Grade A cotton and Irish linen, which were the only fabrics available for covering aircraft in the 1920s through the 1940s, are rarely used anymore. Synthetic fabrics have taken over the marketplace for covering steel tube, wooden and, in some cases, aluminum aircraft structures. It’s been over a quarter century since Grade A cotton was last produced in the United States. About the only place still producing it is England, and it’s very hard to locate. If you are lucky enough to find it, you soon learn that it’s very expensive to buy.

While Grade A cotton has a wonderful feel to it, has a dense weave, and is lightweight, it can be difficult to work with. John Norman found that out when he got around to covering the surfaces of his very precise replica of the Spirit of St. Louis. Though there are a number of Spirit replicas around today, most have opted to save time, money, and effort by using the longer lasting Poly-Fiber or some other variation on the theme of Dacron. Not John. He deferred to authenticity. By the way, Grade A cotton costs $26 per square meter, and Irish linen runs $47 per square meter.

The Process

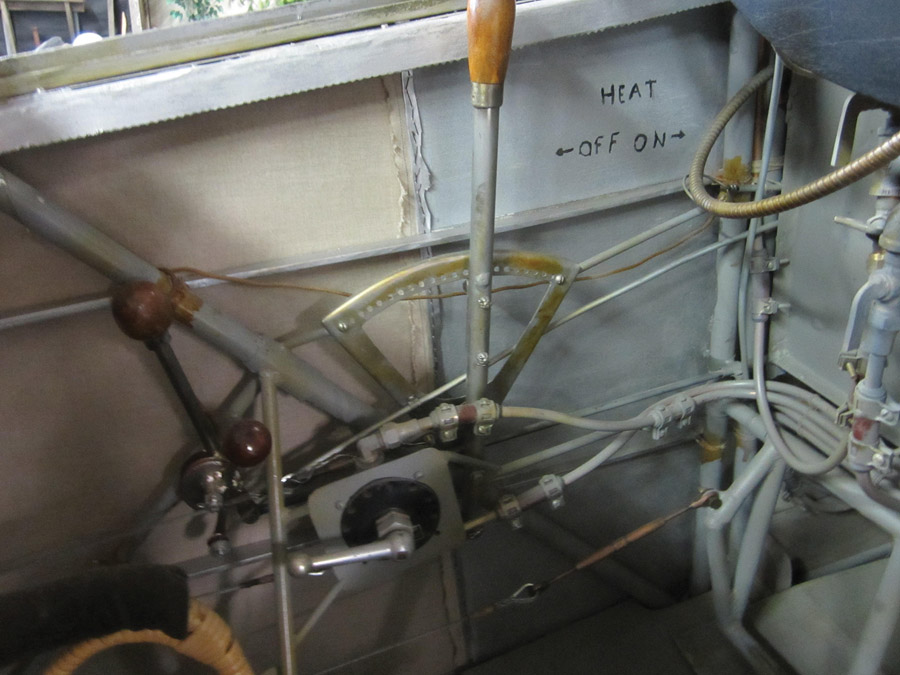

The first step in covering with either material is to get the fabric to adhere to the airframe. In the case of elevators or the rudder, Grade A cotton or Dacron gets glued directly to the metal frame surfaces. The fabric is wrapped around the metal. If one side is already covered, the other side is attached to the cotton or linen already in place using butyrate dope. The glue that holds cotton to metal will not hold fabric to fabric.

Working around corners is a challenge, requiring some carefully placed snips with shears and some pressing with a hot iron to get the glue to dry. The challenge is corners and rounded edges (elevators). Cotton won’t shrink with heat, Dacron will. So cotton requires careful cuts to assure a flat surface. Dacron can be shrunk with heat to assure a smooth surface. The Spirit project was John’s first experience with cotton, and there was a learning curve.

The principal difference between Grade A and Dacron, however, comes in the second step: shrinking the material so it tightens up against the surface of the frame. With Grade A and linen, the process requires wetting the surface of the material with water, then allowing it to dry thoroughly before applying dope. Dacron, on the other hand, can be tightened with an iron or heat gun. The response with Dacron is predictable. The Grade A shrink rate will vary with the age of the material, the way it has been stored, its prior exposure to humidity, and the humidity in the shop where the “wetting” takes place. Old fabric that’s been exposed to the elements or worked with in a shop that’s typically over 50% humidity will see the fabric tighten when moistened, but it will loosen up again once it dries.

John learned that the hard way. His first venture with the same type of material used on the original Spirit saw the cotton shrink up like a drumhead, only to relax and become floppy once it was completely dry. He tried applying dope, but the paint was over 15 years old and didn’t shrink the material. So, he tried newer dope. That brought better results, but once dry, it still wasn’t tight enough. John eventually realized that the fabric had been improperly stored for 25 years and was now worthless. It was an expensive, total loss. He acquired some new fabric and recovered an elevator with it, wetted it, and got a tight fit. He then applied new dope and it dried perfectly. John had learned that cotton bolts have a shelf life and so does dope. Having learned that lesson, he bought some cotton from a man in California who had owned it for some time, but had stored it properly so it behaved like it was supposed to. All of his old dope was replaced with new.

