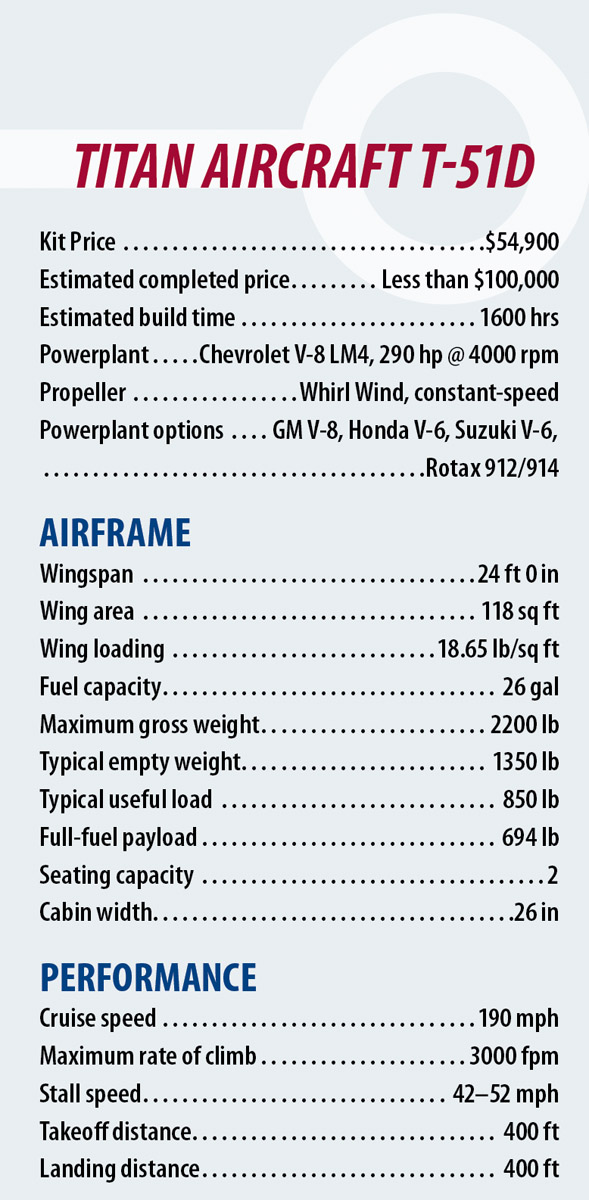

Bill Koleno is a master machinist, metal fabricator, and capable pilot who enjoys research and development and who fulfills all three of these roles while working at Titan Aircraft. At the tender age of 9, Bill considered himself a machinist, and by the age of 17 had built a gyrocopter in which he taught himself to fly. As an adult, he opened a machine shop where he fabricated parts and tooling for his customers who currently include General Motors, Chrysler, and Toyota, among others. In 2006 he joined the Titan team (while also keeping his shop running) and is currently working on the creation of a full-size P-51 replica to go alongside Titan’s popular T-51, a three-quarter-scale, all-aluminum P-51 Mustang available as a kit. The T-51 can be built as either a high-powered Experimental with retractable gear, or with fixed gear and a smaller engine, it fits into the Light Sport Aircraft (LSA) category.

John Williams is the mover and shaker of Titan Aircraft Company, which is located in Austinburg, Ohio, in the northeast corner of the state. The factory is a large, upscale facility housing John’s electronic controls business, along with the offices and production floor for the aircraft business. Titan is best known for the light and ultralight kit aircraft that have been in production for over 20 years.

Bill serendipitously met John by moving across the street from him in 2002. While house hunting, Bill’s wife liked the house down the road from John. Bill really didn’t care for the house, but he noticed that the “guy across the way” had a runway—so he decided he liked it after all. He then fixed it up the way he wanted it and met John as he was moving in. One of their neighbors asked Bill why he was building a barn, and when he told him it was so he could build a couple of airplanes, the neighbor said, “You’ve got to meet John.”

