Flying an RV-8 from Los Angeles, California to Oxfordshire, England in 19 days may strike many as an adventure of a lifetime. For me, the 7000-n.m. trip was my way to return home after working four years in the Tesla Motors Design Studio in Hawthorne, California. Airfields along the Crimson Route, partially developed in WW-II as a way from North America across Greenland and Iceland to Britain and the European theater, would provide the critical fuel stops to complete my journey. These WW-II fields are now civilian airports and provide a route for shorter-range aircraft crossing the northern Atlantic while avoiding a high-frequency radio requirement. With this trip in mind for a couple of years, I bought a more versatile RV-8 to replace my previous RV-4.

Planning the Trip

Pre-trip planning largely focused on two concerns: fuel planning and preparing to deal with arctic weather. Historically, bad weather and poor fuel planning claim many more victims than mechanical failures across this route.

The crossing of Greenland from west to east over the icecap presented the biggest challenge and most critical leg for fuel planning purposes. There was only one usable airfield on my planned 380-n.m. route across eastern Greenland, and a diversion to the next-closest field would add another 350 n.m. to the trip. Adding contingencies for winds and IFR reserves, I settled on a planned minimum endurance of 7 hours at 150 KTAS to give me a comfortable safety margin. In principle, the 42-gallon standard fuel capacity of the RV-8 would be okay, but to build in my “comfort factor,” I added a 10-gallon fuel cell in the front locker. I discussed this approach with Jon Johanson (noted for his world-rounding RV-4 trips), and he agreed with my plan to plumb the cell directly into the spare inlet of the Van’s fuel valve and vent it at the bottom of the firewall.

The most valuable planning came by reading reports and talking with several people who had been that way before. The overwhelming emphasis? Don’t take chances with the weather, carry sufficient fuel for all contingencies, and make sure everything is working properly before heading for the Arctic! Obviously, avoiding known icing conditions is a big part of weather planning for a small aircraft.

Prelude—Crossing the USA

The journey started for real on Monday, April 8, 2013. My apartment was empty and the keys handed back to the landlord. The aircraft was loaded and car delivered. Fellow RV pilot, Scott Chestnut, picked me up and delivered me to the Hawthorne airport.

Reports of strong, gusty conditions (common over the Southwest’s desert in spring) populated the METARs. Checking the PIREPs, I abandoned my plan for lunch at Sedona, Arizona, and re-filed for Carlsbad, New Mexico. The extended distance (720 n.m.) provided a good checkout of all systems, including the full auxiliary tank. After climbing to 15,000 feet, an amazing 85-kt tailwind from the west pushed my groundspeeds up to 240 knots. Arriving in Carlsbad, the winds were still strong and confirmed the wisdom of selecting this airport with four wide, WW-II-era runways providing six potential landing directions. Thanks to the tailwinds, I arrived in about 3.7 hours and only used 26 gallons.

The original WW-II Crimson Route followed a great-circle path out of Los Angeles and up into northern Canada. I, however, planned my transcontinental travel to put me in Florida for Sun ‘n Fun, then up the east coast into Canada. Therefore, I continued from Carlsbad to Denton, Texas. The first day covered over 1000 n.m. and ended with a hangar for the plane and a room offered by fellow RV pilot, Russ Madden, through Vansairforce.net’s “RV Hotel” list. It was a good start to the journey.

I made my next overnight stop with Mike and Judy Ballard in Lanett, Alabama. Two years earlier, I had persuaded the Ballards to sell their beautiful RV-8, N713MB, to me so the stop was a homecoming for the plane. During the stop, we also sorted out a Bluetooth connection issue with the brand-new Delorme InReach satellite tracker. After confirming that tracking, email, and text messages through my iPad worked in flight, we spent much time talking about the trip. I knew they would be tracking my progress on the Delorme web site all the way home.

A relatively short run in good weather, with a quiet Lake Parker arrival the next morning, brought me to Sun ‘n Fun. Mary Jane Smith greeted me with a big hug once I shut down the engine. Regulars at Homebuilt Camping will know what I mean. It’s like coming home when you arrive—a great bunch of people gather each year in HBC.

Sun ‘n Fun provided a nice break and good opportunity to catch up with old friends. News of my trip preceded me and regularly popped up as a topic of conversation. My aircraft had been featured on this year’s SNF poster, and their photographer took photos of the poster, me, and the plane, adding them to their Facebook feed. I also was asked to sign several copies of the poster. I guess this is what it’s like to be famous!