He has made a concession to history in avoiding nitrate dope, which was used on the original Spirit. It is highly flammable, so John opted for butyrate dope over nitrate.

John estimates that the original Spirit was given only four to five coats of paint, considerably less than most aircraft. “The fabric on the original Spirit is actually translucent,” said John. “But they didn’t bother with much paint because the airplane was only supposed to last for about 40 hours. Eventually Lindbergh put 480 hours on it, taking it way beyond what they were expecting at the time of construction.”

Seeing the Original

John had the rare privilege of being able to get up close to the original Spirit a number of years ago when they took it down for cleaning. He took a lot of measurements, photos, and video. In the process he got to look inside the original and was surprised to see that light was penetrating the covering. He also observed some long cracks in the fabric, where time has taken its toll on the fabric. He noticed that all of the original cotton string ties that held the wooden stringers in place on the fuselage have long since rotted out, and the fabric is the only thing holding them in place. The Smithsonian’s desire is to preserve as much of the original aircraft as possible, but barring any restoration activity, the Spirit of St. Louis is best described as “frail.”

At the time the original Spirit was built, nitrate dope was used for the first three to four coats. It penetrates the fabric better than butyrate, but nitrate is highly flammable, even when dry. During WW-I, when nitrate was used exclusively, a lot of pilots died when their planes caught fire. The burn rate is almost explosive, so John’s replica has no nitrate.

It took about 75 square meters of fabric to cover his replica. Some people are surprised to learn that the original Spirit fuselage is covered with Irish linen from just ahead of the trailing edge of the wing to the tail. The transition from cotton to linen is conspicuous when peering into the cockpit. So many people had cut out swatches of the fabric for souvenirs the night Lindy landed in Paris that they recovered it before moving it, and Irish linen was the only material available. The tapes that were used over the edges of the linen are cotton. Linen is a little coarser than Grade A cotton, a little heavier, and more difficult to work with, but it has the same life expectancy as cotton.

There is no chafing tape in the original Spirit, and John elected to leave it out of his copy.

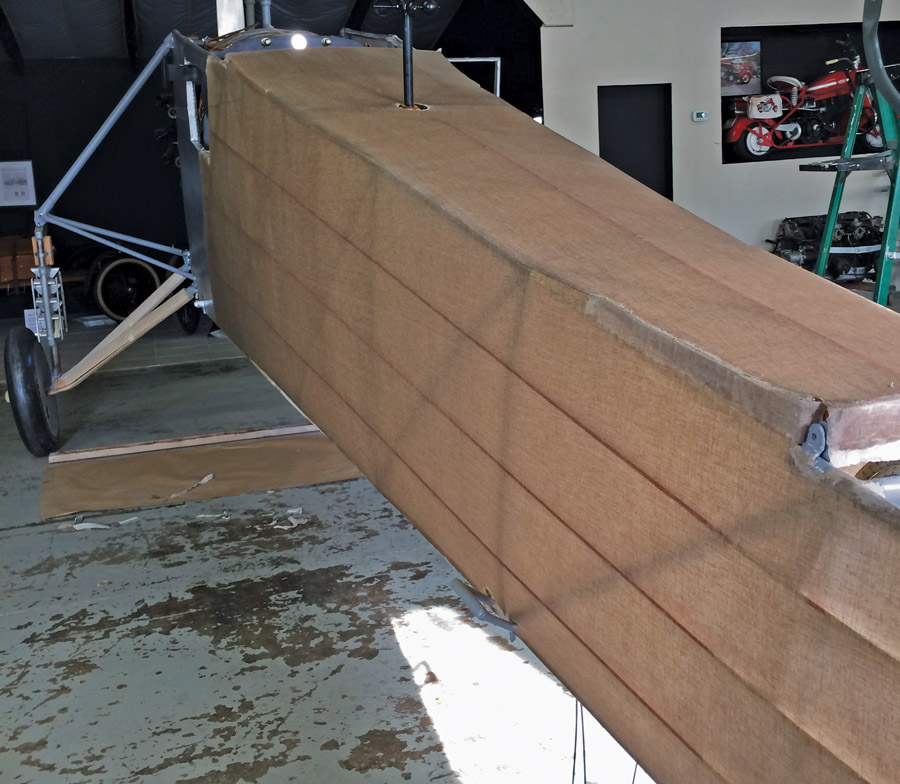

The 46-foot wings, which were not covered as this article went to press, will be covered as soon as the gas tanks are installed in each wing (at which time several ribs on each side will be cut away to make room for the two tanks). For that process, John will glue the fabric to the trailing edge and the leading edge before rotating the wing and gluing the cotton to the lower side of the trailing edge. The two edges of the material will be covered with cotton tape. The “envelope” for each wing is made up of pieces that were sewn together to provide for the full span of the wing.

John wound up recovering several components while he was learning how to handle cotton and linen. He also developed a profound appreciation for the ease of working with Dacron in the process. He estimated he was about a thousand hours from completion when last seen. If that works out, he’ll have over 6000 hours in construction when it flies. Flies? Where do you go to get dual in a copy of the Spirit of St. Louis?