Bill’s gyrocopter infatuation was not short lived. Without plans and working only from photos, he copied Ken Brock’s early designs and powered his with a direct-drive Subaru engine. After logging about 1200 rotary-wing flight hours, he moved on to fixed-wing aircraft, starting with a Grumman Yankee.

John Williams also started early, getting his Private Pilot license at age 16. He flew certified aircraft for a long time before coming across the CGS Hawk, an ultralight-like Experimental sport plane that he really enjoyed flying. Seeing that CGS needed help with production, John joined the team in the 1980s and whet his appetite for building and designing light aircraft. No sooner did he get comfortable with the process then he designed his Titan Tornado, an ultralight that has a full aluminum cantilevered wing, steel-tube cockpit, and manages to fit into the very restrictive Part 103 ultralight category. This plane was the first of 13 similar Tornado designs, including several two-place tandem Experimental versions. Currently, there are only four models being offered by Titan, with either 24- or 26-foot wingspans. All are Sport Pilot qualified, and all are offered with a float option.

The Titan T-51

John always wanted a North American P-51D Mustang. In fact, there was a P-51 located at the field where John worked with CGS. But the going rate for a Mustang was way out of his price range, and the price has only grown exponentially with time. Realizing that he would probably never be able to afford a real Mustang, the decision was made to build a scaled version of his own. The issue was finding a reliable (and affordable) engine from which to design the aircraft around. Being a Rotax engine distributor through Titan, it seemed natural to try using the 65-hp Rotax 582, but being two-stroke, reliability was a concern. When Rotax came out with their four-stroke 912 engine, John was still apprehensive, but Rotax gave him an engine to test on his two-place Tornado that changed his mind. Fast forward to the present, and John says that the 100-hp four-stroke Rotax 912 S is as reliable as a Lycoming or Continental.

Back when engine decisions were being made for the T-51, Rotax stated they were working on a six-cylinder version that John was somewhat banking on upgrading to once it was well proven. But that never came to be. John wasn’t a fan of automobile conversions either, so that left him with few options; the time-proven horizontally-opposed certified engines just wouldn’t fit in the cowl.

To further drive home the anti-auto-engine-conversion attitude, one of John’s Canadian T-51 customers was unsuccessfully experimenting with different engines, starting with an inline four-cylinder turbocharged Suzuki engine that didn’t work, mostly due to the power-to-weight ratio being inferior to the 912. But then he moved up to a Suzuki 2.5-liter V-6 with a belted propeller speed reduction unit (PSRU) weighing in at 317 pounds and making about 160 hp. News of this installation made the circuit, and not long after, John’s customers started asking about it for their planes.

Still not willing to trust a one-off design, he asked the builder to let him know when he hit the 300-hour mark. Once notified, John hopped on an airliner to Calgary to fly that plane, full of preconceived notions that he’d hate it (just so he could objectively tell his customers that he knew firsthand that it was no good). But he found out otherwise once in the cockpit and behind the controls. According to John, “It did everything better; it doubled the climb rate, and it didn’t adversely affect the stall speed.”

A Suzuki V-6 powered Titan T-51 with a fixed-pitch propeller and fixed landing gear will meet the LSA minimums in a single-place configuration, with a full-throttle speed of 145 mph (not maximum continuous power—that’s limited to 138 mph for LSA) and a full-power climb of 2000 fpm.

