As the Experimental/Amateur-Built sector continues to mature and evolve, more homebuilts are sold into the used aircraft market. That makes sense. In the early days, building on your own was a way to afford a particular kind of aircraft, trading your labor into the cost of acquisition. But more recently, homebuilt aircraft are desirable for many more reasons, including the availability of stunning technology-both in avionics and ahead of the firewall-that is either far too expensive in series-built aircraft or not available at all. There is also an economic incentive: Building remains less costly than buying a certified aircraft, even with a generous age margin built in. Isn’t a 15-year-old Van’s RV-6 more exciting than a 30-year-old Cessna for the same money?

With more than 30,000 aircraft registered as Experimental/Amateur-Built-and more coming online every year as Experimental Light Sport Aircraft-there are choices aplenty. But the mindset for the buyer looking at a completed homebuilt has to be different than for someone looking to build, either from a kit or from scratch. When you’re building, you are wedded to the kit manufacturer or the supporter of the plans, be that the original designer or, as is increasingly common, someone down the line.

When you buy a finished kitbuilt, you are now joining hands (metaphorically speaking) with both the kit maker and the builder. The questions multiply. Is the kit a good one, with strong support and a vibrant user base? And did the guy who took those parts home and participated in that active group actually do a good job of building an airplane? To some extent, these issues are interrelated, but it’s also possible to build a stunningly good airplane from marginal plans as well as a clunker from a mature, thoroughly developed crate of kit parts.

Education is everything. If you’re considering buying a fabric airplane, by all means attend a workshop to learn more about the process. You’ll end up knowing what to look for in a used aircraft.

Knowledge Is King

As you start the search process, your first job is to identify your mission. Long-distance travel for pleasure? Forget the Cub-like aircraft; the country seems pretty large at 100 mph. How many seats? Many builders with four-seat (or more) aircraft find that their average load is something like 1.9996 passengers (allowing for rounding error). In this case, building a less expensive, more efficient two-place and renting something with four seats when needed is clearly the way to go. (Ego aside, naturally.) Shopping doesn’t start with a particular airplane in Trade-A-Plane or on Barnstormers.com, but in identifying the need.

As you start to define the need, identify the manufacturers filling it. While you can have a happy relationship with a previously built Experimental from a defunct company, your life will be much easier if you choose a design with some factory support. You might not need a lot, but it’s far better to have it available. Also, remember that the factories aren’t obliged to provide live tech support for a secondary buyer-after all, you didn’t pay them a dime for the kit.

Technical advice is available from other sources, and the Internet has provided ample opportunities for eduction. Google-search your way around; try something like "Van’s RV Forum" or "Glasair Builder’s Group" in the search engine. Check the kit manufacturer web sites as well, because many of the good ones recognize the value of peer support and have embraced these independent groups.

Find a Mentor

Becoming an active watcher of these virtual clubhouses will help you find an individual or group of builders to take you to the next step, which is an intelligent, deliberate, informed inspection. This idea bears strengthening: Never purchase an airplane you haven’t inspected and flown. Actually, that’s have it inspected and have flown by someone who knows what he is looking for in terms of construction and flying qualities. Lack of familiarity with a design can disguise symptoms of troubles beneath the surface: a heavy wing, poor rigging, sub-par performance, a heart-in-throat wing drop at the stall. All of these could indicate poor build quality, but they could also be remedied by small adjustments. Bringing someone with intimate experience in the type will help you sift these impressions.

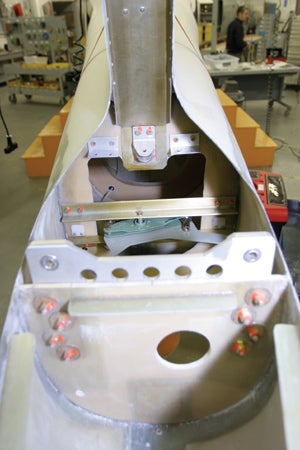

The quality of the firewall-forward construction is crucially important, as is determining the pedigree of the engine and its accessories.

It is reasonable to help defray travel costs for this mentor, and you should be willing to pay for meals and such as a gesture of thanks. But also remember that unless you’re contracting with a recognized business, this mentor’s efforts should be considered advisory only, and it remains up to you to make the final decision. For that matter, be cautious if a third party begins pushing hard for you to purchase a specific airplane. Likewise, be sure to dig down to the real reasons your mentor wants to reject a particular airplane. The answer, "I don’t like XXX engines" isn’t good enough with simply a gut feeling and thin anecdotal evidence. Again, go back to the firsthand experiences of the local builders’ group for sound guidance.

Even better if your mentor is an Airframe & Powerplant mechanic, which brings up one of the only downsides of owning a homebuilt constructed by someone else-the annual condition-inspection sign-off. As you probably know, first builders can obtain a Repairman Certificate for the airplane, giving them legal authority to perform all maintenance and sign off the annual inspection. Technically, anyone can work on an Experimental/Amateur-Built aircraft and make minor modifications, but the annual inspection must be signed off by the holder of the Repairman Certificate or an A&P mechanic. (An Inspection Authorization is not required.) One of your first tasks is to locate a willing A&P to assist you with ongoing maintenance and the sign-off. Some A&Ps are unwilling to have their signatures in homebuilt-aircraft logbooks, but there are plenty who will assist you.

