With 4000 kits sold, a million hours flown, and a loyal customer base, you just knew that the Kitfox would be back somehow find itself back in production. It’s been out after the previous company, SkyStar Aircraft, went bankrupt in 2005, leaving builders in the lurch. Now the Kitfox design gets to leverage its popularity—coming in part from its charming looks and in part from its well-developed airframe and complete kit—against the fulcrum of a new company headed by a management team that is experienced, well-liked in the Kitfox community and determined to avoid the mistakes of past administrations.

By the time you read this, Kitfox Aircraft LLC should be in its new facility in Homedale, Idaho, 20 driving miles from the old SkyStar headquarters in Caldwell. Flying, it’s 12.5 n.m. direct, but farther “as the Kitfox flies,” because it seems necessary to intercept the Snake River and then trace its meanderings downstream. Why? For fun!

Lexi, an Australian shepherd dog, greeted us at the door of the old facility, 25 miles west of Boise, with a wag of her stub tail. Some she doesn’t let in, and some she lets in the front door but not into the office of proprietors John and Debra McBean. The McBeans are the kind of people who belong in the aviation business, with avgas in their veins and oil in their joints. John’s father was a 30,000-hour pilot, and John started flying as a teenager. Debra is also a pilot, and both worked at SkyStar for five years before leaving to start a builder-assistance company that was intent on respecting the 51% rule.

Seven months ago, they and their partners bought the assets of SkyStar from the bankruptcy court, and are working to support existing builders and to get production restarted at an economically sustainable rate. The new facility has cheaper rent and lower taxes, cutting overhead by half. Moreover, the company starts with an unusual head start: It is debt free. “We’re in this for the long haul,” says John. The McBeans’ partners are three Arizona businessmen, all of whom are not just pilots, and not just Kitfox builders, but multi-Kitfox builders.

In the Beginning

Kitfox’s predecessor was the Avid Flyer, created by partners Dan Denney and Dean Wilson. (Incidentally, John’s dad was the test pilot on Avid serial number 2.) After a parting of the ways, Denney designed the Kitfox, similar to the Avid. The first Kitfox flew way back in 1984, if you can believe it, the Model 1 being a light, two-seat STOL airplane powered by a two-stroke engine. The Model 1 defined the Kitfox, with its vertical fin outline, the folding wing and the Junkers-style flaperons—combination ailerons and flaps mounted not in the wing trailing edge, but beneath it. The round cowl was for a Pong Dragon engine that never panned out, but the cowl shape remained for thousands more aircraft.

The Model 2 and 3 evolved with more powerful engines, increasing gross weights, and ever bigger vertical tails, but the new Kitfox Model 4 displayed more substantive change when it appeared in 1991. The flaperon linkage was changed for reduced adverse yaw, and the wing was changed from the original undercambered airfoil to a Riblett GA30U-612. There were actually two families of Model 4s, with gross weights of 1050 and 1200 pounds. The heavier version had a bigger vertical tail and a Rotax 912 engine. Two-stroke engines were still available on the Kitfox XL version, and the short-wing Speedster version was introduced.

The next big change was the 1994 Series 5 (no longer Model), originally designed for FAR Part 23 certification. Although a look-alike of the earlier aircraft, the Series 5 was in fact an entirely new design. It was marketed under the names Vixen and Voyager (with nosewheels) and Outback and Safari (with tailwheels). The maximum gross weight was up to 1400 pounds, later 1550, and Continental and Lycoming engines could be fitted. The distinctive round cowl gave way to a flat cowl.

On the Series 6 the original bungee gear was replaced with an aluminum spring landing gear that permitted field changes between taildragger and nosedragger, and the Series 7 had simplifications for easier construction.

What’ll It Be, Sport?

Today’s Super Sport is a further polishing of the design. The whole airplane has been scrutinized for extra weight and superfluous features, and some older “improvements” have been removed. The newest flaperons have an asymmetric airfoil, but the older style is still available with a slightly higher roll rate. Just so you can tell it from its brethren, the top of the Super Sport’s rudder has been squared off.

