Some amateur-built experimental aircraft have extremely short lives, especially if they are interesting old designs like the Davis DA-2, which first flew in 1966. Their resurrection is rare, especially if their pieces reside in baskets. But there are exceptions. Sitting in some shade at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, Dennis Hutchinson said, “I’m actually the fourth owner” of the Davis DA-2 tied down on the sunlit homebuilt flight line.

Now 66, when Hutchinson bought the airplane in 2014, he knew it would be his last. “My goal is to keep this thing until I can’t fly it anymore, and then it goes to my daughter and son-in-law.” Looking to that future, he restored the airplane for NextGen airspace, complete with ADS-B Out and In. “I don’t have to do anything for 2020.”

It doesn’t look very big, he said, but the cockpit is 41 inches wide, “the same as a Cessna 172.” Charles Young of Victoria, Texas, built and first flew it in 1995. “He’s in his 80s now,” said Hutchinson. “He still lives at the same address on the data plate. His workmanship was phenomenal.” Every aluminum edge is properly rounded and rivet lines cross wrinkle-free skins with regimental precision.

“He was thrilled to learn that it was still flying. He figured it went to the scrap heap years ago, and it sure looks better than the last time he saw it” in 2003, said Hutchinson. That’s when Young sold it—for cash—to a pilot from Port Aransas, Texas. “He wrecked it before he got away from the airport. The Davis flies like a Cherokee 140, with light, sensitive controls,” said Hutchinson.

Apparently, the second owner had only flown a Cessna 150. “He got hit with a gust, overcontrolled, and basically flew it smack into the runway from 10 or 15 feet.” The impact snapped the prop, bent the Continental O-200’s crankshaft, folded the nose gear, crumpled the right wing, and collapsed the right main landing gear.

In 2009, the Davis’ third owners, Mike and Jason Dick, a father and son from Minneapolis, bought the untouched baskets. “They reskinned the wing and did most of the structural repairs on it,” said Hutchinson, “and they had the O-200 rebuilt and pickled.”

Hutchinson did most of the work in his hangar at Indianapolis Regional Airport (MQJ) in Greenfield, Indiana.

Doing most of the work, Jason moved the project to Mankato, Minnesota, and his new job. Shortly thereafter, his family doubled in size. With four kids under 7 and his father a 250-mile round-trip away, they decided to sell the airplane, said Hutchinson.

Hutchinson was looking for an airplane because he’d sold the Zenith 601 HD he’d built with a partner in 2009. In it, he’d earned his sport pilot certificate and logged 535 happy hours. Looking for another sport pilot-eligible homebuilt, he settled for three out of four requirements when he found the Davis DA-2 on Barnstormers.com in November 2014.

He was familiar with the DA-2, and it met the sport pilot limits for seats, weight, and maximum speed. However, it missed on the 45-knot stall speed, so he needed to add an airplane rating to his private glider ticket. The hard part was finding a CFI and examiner who weighed 170 pounds or less.

Bringing it Home

To get the Davis’ two big, unwieldy pieces to his Greenfield, Indiana, home, Hutchinson rented a Penske truck for the one-way journey in February 2015. Loading the truck at 15 F was miserable, he said. Tied to the sidewall, he padded the one-piece constant-chord Clark Y wing with blankets. He restrained the fuselage with straps screwed into the Penske’s wooden floor. “With its engine on it, the extra weight kept it from rocking around.”

Original plans accompanied the airplane, and Davis drew many of them full scale. One of the drawings is 14.5 feet long. A CAD tech who started his career at an engineering firm as a draftsman, Hutchinson reads plans for a living. “I’ve seen better, but his ain’t bad. Considering the era, Davis was miles ahead of his homebuilt peers.”

The Dicks had completed most of the structural repairs, so Hutchinson planned on reassembly followed by flight. But making improvements when it was in pieces was easy, and one thing led to another, he said, and two years disappeared.

“I didn’t like the table-saw wing tips,” so he built 8.5-inch extensions with 45-degree tips that gave him room for strobes. Riveted to the outside rib at the back edge, “I’ve got a removable piece, so you can reach the bolt to remove the aileron,” he said. “There’s another plate on the inboard end, so you can get to that bolt.”

