In Genesis Chapter 1…the part that was edited out…the essence of gorilla went before the Lord and said, “I want hair.” The Lord said, “It’s gonna cost you brains.”

That parable has carried aviation meaning to me for over 30 years since the first time I heard Gallagher deliver it. It means that you can ask for anything you want in life, but nothing comes free: There is always some cost.

And so it goes with aviation. You can just pick up the gun and start pounding rivets, but at some point you really ought to examine the plans first. Yes, you can jump into your Little Toot, kick out the chocks, and just blast off…but shouldn’t you get a weather check first? Instead of hugging that interstate all the way to Albuquerque, I see you plan to skirt west into a headwind to avoid that line of weather. Did you recheck your fuel requirements?

Aviation’s Blueprint

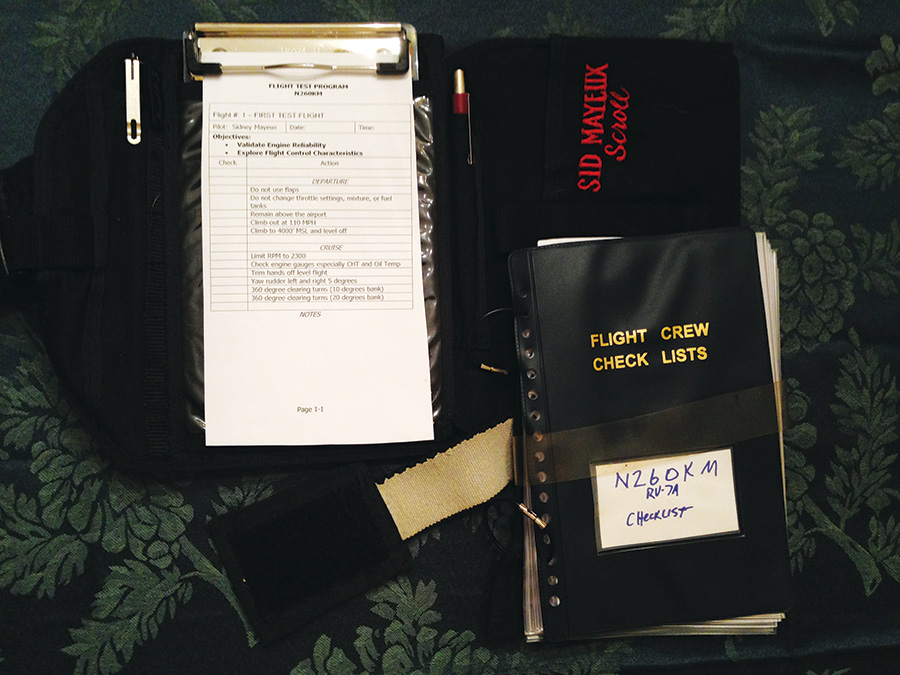

In 2010 I received my RV-7A empennage kit and build manual, and had already constructed my workshop in the basement of my officers’ quarters at Langley Air Force Base, Virginia. I paged through the big white plans drawings and leafed through the manual. I was excited…and completely lost. Where do I begin?

My friend and fellow builder, Kent Stitt, rescued me. He dropped by and gave me a “progressive taxi” through the way he tackled each phase of construction. “First, start at the beginning of the empennage section in the manual. Read every word,” he said, tapping the pages. “Then read it again, but this time follow along item-by-item in the plans drawings. You can fit the parts up against each other like they look in the drawings. It’ll start to make sense. Pay attention to the types of rivets, direction of dimple, and such. When you’re comfortable with that mental picture, then start drilling.”

It helped that Kent and I both flew in the Air Force. Even though we flew different fighters, we both grew up in an aviation world that demanded extensive planning before every mission. Rather than calling it “flight planning,” we called it “mission planning,” and I still keep the “mission” mindset today.

Every flight, every hole drill, every fiberglass layup, every takeoff and landing starts with a plan. It’s the blueprint for what we expect to accomplish during today’s mission, given today’s conditions and resources, and how we intend to handle things when they don’t go as planned. Some events require less planning than others, but all require a plan if we want any hope of a safe and successful outcome.

I see four pitfalls that can smack us when it comes to planning, and we have control over three of them. We can conduct cursory, but incomplete, planning. Conversely, we can conduct extensive planning, but not catch and eliminate errors in our planning factors. Of course, we can chose to not plan at all, trusting instead in our skills (or luck?). However, we can’t do much to avoid the fourth pitfall involving information, or the lack of it: We can plan our butts off, but if we don’t have all the facts, we’re in trouble.