A good opening between a series of frontal systems along the East Coast presented itself on Sunday, nicely coinciding with my planned departure. I had a good run up to St. Simons Island, Georgia. With weather catching up, I made a quick refuel and continued up to First Flight Airport at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, for the obligatory photo with the Wright Brothers National Memorial behind. After a quick tour of the site and museum, and a late lunch, I made a short hop to Williamsburg, Virginia for the night stop and a visit to Colonial Williamsburg.

The next leg took me to Bangor, Maine. Passing through New York City, I dropped down to 1200 feet and routed into the Hudson River Corridor by the Verrazano Bridge. Aimed for the east bank, I kept busy taking photos, making reports, and swivelling my head for traffic. Assorted alerts for obstacles, terrain, and traffic flowed from the Garmin 695 and GTX330 transponder’s Traffic Information Service (TIS) through the intercom, while I shouted, “I know, I know!” which didn’t help much.

I passed Boston just after the dreadful marathon bombing, unaware of the events unfolding on the ground. Then, with Bangor less than 100 miles away, a change in exhaust tone, followed shortly by a CO alarm, grabbed my attention. Closing the heater and opening the cabin vent, I alerted Center to the situation and picked Sanford, Maine as a close and promising diversion. Exhaust backfiring accompanying the power reduction seemed to confirm a likely exhaust leak.

The next morning, it became apparent that the #2 exhaust stack had failed just below the pipe-to-flange weld. Discussing this failure and the impending trip with a local mechanic, we decided to overnight the stack to Clint Busenitz at Vetterman Exhaust in South Dakota for repair and reinforcement with extra gussets. Southern Maine Aviation couldn’t have been more helpful, letting me use the crew car for three days. The Maine coast wasn’t the worst place in the world to be stranded, and the lobster was delicious. Kennebunk and Ogunquit were rather quiet this early in the season, but it was a pleasant area to pass some time. The repaired stack arrived back on Friday and was quickly replaced, allowing me to finally continue to Bangor.

I stopped overnight at Bangor to get the paperwork sorted with the brokers for exporting the RV. My next planned stop was to be Sept-Îles, Quebec, but the delay meant that CANPASS (Canada Border Services Agency’s program for clearing border crossings) wouldn’t be available there on the weekends. So, I re-planned for Moncton, New Brunswick, filed with Canada’s Electronic Advance Passenger Information System, and secured a smooth clearance through the U.S. Customs and Border Protection folks. A weather front had just cleared Bangor, so I delayed my departure to avoid catching up. I didn’t quite time it right, arriving at Moncton with 1000-foot ceilings and rain, forcing the first instrument approach of the trip. When nobody from customs came out to me, I secured my CANPASS clearance by phone. By then, the weather was starting to clear, so I departed to the north for a refuel and night stop at Sept-Îles, on the north bank of the St. Lawrence River.

Into Canada

Temperatures steadily dropped and the terrain became wild and unpopulated as I flew toward Schefferville in Northern Quebec during the next day. Passing Labrador City and the Wabush Airport brought signs of civilization. Another hour in the wilderness and some mine workings signaled the arrival at Schefferville. There, both local fuel suppliers indicated that avgas was unavailable, contrary to their entries in the Canada Flight Supplement. Enacting Plan B, a helpful local pilot ferried me to the gas station and I loaded 10 gallons of unleaded mogas into the plane to give a safe reserve for the next leg. As I was about to leave, I learned avgas was available, but only in 50-gallon drums.

The time came to don the immersion suit and lifejacket for the 100-mile leg crossing the Hudson Strait to Baffin Island in the territory of Nunavut. The strait was still 99% frozen, making a potential ditching an interesting proposition. Weather was generally good with the Iqaluit Airport reporting a broken cloud layer at 2500 feet agl and light snow. An easy visual descent across the solidly-frozen Frobisher Bay led to a comfortable landing at the Iqaluit Airport. Temperatures en route at 9500 feet had been around -18° C, which was beyond the capacity of the RV-8’s heating system, and made reaching the ground a welcomed event.

Fourteen days into the trip and this was the true Arctic—the start of the real adventure!