The Davis DA-2 sports a Dynon SkyView Touch system that includes ADS-B Out and In. The iPad runs ForeFlight.

The Davis’ wheel pants are unique. On the Wittman gear, he could have installed “sleek and sexy fiberglass wheel pants, but they wouldn’t fit the airplane,” so Hutchinson built three “miniature fuselages” that reflect the airplane’s flat, angular features. In total, his wheel pants weigh 75 ounces, “just a hair more than one fiberglass wheel pant.” Chuckling, he added, “On radar, I’m a flight of four.”

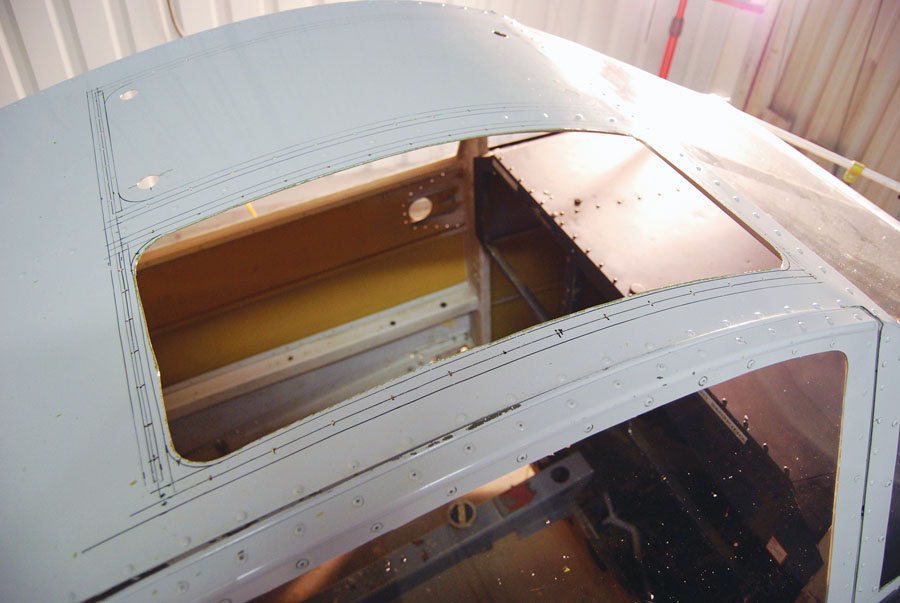

In his Zenith, “I got used to flying in a fishbowl.” With its roof, the Davis “was like flying a pillbox, so I put in a skylight” on either side of the steel frame. Now the pilot’s field of view is very good in all directions.

In creating the skylight, Hutchinson discovered polyisocyanurate insulation. Also known as PIR, polyiso, and ISO, he learned from a 2011 study by the University of Central Lancashire’s Centre for Fire and Hazard Science that the rigid thermoplastic releases toxic vapors, including hydrogen cyanide, when it burns. So he gutted the cockpit.

For its new upholstery, Hutchinson turned to the airplane’s future fifth owners, his daughter Deirdre and her husband, George Olszewski, a Michigan National Guard helicopter pilot. “I told them to make sure they do something they can live with.”

Flying is a family legacy. Hutchinson’s father Dick “joined the Central Indiana Soaring Club in 1960, when I was 8, and he was an active member” until six weeks before he succumbed to cancer in 2014.

Spending his childhood at the airport, while others were putting away the gliders, Hutchinson said he got maybe 30 hours in the front seat of this couple’s Cub before his first official lesson. He soloed a glider at 14, on his 13th flight, and “I had my private glider ticket at 15, before I had a driver’s license.”

His daughter is not yet a pilot, but they have many happy hours together. “Our last big daddy/daughter outing, before she married George,” was a three-day tour around Lake Michigan with 13 other airplanes.

Hutchinson’s father passed shortly after he bought the Davis, and his inheritance made the airplane’s complete restoration possible. “In light of that, it is only fitting to keep the plane in the family for as long as possible.”

Panel, Power, and Paint

With the cockpit gutted, Hutchinson replaced all the wiring. “It was old, and with all the electronic stuff I was putting in, and the LED landing and position lights, it was just easier to start from scratch.”

