career heavy on engines and racing. Today he still writes for peanuts and flies for fun.