KC-135 tanker crews from McConnell Air Force Base plan an aerial refueling mission in support of B-2 Spirit bombers from Whiteman Air Force Base. (Photo: U.S. Air Force Photo/Airman 1st Class John Linzmeier)

Inadequate and Erroneous Planning

In 2006, a VFR RV-8A pilot was approaching a weathered-in airport for landing and radioed his intention to circle the airport until the fog lifted. Minutes later, the aircraft descended into trees and impacted a frozen pond only a half mile from the runway. Observers said the pilot had departed an airport with one-half-mile visibility from fog, and the observed vis at the destination was 400 feet with, at best, a 100-foot ceiling. Investigators could not find any record of the pilot receiving a preflight weather briefing. The NTSB said the pilot failed to obtain a preflight weather briefing for his destination airport and initiated flight into known adverse weather conditions.

A similar event took the life of an airline transport pilot flying a VFR cross-country in a vintage F6F Hellcat in near-IFR conditions without a weather briefing or a filed flight plan. This time, 500-foot ceilings and fog obscured the peaks of the Cumberland Mountains and forced the pilot down to 100 feet agl as he paralleled an interstate highway. He could not avoid the power lines that crossed the gap over the highway in his flight path: The wire wrapped around his prop and crankshaft, and he lost control and crashed. The NTSB investigator identified the pilot’s inadequate preflight planning and incomplete evaluation of the weather as the accident’s probable causes.

Despite decades of these risk management lessons, pilots continue to die from their own failure to plan the flight. Even on a simple day-VFR cloud hop, it makes good sense to check the weather and NOTAMs for any gotchas waiting to upset the plan. But once we’ve built the plan, we’ve got to check the plan for errors. Quality control is one of the most vital parts of mission planning.

Has an approaching cold front ever caught you by surprise? Even a short VFR hop requires mission planning, and must include a check of the weather and NOTAMs. (Photo: Paul Dye)

A two-ship of F-15E Strike Eagles had finished their station time supporting ground troops on a night close air support mission in Afghanistan. On RTB, they had enough fuel to fly to a safe area and practice simulated NVG high-angle strafe against a known training target. This crew had flown this event before. However, on this night, when they planned their simulated attacks, they made a fatal math error, and nobody in the flight caught the error. With the actual target elevation 5000 feet higher than their calculated target elevation, they rolled in and dove straight into the ground. The Accident Investigation Board cited as causal the accident crew’s incorrect assessment of the target elevation, as well as the crew’s blind reliance on the incorrect number.

I see similar math error landmines in Experimental and general aviation. From time-distance-speed calculations to fuel predictions, wire runs, and gauge/amperage requirements, these mission plans require calculations that, if wrong, can spell trouble on the ground and in flight. I do my math, then set it aside and come back later to check it. If I’m not sure, I hand it over to a pro who has dealt with these figures before. Don’t trust your math until you have verified it.

I’m 100% Positive I Don’t Know It All 100%

We aviators have a sort of “right” to expect accurate and complete information regarding weather, airfield status, construction plans and instructions, and such. On that rare occasion when we discover holes in the information, we have ways to report the problem and get it fixed. If the error is in the aircraft construction plans, we can call the manufacturer and notify them. We can also log onto online communities and get the word out. For example, the Van’s Air Force web site has quite a few postings from RV builders who came across errors or omissions in their planes’ plans.

NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (http://asrs.arc.nasa.gov) captures confidential reports, analyzes the resulting aviation safety data, and disseminates vital information to the aviation community. Many of us know the ASRS as the avenue for self-reporting safety events. However, the ASRS is the perfect reporting point for errors or omissions in flight data, weather data, publications and charts, ATC procedures and published data, and the like. Don’t sit on the data: Log on and tell them about it soon!

Imagine you’re the aircraft commander of a C-130 Hercules flying at night into a forward landing strip way out in the Iraqi sticks. After carefully checking NOTAMs and weather data, imagine your surprise on landing rollout when your aircraft suddenly plunges into an 86-foot-wide and 2-foot-deep construction hole gouged into the runway. The C-130 is totaled, and nearly everyone is injured, but nobody died. The Accident Board President said, bottom line, the Army airfield commanders and managers didn’t follow any of the procedures for NOTAMing this airfield construction or marking the runway as unusable.

I for one have great faith in the information available to us pilots and builders. In fact, given today’s digital nature, NOTAMs and weather data updates get to us more quickly and accurately than ever before, especially if you have ADS-B feeds or tablet-based services in your cockpit.

So, you can have hair or you can have brains: Either way, you’ll have to pay. You can spend the time and energy to gather all the info you need to plan a safe successful flight. Or you can do nothing.

Ever been smacked by a bald gorilla?

Note: All references to actual crashes are based on official final publically-released NTSB and Air Force Accident Investigation Board reports of the accidents, and are intended to draw applicable aviation safety lessons from details, analysis, and conclusions contained in those reports. It is not our intent to deliberate the causes, judge or reach any definitive conclusions about the ability or capacity of any person, living or dead, or any aircraft or accessory.