Homebuilt aircraft have gained serious traction in the GA market the past several years, and there are plenty of reasons for that. If you’re reading KITPLANES®, you already have your own reasons. For the most part, builders and pilots treat them just like certified aircraft—only better. But the truth is that kitbuilt aircraft present insurance underwriters with unique challenges.

Homebuilt aircraft have gained serious traction in the GA market the past several years, and there are plenty of reasons for that. If you’re reading KITPLANES®, you already have your own reasons. For the most part, builders and pilots treat them just like certified aircraft—only better. But the truth is that kitbuilt aircraft present insurance underwriters with unique challenges.

Certified airplanes, at least right after they come off the assembly line, are all pretty much the same. There are styling and equipment options, but the airframe and most of the systems are the same for a given model. And one of the mainstays of insurance is the grouping together of homogeneous units. Given a substantial number of essentially the same aircraft, insurers can predict their loss cost. At the end of the year, they can look at their claims and adjust rates accordingly. That’s not so easy for homebuilts. So what does all of this mean for the new homebuilder or new owner of a used one? We did some research to find out.

Versus Certified

The different types of kitbuilt aircraft seem to blossom in endless profusion. According to a recently revised FAA list of kits that are available, there are more than 200 offerings, depending on how you count. A large part of the kitbuilt fleet is made up of two dozen types of aircraft, but insurers are still faced with many more types of kitbuilt aircraft than factory-built aircraft. There are literally hundreds of types to choose from.

Another difference: Certified aircraft are built in factories with the factory’s name etched on the data plate of each aircraft. Most certified aircraft manufacturers carry aerospace products liability insurance. Aircraft insurers frequently bring manufacturers into accident litigation if there is any hint of product liability. By contrast, amateur-built aircraft proudly carry the name of the individual who built them, and he or she may not have millions of bucks to defend a product liability suit. Moreover, the insurance company may not be able to count on the airframe manufacturer’s insurance to share the burden.

Physical damage claims may also be slightly more involved for homebuilts. Some obscure types or types whose kit manufacturer is no longer in business can be difficult to get parts for. Total losses are straightforward, but partial-loss claims may require more work for the adjuster and the owner. Many maintenance shops are hesitant to work on a type of aircraft they are unfamiliar with, and where there is no product liability backstop, as there would be in the case of a certified craft. In the case of a partial loss, the owner may want to make his own repairs. Together, the insurer and insured come up with a value for the airplane as it sits, and then work out an hourly rate for the owner’s labor.

Liability Issues

Liability claims against the aircraft owner are also straight-up propositions. The aircraft owner is probably the manufacturer if he built it, as well as the maintainer and the pilot. Since almost all amateur-built aircraft policies are written with per-passenger or even per-person sub limits of $100,000 per passenger, in some cases $200,000, the insurers pay these limits fairly promptly, both to fulfill their contractual obligation to their client and in order to avoid bad faith claims charges. Although the owner may benefit from the insurer paying for the cost of defense, this too will probably end once the company has offered to pay its limit of liability.

This is not unique to kitbuilt aircraft, but owners of certified aircraft often have the opportunity to buy out the per-person or per-passenger limits and purchase what insurance people refer to as “smooth” coverage. Smooth limits allow the insurer to pay liability claims for bodily injury and property damage in whatever amounts are needed until the limit has been exhausted. This is more likely to be sufficient to take care of injured passengers, and the insured also benefits from having the costs of defense for a longer time, perhaps all the way to settlement. If the insurance company has more at stake, they are more likely to mount a defense than if they only had $100,000 or $200,000 at stake. In our conversations with underwriters, we came away with the impression that “smooth” coverage was very difficult to obtain for kitbuilt aircraft.

Among people that we spoke with about the world of Experimental/Amateur-Built aircraft, there was almost universal agreement that these aircraft suffered a higher rate of accidents than their certified brethren. Just how much higher is very much a matter of debate. It’s not that there are not any statistics; it is more that the statistics are measuring different things. The FAA only looks at fatal accidents when it looks at homebuilt aircraft. Insurers and those within the homebuilt community who keep track of these things look hard to find all the accidents. And there is nearly universal agreement that homebuilt accident rates in general are higher than those for certified aircraft, but are continuing a long downward trend.

And kitbuilt aircraft have one area of risk that certified aircraft do not: Exposure in Phase I flight testing. Whether that’s a 25- or 40-hour program, this process, including first flight and subsequent flight testing, is just not part of an owner’s experience with a Cirrus or a Piper. Consider that 13% of all kitbuilt accidents happen during this fly-off period, most of them during the first 10 hours.