Across the Atlantic

I checked the onward weather the next morning to see forecasts of IFR conditions at my next planned stop and the alternates in western Greenland. The weather at Iqaluit, though, was cold and clear and provided a good excuse for a rest day to prepare for the next leg. Avgas at Iqaluit is sold by the 50-gallon drum. I bought the whole drum for $310 Canadian, filling all of the airplane’s tanks, plus two 5-gallon jugs to use for emergency fueling, and left about 10 gallons to support the local economy.

The RV attracted a fair bit of attention as I ventured north, and a chap came over to see me as I was going over the aircraft at Iqaluit. Wes Alldridge, the chief pilot of Air Nunavut, turned out to be enthusiastic about my trip and had lots of good advice based on his 30,000 hours flying in the Arctic. He affirmed that mid-Spring, before the sea warms with the threat of rapid fog formation, is a good time for clear weather. He also offered the use of their hangar to de-ice, if needed, before departure—something usually prohibitively expensive. Fortunately, I only had a dusting of dry snow and that assistance wasn’t needed. Wes also asked one of his King Air pilots to give me a guided tour of Iqaluit. Calvin Le Sueur is a keen young pilot, really interested in the RV and spending a few years in the Arctic developing his career skills. He loves the kind of flying they do.

The next day came with much better forecasts, so I filed for Ilulissat in Greenland, a place I was very keen to visit. Set in the beautiful Disko Bay next to the World Heritage Site, Ilulissat Icefjord, is a glacier above the fjord that moves over 60 feet a day and calves an incredible number of vast icebergs. Crystal-clear conditions greeted my arrival in Disko Bay after a 3-hour flight over a solidly-frozen Davis Strait. The Bay itself was open to the local fishing fleet and not icebound. However, the approach plates warn of possible icebergs as high as 750 feet msl on the approach!

My taxi driver from the airport sorted me with a private apartment at about a quarter the cost of a hotel—very welcomed with the high arctic prices for everything. I spent the remainder of the day exploring and enjoying the fabulous scenery. A walk around the town didn’t take long, seeing fields full of sled dogs basking in the sun despite the -12° C air temperature. A walk across the frozen inner harbor, followed by a hike on the trail to the nearby Ilulissat Icefjord, brought me to signs warning against going down to the beach due to potential tsunamis (commonly—and incorrectly—called tidal waves) caused by giant calving icebergs. It was a spectacular sight and a real highlight of the trip.

The next day, Thursday, seemed a good day to leave before the national holiday on Friday when the airport would be closed. I filed VFR at 11,500 feet over the icecap to Kulusuk, the only airport in eastern Greenland, which provided an opportunity to fly up the Icefjord, then climb above the largest ice field in the Northern Hemisphere. The largely featureless landscape and the veil of haze that often covers the area gave no distinct horizon, so the autopilot provided a great help. There are old Cold War early-warning stations on the icecap. While I fluttered with the idea of detouring to see DYE2, one of 58 Distant Early Warning Line radar stations, I held steady on my course east.

Eventually, the mountains of eastern Greenland came into view. METARs from Kulusuk were reporting a few clouds at 1500 feet and scattered clouds at 3000 feet, but there was a clear view of the sea and islands that allowed a VFR arrival. Despite light blowing snow at the airfield, arrival on their gravel strip proceeded uneventfully. I topped off with $18/gallon avgas, warmed up from the -18° C en route temperatures, checked the weather towards Iceland, and filed again for Reykjavik.

This leg stayed over the Atlantic Ocean for 380 n.m. and below cloud bases at 2,000–5,000 feet msl. With temperatures just below the freezing point, the cockpit once again felt toasty warm. Radio coverage was remarkably good, picking up Iceland radio about 100 miles out. Iceland controllers vectored me to the bay north of Keflavik, where I made a very pleasant approach to Reykjavik’s north/south runway. I had arrived in Europe, geographically at least. After the Arctic, it all seemed remarkably civilized and normal again. A big conference was going on in Reykjavik, and that meant the adjacent Hotel Loftleidir was full, so I found a place at the Radisson not far away. The taxi driver was also a Cessna 140 owner, making for a good chat over the short ride to the hotel. There was a fine, clear sunset over the Atlantic from my hotel room.

