If I had to choose one thing that would do the most to grow the sport of powered parachuting, weight-shift control trikes, and, frankly, all of sport aviation, it would be the ability to do commercial work. Sport aircraft have unique capabilities and built-in economies that make them ideal for aerial photography, farm management and touring flights—work that may otherwise be accomplished in a million-dollar helicopter.

Unfortunately, the FAA doesn’t allow a path for pilots to become commercially rated in powered parachutes or weight-shift control trikes. The “glass ceiling” for those categories of aircraft is Private Pilot level, which offers few additional privileges beyond Sport Pilot. The only commercial work you can do as a Private Pilot is demonstrate an aircraft in flight if you are an aircraft salesperson, and tow gliders and hang gliders. That is in addition to being able to earn money as an FAA-certified flight instructor (CFI) providing flight training, which you can also do with a Sport Pilot rating.

What Is Commercial?

Commercial aviation is an unusual term in the aviation regulatory world. A strict black-and-white interpretation of “commercial” by the FAA would shut down a large part of the civilian flying economy.

For example, flight instruction—though rarely free—is not strictly considered a commercial activity. That is reflected in a couple of ways in the regulations as well as in other official documents—not the least of which are the privileges listed in the FAA regulations for Sport Pilot instructors. But interestingly enough, a Sport Pilot CFI is specifically authorized only to “provide training and logbook endorsements for” all kinds of training activities. However, the FAA doesn’t define the word “provide,” and if you check the dictionary, the definition implies a one-way transaction. That is, while a CFI can offer or supply flight instruction and endorsements, there’s nothing in the regulation about taking money for it. But that certainly is the way it’s done, despite the rigid definition of “commercial operator” as defined in Part 1 of the FARs.

Generally, pilots who want to do commercial operations get a Commercial Pilot rating. That rating allows the holder to act as pilot in command of an aircraft:

(i) Carrying persons or property for compensation or hire, provided the person is qualified in accordance with this part and with the applicable parts of this chapter that apply to the operation; and

(ii) For compensation or hire, provided the person is qualified in accordance with this part and with the applicable parts of this chapter that apply to the operation.

And this is important: Airship or hot air balloon Commercial Pilots can also act as flight instructors for their category and class of aircraft. (That may offer a creative way to solve the issue for powered parachutes and weight-shift control trikes!)

For adventure seekers, the open-cockpit feel of weight-shift control trikes may be the perfect introduction to flight.

The Commercial Pilot rating exists as a stepping-stone from a Private Pilot rating up to an Air Transport Pilot rating. It is also a prerequisite to becoming a general aviation (FAR Part 61, Subpart H) flight instructor. The rating allows airplane, rotorcraft and even hot air balloon pilots to fly some pretty heavy aircraft with more than one or two people on board. (Yes, I know. How can you be heavy and lighter than air at the same time?) But it’s also a required rating for banner towing and all of the other commercial work we would like to see for powered parachutes and weight-shift control craft.

Who Wants the Rating?

The good news right now is that nearly all of the parties the government calls “stakeholders” are interested in having a commercial rating for powered parachutes and weight-shift control trikes. Manufacturers, of course, would like to see new markets opened up for their products; pilots envision business opportunities for flying their aircraft; and even the FAA finally recognizes that commercial privileges for pilots would help it out.

It wasn’t always that way. While the community long saw the benefit of a commercial rating for powered parachutes and weight-shift control trikes, as recently as a decade ago, the FAA did not. The mindset may have been along the lines of limiting the regulatory changes to a package that would be a drop-in replacement for the old two-seat exemptions that were used for training. Within that scope, the Private Pilot rating for the two categories made sense because there were tasks such as flight testing, aircraft sales and glider towing that needed a higher rating than Sport Pilot, but fell short of a commercial rating. And flight instruction was dealt with cleanly in its own chapter in Part 61. Or perhaps the FAA wanted to get part of the package wrapped up before even more changes were explored.

In any case, two high-profile occurrences in the trike world have pushed commercial ratings a little closer to the regulatory front burner. The first was bad news for the FAA, and the second was even more bad news for the FAA.

The first issue was the trike fatalities that plagued operations in Hawaii last year. The operations were legal—the pilots were all at least Sport Pilot CFIs, and the aircraft were Special Light Sport Aircraft (SLSA). But a varying mix of challenging conditions, poor aeronautical decision-making and less-than-optimum maintenance on the part of some instructors resulted in instructors and students paying the ultimate price. The fact that this happened more than once attracted attention from people in Washington, D.C. One of their first questions was: “What is going on here?” The second question was: “Aren’t these commercial operations and not training operations?”

The answer to the first question is complicated, and the answer to the second question is nuanced. The trike operations really were training operations in the legal sense of the term. The aircraft were legal, and the instructors were legal. Most likely, not all of the clientele intended to take more than a first lesson—at least not in Hawaii. But many such students do follow up with lessons when they get home from vacation. This is not much different from normal CFI operations. After all, who knows who will end up continuing with lessons and who won’t? In fact, one of the big problems with general aviation flight training is the dropout rate. But the basic issue remains: There is no path for the pilots to get a commercial rating.

For agricultural crop scouting, aerial photography, pipeline surveillance and several other low-and-slow flying tasks, the inexpensive and easy-to-learn powered parachute is hard to beat.