Apples and Apples

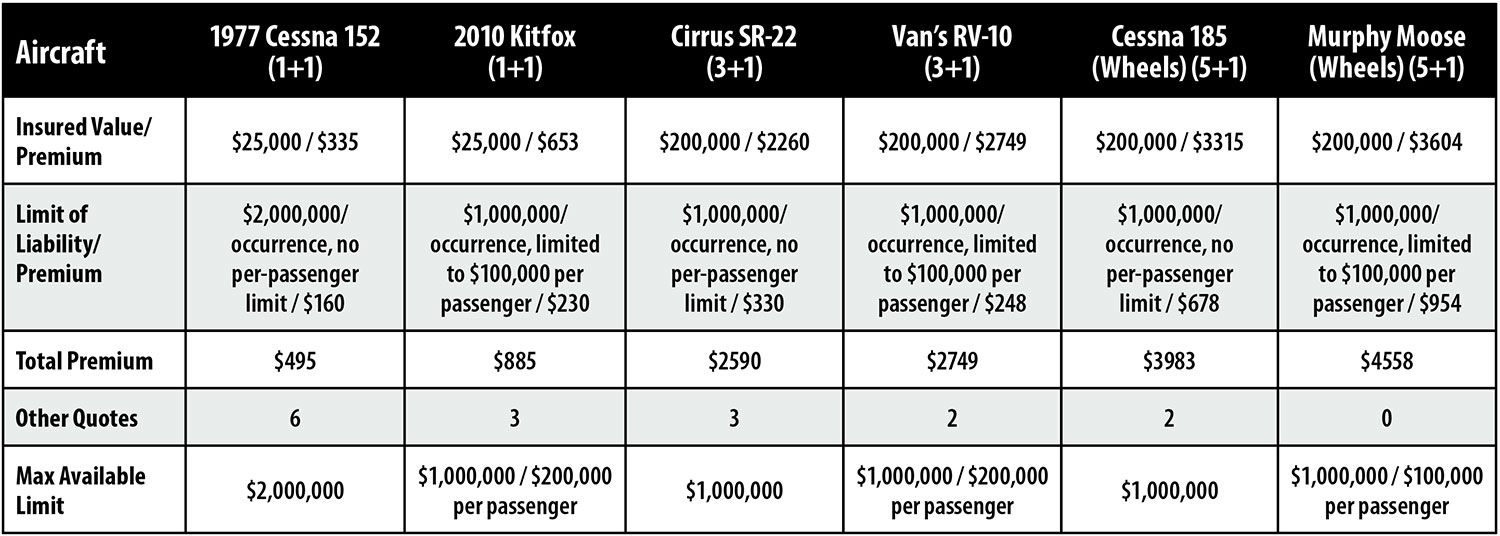

In order to get a better feel for how much these higher claims activities cost owners when they buy insurance and how available insurance is for these aircraft, we set up a comparison between three certified airplanes and three homebuilts—for identically qualified pilots. We chose pairs of two-, four- and six-seat airplanes. There are relatively few four-seat kitbuilt airplanes and even fewer with six seats. We were surprised by some of the results, which are shown in Table 1 above.

We took the most competitive quotes in each category, so they did not all come from the same insurer. We also showed the number of quotes that we received for each airplane and the highest limit of liability that we could get for each airplane. Apart from price, the availability of insurance, expressed as the number of successful quotes, and limit of liability are key measures of how likely you can successfully buy insurance for each type. Note that we made our sample pilots very qualified in order to encourage successful outcomes. The numbers in Table 1 should be viewed as indices, rather than as insurance quotes. They are more predictors of whether or not you can find insurance than precise measures of what the insurance will cost.

While some of the numbers here are surprising, some are not. It is still easier to find a variety of insurance offerings for a certified airplane than a kitbuilt one, and you can more often get a higher limit of liability for a certified airplane. For the most part, the highest limit of liability that is available in the market for kitbuilt aircraft is $1,000,000 combined single limit, subject to a maximum of $200,000 per passenger or per person. Many will limit bodily injury coverage to $100,000, depending on the pilot’s experience or the type of aircraft.

Here are some things to think about if you are considering getting involved with a kitbuilt aircraft:

- Does the aircraft that you are looking at have a substantial owner’s group that can help you with questions as you go?

- Will you be able to get parts easily for this airplane once it is built?

- Can you get along with a sublimit of $100,000/person to $200,000/person on your insurance policy for bodily injury and property damage? In the current fraught insurance market, make sure you can obtain the limit that you feel you need.

- Don’t wait until you have a completed aircraft to purchase aircraft insurance. Insurers like long relationships with their clients. You may have to reserve an N-number, but your insurance company or broker can give you valuable advice along the way. And each kit portion that you have purchased has value, so by the time you are well into the project and have an engine or some radios, that value is considerable.

- Make a plan for first flight. If you don’t, your insurance company may do it for you. Are you already a pilot? Do you have experience in the type you are building? In order to make the first flight and test flight period safer, the EAA and the FAA and the manufacturers have provided resources for builders like the EAA Technical Counselor and Flight Advisor programs. If you don’t have any experience in the type of aircraft you are building, does it make more sense to hire a professional for the first flight or to do it yourself? Again, if you ask the question before you ask your insurance company, it will let them know that you have considered the issue.

Before you cross any bridges, have a conversation with your insurance provider. They will appreciate being included, and they can probably give you good advice.

Photos: Shutterstock, Paul Bertorelli, courtesy of Cirrus.

list please of insurance companies for experienced pilot [atp] 78 yeaars

no accidents- waivers – declinations or violations