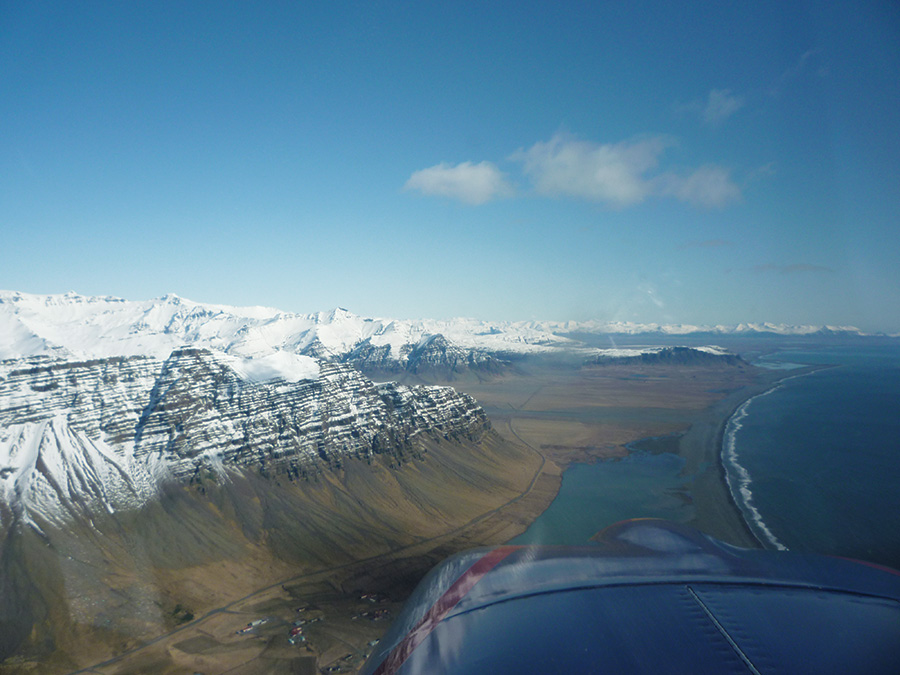

The next day dawned equally clear and fine. Scotland, however, was not so good, with cumulonimbus clouds (CBs), occasional heavy rain, and severe ice warnings at lower levels. I opted to enjoy a scenic tour around southern Iceland and reposition to Egilsstaðir in eastern Iceland. The move put me closer to Scotland and away from the worsening conditions approaching Reykjavik from the west. This proved to be a good choice, as the situation in the north of Scotland was steadily improving and Egilsstaðir remained in good, clear weather.

I filed IFR at 11,000 feet msl to Wick, Scotland, where I had arranged to do the paperwork for importing the RV to the UK. That route brought me above a scattered layer of cumulus clouds in excellent flying conditions. I flew past the Faroe Islands, a self-governing territory of the Kingdom of Denmark. Its single airport, Vágar, holds a notorious reputation for turbulence on the approach.

Arriving Home in the United Kingdom

Approaching Scotland, the remnants of the weather system could be seen with the tops of embedded CBs up to around my level, but easily avoided. Scottish information picked me up and handed me over to Wick approach at about 50 miles out, where I started my descent amongst the clouds and weather. Initially clear flying, I started to pick up very light icing at 5500 feet as I flew in and out of clouds. At 25 miles, I could descend to 2500 feet, which immediately melted the remaining ice. About 10 miles out, I emerged into the clear and could see the town of Wick and the airport beyond. Not wishing to make an unnecessary VOR approach, I cancelled IFR and landed at Wick with a 20-knot crosswind and rain, but glad to be on the ground with no more ocean to cross. The Far North Aviation crew marshalled me in and took me straight to the hotel, still wearing my immersion suit and life jacket. Paperwork could wait till tomorrow!

The next day, with paperwork sorted and weather improved, it was a pleasant 2.5-hour flight over now-familiar landscapes, stopping at Rolls-Royce Hucknall Aerodrome near Nottingham to see some old friends and then, finally, Enstone in Oxfordshire.

I’d arrived! It felt great…but it was now time to relax!

Editor’s Note:

Ironically, the journey never ends, and there is no rest for the weary. Just as Mark was leaving California for his trip home, he was offered a position with a new automotive venture in Silicon Valley. So, the RV-8 is now re-registered as G-RRVV and hangared at Enstone, England, while he once again lives 6000 miles away in California! He says he may be in the market for another RV-4 soon.