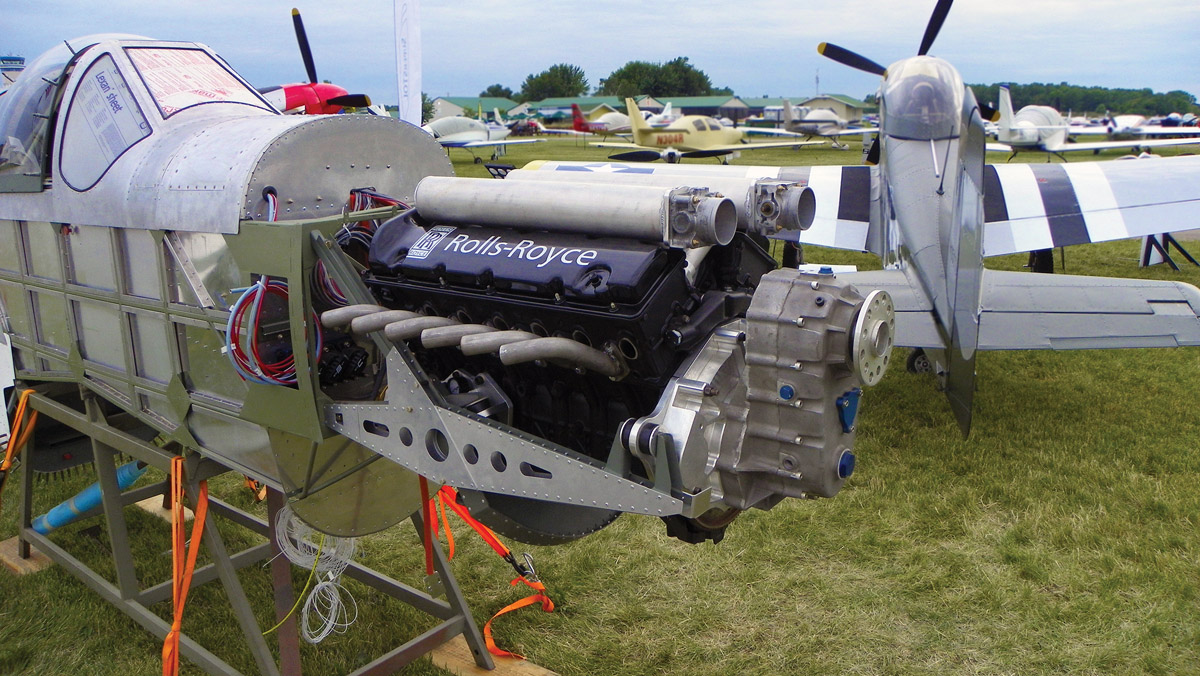

Back at the shop, John made the decision to install a copy of the Suzuki V-6 in an airframe they were prepping to receive an Innodyn turbine. He gave the engine the moniker “Mini Merlin,” but the belt drive proved to be problematic, so they moved on to the New Zealand-made Autoflight geared PSRU. Engineered for 300 horsepower with a 1.5 safety factor, it also allows the use of a constant-speed propeller. John tried a Honda V-6 as an upgrade from the Suzuki, but ultimately he landed on a Chevrolet V-8.

With the Autoflight PSRU, John says there were “zero teething pains and zero trouble” with the General Motors LM4 V-8 engine in the Titan T-51. The LM4 is the aluminum version of the LM7 that makes the same 290 hp but weighs 80 pounds less than its iron-blocked twin. With most auto conversions, the engine itself is usually bulletproof—it’s the systems and/or the PSRU that tend to fail. So with that, John and Bill elected to change the oil in the PSRU at 5 hours, then 10, then 20, and every 50 hours after that, and include a thorough inspection with a borescope. The PSRU is gear-driven and lubricated by splash from its own source, not engine oil, so oil analysis can spot trouble before it gets too far.

Even with a Dynon EFIS, Garmin avionics, and a few other modern instruments, the cockpit retains the look of a WW-II fighter.

The New V-8

Since the LM4 is no longer available as a long-block crate engine, the more powerful, 6.2-liter Chevy LS3 ($7,911 MSRP) will be the engine of choice for those wanting V-8 power in their T-51. The crate version of the 430-hp LS3 engine (restricted to 300 hp at 4000 rpm for the Titan T-51) is standard in the Chevrolet Corvette, Camaro, and the ill-fated SS, and comes complete from GM—from the oil pan to the ignition system. It also includes the composite EFI intake manifold assembly with injectors, fuel rail (returnless, multiport fuel injection) and throttle body, nodular steel exhaust manifolds, aluminum high-volume water pump, harmonic balancer, and a high-resolution 58x crank position sensor directing the high-energy solid-state direct-fire distributorless integrated ignition system with “coil near plug” architecture. It’s a very complete and compact package.