Logbooks and Records

No airplane should be considered unless the complete logbooks and builder’s manuals are available. There are exceptions, of course, but without documentation, every single piece of the airplane that you can’t see or touch is now in question. What is the pedigree of this engine? How many hours on the prop? Have the mags been rebuilt or overhauled? Is the pitot-static inspection current? If the logbook entries are unclear or missing, then you need to think twice about that particular airplane or start working on financial offsets to protect yourself.

Photographs of the build help make a used Experimental more desirable. Even better is access to those parts of the structure for an inspection.

Look for compliance with Service Bulletins-from the kit manufacturer but also from the engine, propeller and accessory maker-and Airworthiness Directives. It’s true that once past the initial airworthiness inspection a homebuilt is not bound by AD notes, but careful builders will keep track of and generally follow them if safety of flight is an issue. A response from the seller of, "Oh, ADs don’t apply. I just ignore them," could indicate a certain carelessness with the overall maintenance of the airplane.

When you corroborate the logbooks with an inspection of the actual airplane, pay most attention to the firewall forward, because the engine is the single most expensive part of the airplane and represents the greatest financial risk. Ask these questions: Who built the engine? When? To what specification? How is it different from a standard engine of the same type? What accessories have been added? Is it a new engine, a first-run overhaul, an engine taken from a damaged certified airplane, or one made from components from several different engines? An engine directly from the factory or from a reputable engine builder is the ideal choice, though a well-documented field overhaul is a fine option if it was built correctly.

While you’re poking around beneath the cowling, look for nonstandard hardware, proper use of safety wire, the quality of the baffling, cleanliness and general workmanship. Again, your mentor can help you identify where the airplane you’re considering commonly diverges from standard aircraft practice, and where it should not.

Total Time, Hours and Years

Be wary of purchasing an airplane that is just out of Phase I flight test. While it is true that some builders enjoy the act of assembly more so than the flying-or perhaps they have lost their medical-it is also possible that the builder either scared himself in the airplane, or found something really wrong that would be too expensive or dispiriting to remedy. Probably the ideal number of hours is in the 200 to 500 range, though there is absolutely nothing wrong with considering a 1000- or 2000-hour airplane that has been well maintained. In fact, when you look at calendar versus Hobbs time, consider that an airplane flown regularly, every year for, say, 50 to 100 hours is much better than one that flew 200 hours in its first year and only five every year after that. Sitting is far harder on an airplane, the engine especially, than flying.

Metal structures allow for simpler inspections, but that doesn’t mean problems can’t hide. The more quickbuild components the better to ensure consistent quality.

Metal Versus Composite

There are arguments on both sides as to which material represents the least risk, but it should be noted that inspecting an aluminum airframe is considerably easier. All of the major structures should be open to viewing, and construction mistakes will be evident. This is not to say the structure can’t hide surprises, but a metal airplane will typically disclose its condition more readily. Once more, make use of your maintenance mentor to help you find the common wear points for the airplane you’re considering. Every airframe has areas of weakness: skins that crack, rivets that are prone to loosening, parts that break in and wear on one another.

Composite airplanes tend to have simpler structures overall (fewer, bigger pieces that make up the whole), and poor construction methods can be hidden by a shiny coat of paint. Here you absolutely must consult with a fiberglass expert. There are ways to non-destructively inspect composite structures for proper construction and for damage. Typically, you will be able to see a number of layups inside the airplane-in the tail cone, for example-that might give you an idea of the overall workmanship. Composite layups should be neat and appear fully wetted, but you should not see drips or other evidence of excessive resin/epoxy use.

Because most modern designs are available as quickbuild and "slow build" kits, the safest route is to choose an airplane made up of as many quickbuild components as possible. Generally, the people who make these QB parts are professionals, and while they’re not perfect, the error rate is generally lower than it is for amateur-built pieces. A factory-built wingspar, for example, would have to rate as a positive, as would participation in a builder-assist program. Overall, airplanes built with proper supervision are of better quality, and the number of newbie mistakes are minimized if not entirely eliminated.

The Shiny-Shiny

As buyers, it’s easy to be distracted by a panel stuffed full of the latest avionics or a paint job to die for. But the paint is probably the least important piece of the puzzle here, as it does nothing to make the airplane airworthy. Instead, concentrate on the quality of the avionics installation, not the specific boxes, and look for full documentation. If the panel has an IFR GPS, the airplane will have to have undergone a flight test as part of system validation to be truly legal; see that this is documented in the logs.

During your flight check, exercise every piece of equipment, all the lights, everything. Now is the time to discover that the GPS wasn’t hooked to the autopilot for nav tracking, or that the nav lights pop the circuit breaker.

Take Your Time

The final bit of advice concerns deliberation. Quick decisions are more often bad decisions than they are a stroke of genius. Spend some time with the seller, and try to understand the motivation behind his decision to sell. It’s difficult to part with an airplane you have spent years building, so you should understand what brought this about. There may also be clues about the airplane’s condition in this explanation.

Great airplanes and good deals are out there. But as with any open market-whether it is certified aircraft, cars, boats or motorcycles-there are bound to be clunkers, too. Make friends in the community who can help you look for the diamond and make it your own. Oh, and welcome to the club.