The second issue came up last Christmas when Operation Migration temporarily halted its trike trek south, leading endangered whooping cranes to their winter digs. The question had already come up a few times from another trike pilot who also wanted to fly commercially. His question was along the lines of, “How can I get paid to fly like the Operation Migration pilots?” It turns out that the Operation Migration people had previously—and successfully—argued that because the pilots were paid to take care of the birds, using their trikes to lead the birds south was simply “incidental” to their employment.

The FAA realized that good deeds were being done and relaxed the litmus test of commercial operation for Operation Migration the first time the question arose. However, the second time the question came up, the FAA decided it was time to investigate. The Operation Migration folks responded by shutting down operations mid-migration. That got into the news and caused a big stink. The FAA worked things out by providing a temporary exemption to the rules just for Operation Migration with the promise that a longer-term solution would be in the works.

The hope is that any longer-term solution will address the entire trike community and not just the Operation Migration pilots. But I would suspect the FAA really doesn’t want to get into the exemption business if it can be avoided, and in this case it can be.

Potential Paths to Commercial

If there is some motivation for commercial licenses, how do we get there? Fortunately, there are two paths we can follow: Extrapolate from airplane ratings and extrapolate from lighter-than-air ratings.

A standalone commercial license certainly seems the natural way to go for those pilots who grew up in the airplane world. It’s a normal part of the hierarchy that begins at Student Pilot and ends at Airline Transport Pilot. The Commercial Pilot rating is a waypoint on the path to the Airline Transport Pilot rating that still allows an airplane or helicopter pilot to fly some pretty impressive aircraft (up to just over 6 tons maximum takeoff weight) and carry lots of people and cargo. That’s because in FAA terminology, aircraft weighing less than 12,500 pounds MTOW are still considered small and can be flown by a Commercial Pilot if they aren’t turbojets.

When you contrast those Commercial Pilot privileges with a powered parachute or weight-shift control trike that is capable of flying one, two or possibly three people, it seems like the rating—and the requirement for a second-class medical—is overkill.

The other side of the coin is the Lighter-than-Air Commercial Pilot rating. That rating doesn’t require a medical. Moreover, once you get a commercial rating in this category, you are also allowed to provide instruction in this category. Although this allowance is unique to this aircraft category, it doesn’t have to be. It is appropriate to point out the commercial ratings for lighter than air (and the accompanying instructor rating) predate the Sport Pilot rules by decades, and they seem to have worked out well.

The same general idea can be used in powered parachutes and weight-shift control trikes, but rather than adding instructor privileges to a commercial rating, why not add commercial privileges to the instructor rating?

There are several reasons this strategy could work. First, the requirements for an instructor rating for both powered parachutes and trikes are really about where the requirements for a commercial rating for those categories would end up.

Another good reason is that the most demanding task for a trike or powered-parachute pilot is flight instruction, and the instructor certificate already covers this. Less risky tasks such as crop observation, aerial advertising, aerial photography, pipeline observation and leading migratory birds on their winter break are a walk in the park compared to teaching others how to fly. Why not just change this one part of the regulation?

The last area of concern might be passengers. However, passengers are already being carried during Sport Pilot flight instruction, as well as with medical-free pilots in the lighter-than-air and glider categories. When you combine that with the practical limits of how many people a powered parachute or trike can carry, there doesn’t seem to be a need for a whole new rating beyond the flight instructor certificate.

Whatever path the FAA takes regarding commercial privileges, I hope it will not attach a requirement for a second class medical. The performance window of powered parachutes particularly, and to some extent trikes, is closer to gliders or lighter-than-air, so it would make more sense to have similar medical requirements. An exception may be for night flight, in which case a third class medical may be appropriate.

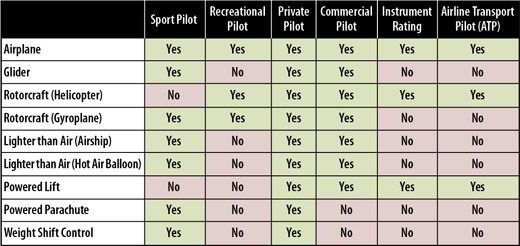

Ratings and privileges available to the different categories and classes of aircraft.

What to Fly

The good news is that there are a lot of powered parachute and trike designs already on the market that are fully capable of performing commercial operations. The bad news is that you can’t do commercial work with SLSA other than glider towing and flight instruction (even though flight instruction isn’t strictly commercial work).

There are two possible solutions to this issue. The first is to force manufacturers to produce standard or primary category powered parachutes and trikes or to update §91.326 allowing SLSA powered parachutes and trikes to do commercial work. This SLSA trike and powered parachute equipment has a good safety record, so it seems like a reasonable approach.

Motivating Pilots

Unfortunately, the Sport Pilot rules have not had the positive impact on the safety and popularity of powered parachutes and trikes that was expected. Instead, the added burdens of certifying pilots and aircraft have adversely affected the sport. The opportunity to do work commercially may help to reverse that trend and increase the popularity of low-cost flying by exposing more people to these aircraft and motivating them to get involved with low-and-slow flight.

![]()

Roy Beisswenger is the technical editor for Powered Sport Flying magazine (www.psfmagazine.com) and host of the Powered Sport Flying Radio Show (www.psfradio.com). He is also a Light Sport repairman and gold seal flight instructor for Light Sport Aircraft as well as the United States delegate to CIMA, the committee of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) pertaining to microlight activity around the world.