The LS3 is filled with components and features designed for high performance and longevity, including a 90-degree-cylinder-angle cast-aluminum block, forged crank (manual transmission version), forged rods, and hypereutectic aluminum pistons. The L92-type rectangular-port heads are cc’d for 10.7:1 compression ratio, and the hollow, high-lift hydraulic roller camshaft still uses traditional pushrods to actuate the roller rockers. The all-aluminum oil pan houses the dry-sump lubrication system that uses 8.9 quarts of oil.

All this adds up to be a lightweight, well-engineered, reliable powerplant. The LS3 6.2L engine delivers a great balance of performance and efficiency. In fact, the 2010 Corvette gets up to 26 mpg on the highway with the manual transmission. But the engine can’t take all the credit; the body has been reworked to reduce drag. Another key to the LS3’s efficiency is great airflow throughout. Intake flow was improved over previous engines by straightening out and optimizing the flow path from the intake manifold into the cylinder heads, while the exhaust ports are also designed for greater flow. An engine is just an air pump. The more efficiently it can pump air, the easier it can convert air/fuel into power.

Flying the Titan T-51D

Each year at Sun ‘n Fun in Lakeland, Florida, I typically begin my day in the ultralight area, commonly referred to as “Paradise City” and named for the 1989 Guns N’ Roses anthem of the same name. One of my regular visits is with the people of Titan Aircraft, which usually ends with an invitation to go flying in the latest iteration of the T-51. So far, I’ve had the pleasure to fly in the 100-hp Rotax 912 ULS version and both of the V-6 powered planes more than once, but during the 2016 show, I got to fly the V-8 powered T-51D. And at Oshkosh later that year, I flew the Rolls-Royce (BMW) V-12 Titan T-51B prototype.

While I’m qualified and potentially skilled enough to fly solo from the front seat, I felt far more comfortable with Bill in the front seat and PIC. Paradise City is a busy little uncontrolled grass strip with mosquito-like ultralights buzzing around with as many as 15-20 in the pattern at any given time. While they do keep the powered parachutes and trikes separate from the more traditionally configured (and faster) aircraft, a 200-mph high-performance plane like the T-51 just seems so out of place.

Each morning there’s a pilot’s briefing where the traffic pattern and proper procedures are conveyed, and each attending pilot leaves with a distinctively colored wristband for that day. In short, the faster planes fly a larger pattern than the slower ones do. There are also designated practice areas outside the pattern, and a predesignated pattern entry point. It’s all see and avoid, with no radio contact and certainly no control tower.

The back seat of the T-51 is rather small, and the ergonomics, while not impossible, are a bit unusual. It’s like you’re sitting in a dinner table chair, with your feet placed where they would go if you were sitting properly, but now shorten the legs by half but keep your feet planted where they are—then place rudder pedals flat on the floor under your feet. You operate the rudder by keeping your feet flat, and shuffling them fore and aft. While unnatural at first, it was easy to overcome and quickly became second nature. Keeping off the brakes while on the ground was a bit concerning, but again, not impossible. A nice pre-landing checklist item is to make sure the person in back isn’t inadvertently on the brakes.

In addition to being the fastest plane in the pattern by a factor of more than two (even when throttled back), the T-51 leaps off the ground after using less than a third of the tiny 1400-foot grass strip and transitions to a mostly vertical attitude with a nearly authentic-sounding exhaust note. It’s something to see from the ground, but is way more than an E-ticket ride from inside the cockpit!

Bill’s a big guy and a bit hard to see around, so nearly all my flying was done without the aid of any instruments. Engine rpm was easy to manage with sound, as was speed for the most part, but coordination was all seat-of-the-pants, with no view of the ball in sight. With the unusual rudder pedal configuration and the need to use rudder in turns (it’s not like an RV in that respect), I still found it rather intuitive to use the proper amount of rudder for each of the procedures we underwent.

hile the V-12 is literally pulled from a BMW motorcar, the Titan team found it fitting to add Rolls-Royce decals to the valve covers.