The same logic replaced the steam-gauge panel and ADF avionics with a complete Dynon system built around the SkyView Touch. To the right of the control heads for the communication radio, intercom, and two-axis autopilot, is a dock for his iPad. “I kick myself for not putting a 7-inch Dynon over there” because the iPad, which runs ForeFlight, is sometimes not bright enough.

But it is cool, thanks to the $9 PC cooling fan Hutchinson mounted behind the dock. Removing the iPad after every flight, cockpit peekers think it’s air conditioning. Unlike its kneeboard mount in the Zenith, his iPad hasn’t had a single overheated crash in the dock.

Hutchinson installed the avionics himself, but “I didn’t want to take the chance of putting a pin in the wrong place and ending up with $15,000 of magic smoke, so I paid SteinAir $400 to build the wiring harness, and it was worth every penny!”

Only “partially literate when it comes to avionics,” he said the massive Dynon installation and user documentation provided easy-to-find answers. He didn’t have to call the Dynon support line once. “Connecting all the sensors was a pain in the butt,” however. It wasn’t hard; just “pull off the Continental sensor and replace it with the smaller digital Dynon sensor,” but there were a lot of them.

With EGT and CHT on all four cylinders, oil temp and pressure, fuel flow and pressure, among others, carburetor inlet temperature is Hutchinson’s favorite. He only applies carb heat when the inlet temp calls for it. “Why throw away 10 horsepower when it’s nowhere near icing? At this time of year, when it’s in the 70s and 80s, the carb’s running about 60.”

The wheel pants mimic the angular, flat surfaces of the fuselage. Combined, all three wheel pants weigh less than one sleek, sexy fiberglass pant.

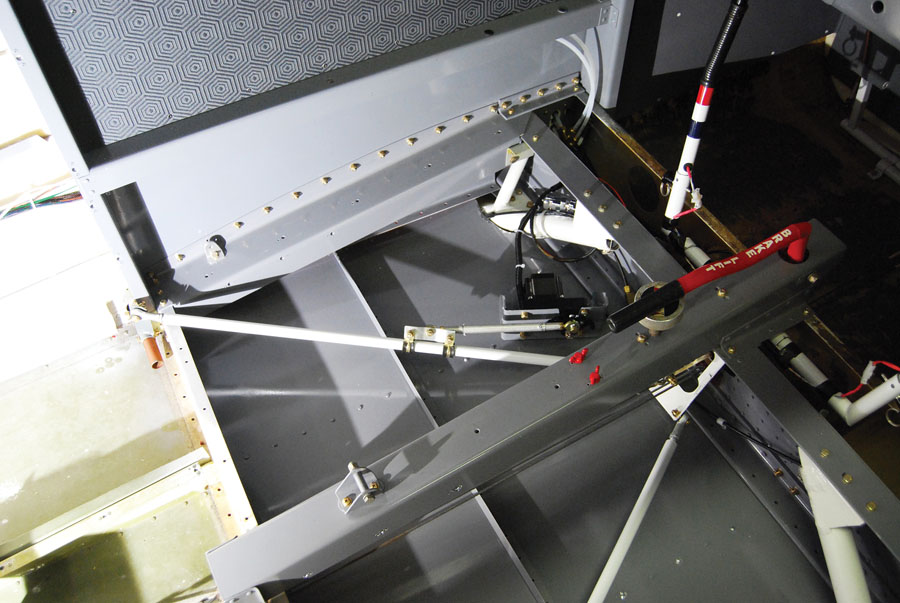

Making all the connections when he reunited the wing and fuselage was the project’s greatest challenge. “Unwieldy” best describes the fuselage with its nose wheel, and the one-piece wing with its main landing gear. And all the wires retreated to hard-to-reach recesses.

After logging 100 hours, cylinder one’s exhaust valve started leaking. Pulling the cylinder, he found thumbnail-sized valve seat erosion. “I tried to fix it, but it still wheezed like Darth Vader on a bad day.” After sandblasting the cylinder, the repair station found an unfixable crack connecting the erosion and spark plug port, so he bought a brand new cylinder.

Three hours later, during the annual condition inspection, “pulling just a 65,” a compression test revealed an exhaust valve leak in number three, “and the two on the other side were only pulling 70,” Hutchinson explained. “They were already broken in, so they should have been pulling better than that.”