The Kitfox fuselage and steel pieces have long since been jig-welded, and the factory is full of fixtures. There are numerous small-diameter tubes, reminding me of the old Buecker Jungmeister biplane, which was carefully crafted for lightness. The wood parts, such as the floorboards, are amazing 10-ply Finnish plywood, 5-mm thick and CNC cut. No more of this tracing and cutting stuff that the real men had to do when they weren’t out walking to school at 40 below, uphill both ways.

The tail feathers are steel weldments, given airfoil shapes with “intercostal” (meaning between the ribs) plywood pieces that are bonded to the steel frames. The more aerodynamic tail surfaces give better control authority, probably less drag and certainly better looks. The intercostals, which show attention to detail with plenty of lightening holes, are optional on the vertical fin and rudder.

John pays great attention to weight. Showing me the next Super Sport under construction, he pointed out different features and how much weight they save. For example, the old dorsal fin has been replaced with a simpler design that saves just over a pound and a half.

Thanks in part to this focus on weight savings, the Super Sport is a true hauler with the optional landing gear upgrade, boasting a maximum gross weight of 1550 pounds. Built light, the expected empty weight with the Rotax 912S is 750 pounds. In other words, the useful load is more than the empty weight! The plane has been tested at 1550 pounds to ultimate loads of nearly +6/-3 G, giving the FAR 23 limit loads of +3.8/-1.5 G.

The company demo plane had the tricycle gear with a bunch of options and weighed 801 empty, but a customer airplane (taildragger) in the hangar weighed in at 756. With the stock landing gear, max gross weight is 1320 pounds, the magic number for Sport Pilots. The lighter Kitfox could carry 28 gallons of fuel and two ASTM-standard 190 pound occupants with 16 pounds left over.

In the Air

Early winter storms were teasing Caldwell, and the surrounding mountains, bathed in fresh snow, glistened pristinely. A break in the weather let us sneak into the air for an evaluation flight, sparing us the ordeal of just-above-freezing temperatures that photographer Richard VanderMeulen had to endure on his earlier visit. Not to worry about the temperatures, though. N102YB, the McBeans’ personal aircraft and the company demonstrator, had an effective heater. The 100-horsepower Rotax 912S up front provides hot water to a radiator core in the cockpit, and a pair of DC fans controlled by a tiny knob on the instrument panel circulate the warmth. Some builders put a shutoff valve in line with the heater, and the Arizona builders usually omit the heater altogether.

Boarding was not hard. With the top-hinged door open, back into the seat with both legs dangling outside. Pull the stick all the way back and swing yourself in, with the inside leg going over the stick. Shoulder room is advertised as 43 inches, and John and I never touched.

A side benefit of this steel-tube cage’s design—aside from strength (the company claims that no Kitfox has ever had an in-flight airframe failure)—is that there are no tubes directly overhead to crease your noggin in turbulence, and headroom is outstanding. With tricycle gear and optional bowed-out acrylic doors, visibility was excellent.

Like most tricycle-gear homebuilts, steering is with differential braking. With just a little bit of taxi speed, the rudder becomes effective, and brakes aren’t needed. The seating position is fixed, but optional adjustable rudder pedals put them where you want them. If your passenger doesn’t want to fly, you can put the pedals full forward.

John let me try the first takeoff, and I got a surprise. The elevator trim was set to nose up, and when he told me to rotate, I applied more stick pressure than was required. We popped off the ground, but John’s quick push forward on the stick saved us any serious embarrassment. Part of the problem was too much stick-back trim, as this airplane did not have the trim-position indicator that is standard on the current kits. Appreciating this, I was able to make my later takeoffs much better.