This wasn’t a “proper” flight program with flight test cards, checklists, and a predefined routine; it was more of a familiarization flight for my benefit that was conducted by a very experienced and capable PIC. We went through the usual procedures such as slow flight, steep turns, and recognition stalls—none of which were anything but what one would expect from a very well-behaved airplane. We even put the plane into steep climbs to show off the excess power. With the engine speed limited to under 4000 revs (peak hp is 430 at 5900 rpm and peak torque is 424 pound-feet at 4600 rpm), the sound wasn’t overwhelming. In fact at pattern speeds, we didn’t even need the intercom.

The engine does in fact have its radiator installed in the belly scoop—and there is a variable exit door, just like the full-sized P-51.

After about 30 minutes of exploring the performance and ability of this very well-mannered but exceedingly powerful airplane, we ended the free-flight portion of our excursion with a pair of traditional aileron rolls, one each way, the second one to unscrew my non-aerobatic inner ear. I say traditional as each time I’ve flown with Bill, this is what we did before heading back to the pattern.

The pilot briefing in the morning before each day’s flying includes procedures for high-speed passes, which the people on the ground love to see. Therefore, with the look of an authentic North American P-51 Mustang, and now with the sound that’s never been closer to the 12-cylinder Rolls-Royce Merlin 66 engine (the little Rotax never stood a chance!), it was time to show the crowd what this plane came to Sun ‘n Fun to do—and we did so with the smoke system on!

Once again in the very capable hands of PIC Bill Koleno, he slipped that incredible machine in for a textbook-perfect short-field landing, touching down squarely on his aiming point (just shy of midfield) before coming to a full stop within the advertised 400-foot range. Without missing a beat, he slid the canopy back as he whipped the tail around for a 180-degree taxi back to the staging area.

So now I’ve had a front row seat of the transformation of this little replica fighter aircraft. I’ve watched it grow from an eye-catching LSA to a fire-breathing, very capable, high-performance complex aircraft, and by far one of the finest scale replica fighters currently available to the kit aircraft market.

Rolls-Royce V-12 in a T-51B

A few months after flying the V-8 powered Titan T-51D at Sun ‘n Fun, I was offered the opportunity at AirVenture 2016 to fly the Titan T-51B (razorback version, like the P-51B) with a prototype Rolls-Royce (BMW) 5.4L V-12 engine—capable of 322 horsepower but limited to 300 for the T-51. While there was little detectable difference in speed and overall performance between the V-8 and V-12, the sound was perfect, and the uniqueness of the installation is absolutely marvelous.

One incredible feature of this engine and the way it’s set up and installed is that the dual redundant fuel system, intake system, and ignition systems are set up so that one side (bank) or the other can be completely shut off, turning the V-12 engine into a slant-6. Other than detecting a moderate power loss at cruise that can be easily recovered by adding in some throttle, there doesn’t seem to be a downside to setting this up as an economy cruise configuration. Switching from the left bank to the right and back again every 30 minutes or so (maybe even more frequently that that) helps keep the engine wear symmetrical.

The payoff is lower fuel consumption. It burns less fuel with only six cylinders firing, even though more throttle has to be used to produce the same power (thrust) as with all 12 cylinders firing, and it still remains silky smooth. I was surprised when Bill told me we’d be doing this, and even more amazed when we actually did it and I saw the fuel flow for myself.

Of course, this flight in the Rolls-Royce-powered B model ended in the traditional aileron rolls, but this time it was over Lake Winnebago, not Lakeland, Florida—big difference.

Titan plans to offer the Rolls engine option along with the Chevy LS3. They can be found at AirVenture at the far end of the homebuilder’s row, up against the taxiway that separates the warbirds from the homebuilts. That seems a fitting location for this beautiful scale replica—halfway between the warbirds and the homebuilts.