The O-200 had been rebuilt with reconditioned cylinders, “so I had no idea how old or how many hours were on them,” Hutchinson said, so he replaced them with new cylinders. “It was a chunk of change, but the peace of mind is worth the money, especially in an airplane with the glide ratio of a manhole cover.”

With one thing leading to another, he stepped up to a Sky-Tec starter, a B&C 30-amp stator, and E-MAG electronic ignition. “That allows me to use automotive plugs, which have a lot more spark power than aviation plugs, and they are a lot cheaper.” An Aerovoltz lithium battery provides the initial spark. The small, 3.5-pound cube “has more cranking power than the battery in my car.”

Given the airplane’s small size, Hutchinson devised a paint scheme that enhanced its visibility. Speaking from experience, he said sailplanes are white to protect their composite structures, but those with contrasting paint on the nose and wing tips are easier to spot in flight.

He chose the colors “because I like them.” The red wing tips contrast with the white inboard wings, and the V-tail copies this. “The white upper fuselage stands out against the earth when viewed from above, and the red lower half stands out against the sky when seen from below. The gold and blue stripes are purely aesthetic.”

A local body shop applied the Limco automotive urethane base and clear coat. The flashing and wig-wagging AeroLED lights add to the airplane’s visibility, Hutchinson said. “Friends have told me that the plane is lit up like a Christmas tree.”

Flying a Freeze-Dried Bonanza

Installing an oil-air separator was a good, timesaving decision, especially while breaking in the new cylinders. “I’m 66 and still relatively spry,” Hutchinson said, but cleaning the belly is an uncomfortable chore.

And that’s why he often flies from the right seat. “There are a lot of things about the Davis that are almost identical to the Cherokee 140, but the door size isn’t one of them. Getting in and out of a Cherokee is a lot easier.”

The Davis’ sticks don’t make the slide from right to left any easier. Between the seats is the brake lever. “It’s hinged backwards, so it’s kinda weird the first time you use it, but it’s a natural motion and I like it.” The rudder pedals control the steerable nose wheel.

The wing has no flaps or washout, Hutchinson said, so it stalls all at once. There’s no buffet because the V-tail is in clean air. The only cue is the steep deck angle. “When it goes, it just quits flying.”

Stalls in uncoordinated flight are “aggressive,” he said. “My 601 didn’t have flaps, and I used to skid it a bit when turning from base to final to lose a bit more altitude. I tried that—at altitude—in the Davis, and that was the last time I did that. I’ve got AOA [angle of attack] on the Dynon, and I watch it like a hawk” in the pattern.

Tapped into the Davis Yahoo! group, Hutchinson improved the stall characteristics with vortex generators (VGs) on the wing and underside of the V-tail. That lowered the stall speed to 48 knots and gave him aileron control throughout the stall, “and it actually has a bit of a [pre-stall] buffet now.”

His target speeds are 90 knots on downwind, 80 on base, and 70 slowing to 65 on short final. “If you need to come down in a hurry, slow to 65 and suck the power out of it, and the Davis will come down at 1100 feet a minute.” Although the plane trues out at 115 knots while burning 6 gph, Hutchinson often cruises at 2500 rpm, which yields about 100 knots indicated while sipping just 4.8 gph.

Watching airplanes make their way around the Oshkosh fly-by pattern, Hutchinson said, “I’m having a blast with the airplane. It’s fun and easy to fly.” And, as it has at Oshkosh, the Davis DA-2 attracts attention wherever he goes. “People always ask, ‘What is it?’ And my answer—a freeze-dried Bonanza.”

For more information, visit D2 Aircraft, LLC at www.DavisDA2.com.

Just a quick note to say that I knew Leeon Davis in the late 1960s when we both worked at Windecker Research, Inc. in Midland, TX, where we built and obtained the type certificate for the first all-composite powered airplane, the Windecker Eagle. Leeon was a mechanic and I was Chief Inspector, so we had quite a few dealings with one another. I was in the process of building my first homebuilt airplane and Leeon helped with advice. I always liked him and admired his DA-2A design.

I have loved that litle airplane since i got a ride in one back in the 80’s. What a simple concept to build, simple tpo own, simple to fly, and for it’s HP and weight it’s a fast little plane. This was a great article to read also. Great job on the article Scott!!!