Climbing at 70 mph indicated in the cool air, we showed an easy 500 fpm passing through 3000 feet msl. Later in the climb, at 80 mph, we still showed 500 fpm. First on the agenda was a speed run at 5000 feet msl, with an outside air temperature estimated at 20° F. Our two-way average with 5300 rpm on the tach was 99.5 knots, according to the GPS, in line with the advertised 105-knot cruise speed that was no doubt found at optimal cruise altitude.

A quirk of this particular airplane was that one wing was heavy, a condition that became noticeable to the McBeans on their way home from Oshkosh. While not that big a deal, it hindered good rudder coordination and an unfettered evaluation of control harmony.

A Minor Mystery

During power-off stalls, the Kitfox didn’t really break, so I started playing around, trying to keep the wings level with just the ailerons. That worked for a while, but eventually adverse aileron yaw won. If you’re determined to ignore the obvious warnings of aerodynamic stall, you’d best use the rudder.

We practiced maneuvers with full flaps. As expected, the roll rate decreases with full flaps, but not as much as on the earlier models. However, when you apply some aileron deflection, there is a tendency for the ailerons to deflect further. This is disconcerting, but not a problem in maintaining control.

Like other high-wing airplanes with generous flap area, the Kitfox requires that you keep up with the elevator trim. As installed, the relatively fast electric trim is just what you want for go-arounds when you need a lot of change, quickly. For cruise flight, however, you’d want to install a two-speed trim for better control of fine changes—or you’d need to get used to “blipping” the trim.

With power on, the Kitfox hung on its prop for a long time before starting to announce an impending stall with a shudder and then, with the ball centered, lowering the nose gracefully straight ahead. There was no abrupt break, but neither was there the hard, fast shaking often encountered in planes with stall strips.

The warnings of impending stall are there and clear to those who are not distracted. But given that many Kitfox accidents have happened during “maneuvering flight,” often a euphemism for flight at low altitude with attention outside the airplane, it would make sense to install a stall-warning system, and those are available. Various models of the Kitfox have been spun, but no formal spin test program has been performed.

The airspeed was a mystery in these stalls, however. In maneuvering before the power-on stall, the airspeed suddenly jumped from 43 to zero. While it’s not necessarily unheard of to see zero airspeeds, that much jump, abruptly, was unusual. When doing the power-off stalls, holding the stick back, the Kitfox airspeed vacillated between 40 and 70 mph, while the feel of the airplane was of being continuously in the stall. Those speeds were observed in flight, but afterwards, did they make sense?

The pitot tube is ahead of and below the wing, seemingly in clear air, so that didn’t offer an explanation. And during slips to landing, the airspeed also seemed high. High airspeeds are often encountered in slips, but these came without the attitude and audible cues you might expect.

Watching the Detectives

Specifications are manufacturer’s estimates and are based on the configuration of the demonstrator aircraft. As they say, your mileage may vary.

That night over burgers, we discussed the airspeeds. I’d never seen variations of such magnitude at low airspeeds, and they didn’t seem to make sense. But there they were. Finally, I asked John where the static port was, and he said that it was 2 feet ahead of the elevator and 2 inches below. During testing that could have been used for certification, that location was found to give accurate readings when compared to a flight test boom sensor.

Only one aft fuselage static port? Yes. But then, that single static port location was on many Kitfoxes. This made me think back to other airplanes I’d flown with square tailcones, such as the Avid Magnum, Wittman Tailwind and Sorrell Hyperbipe. All of those showed less than wonderful yaw stability, perhaps because the square corners of the fuselage could easily generate vortices. The Kitfox has enough vertical fin to avoid the yaw instabilities of the square fuselage, but might there be fuselage corner vortices playing practical jokes on the one static port? I suggested installing dual ports and checking, but John had a better idea: disconnect the static line inside the cockpit and see what happened during slow flight. The airspeeds would not necessarily read correctly, but that wasn’t the point.

The next morning, with temperatures in the teens and a whopping 30.58 altimeter setting, we launched to try it out. Sure enough, the airspeeds during stalls and slow-speed turns were solid, with none of the exaggerated excursions we’d seen the day before. Maybe it was fuselage vortices, or maybe it was just faults in the static system. Furthermore, with the washout of the wing adjusted, two-thirds of the wing heaviness had gone away and rudder coordination was much easier.

Back to Earth

Patterns in the Kitfox are flown at 70 mph, maybe slower on final. Even with full flaps, the approach is not nearly as steep as a Cessna with flaps at 40. That approach is clearly on the back side of the power curve, but it’s easily controlled with the throttle. I asked John to demonstrate the first landing, and our landing roll took us just past the runway numbers, even without abusing the brakes.

My landings weren’t as practiced, but I had little trouble landing pretty much where I wanted, on the centerline and with a nice flare and touchdown. On one landing, I tried full flaps, and found that aileron phenomenon tolerable with my experience level in the airplane, in calm air.

On the second flight, just for fun, I flew the approach fast with no flaps to see what it was like. John said we would float, and we did, but not as much as in my Cessna 175. Plus, the float was much more controlled and easier than trying to hold altitude in the Cessna. Maybe the push-pull controls get the credit. This kind of approach would feel more comfortable to many pilots, but the prolonged flare would require more attention and skill to stay on the centerline in a crosswind.

One mannerism of the Kitfox tricycle gear appeared on takeoffs and landings. As mentioned, the nose seems to pop up some after takeoff, but on landing, the nosewheel tends to drop to the runway seemingly of its own accord unless additional back pressure is added after the mains touch. Maybe the main landing gear is just a touch too far back. It’s not a problem on landing, but it can surprise you on your first takeoff, or on a go-around with full flaps and the trim set for the approach.

Up and at ‘Em!

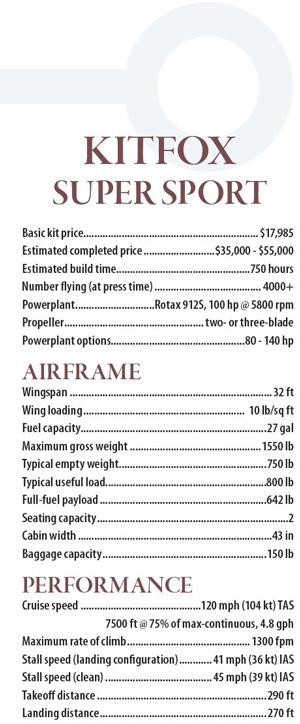

More changes are in the works. John is looking at carbon fiber for the rudder leading edge and vertical fin trailing edge. Cost will decide whether that idea sees production or not. He’s also planning to try full-span, carbon-fiber leading-edge cuffs. For the moment, the company is pricing the basic kit at $17,985—and predicting a completed cost between $35,000 and $55,000, depending upon how lavishly equipped you want it to be—and turning its attention to being profitable at that figure. That there are more than 4000 Kitfoxes flying, according to the company, will bolster sales of parts and further support the new firm.

After the second flight, John invited me to sit in a Kitfox Model 4 in the hangar, just for comparison. The difference was striking. The Model 4 is obviously narrower in the fuselage, and would be tight with two people. While purists may lament the increased size of the Kitfox Super Sport, there’s no denying the increase in utility. The Kitfox is a real airplane now, no excuses required.

The new Kitfox is about generous payloads and easy short takeoffs and landings. John says it’s “a light, back-country fun airplane. It will do everything a Super Cub will do, and at 5 gallons per hour. And faster.” Even if you’re not going into the back country, the newest incarnation of the Kitfox is still a winner. Great to have it back among the living.

For more information on the Kitfox Super Sport, call 208-337-5111 or visit www.kitfox.com.

Goodmorning

I would like to know the price of the basic construction kit without engine and if it is possible to adapt other types of engine and if yes possibly the minimum and maximum power!

Regards

Edoardo