“Where did you get this?” my mom demanded, shaking a thick brown envelope at me. One that had been hidden under my mattress. I couldn’t lie, the guy’s name and address were right there on the tattered envelope: D.L. Burris.

“How do you know this man?”

“I don’t know him. I found that through a classified ad.”

“What? How did you get this?”

“I…I called him from a pay phone and mailed him a money order.”

“You’re only thir-teen! How do you even know about these things?”

“From…Dad.”

“Go to your room until your father comes home.”

I wasn’t worried. I knew where my dad stashed airplane plans in the basement. That gave me leverage. He had plans for the VariViggen and the Hovey Whing Ding II. Mine were for the Evans VP-I.

I’ll confess. That conversation never happened. But the salient facts remain. I mail-ordered a set of Evans VP-1 plans (from one D.L. Burris—how do I even remember that?) as a middle schooler and stashed them in my bedroom. I would close the door and stare at the well-worn pages, memorizing every detail and fantasizing about the day I’d have one. I tried to make that day happen in high school but I was rebuffed by my woodworking teacher who told me to pursue something I could finish during the school year. I countered that I could build the tail as a standalone project but was again rejected. No tail for me. At least not in high school. Instead, I built a stereo cabinet, though a crossbow or black-powder rifle were school-sanctioned options. Different times.

Failed Relationships?

The VP-1 never happened. Not even the tail. Nor did the Graham Lee Nieuport 17, which I started by bending tubes for the rudder. I abandoned that project after a minimal investment of time and money. Next came a stab at a Pietenpol. I’d already designed a paint scheme with a cool, old-timey graphic that incorporated the word “aero” with my last name, so I felt pretty well committed to Bernie’s creation. Driven by that commitment, I bought enough Sitka Spruce, marine-grade plywood and tiny brass brads to build the tail feathers and the wing ribs. Not only was that approach economically prudent, it allowed me to make progress on multiple fronts while the Aerolite glue cured on fixture-bound assemblies.

My first whack at the Pietenpol was short-lived—just days, if that. I was thwarted by the patter of little feet running across the floor above my head. In my dungeon-like basement, I felt miles from my family. When I revisited the project a few years later the wing ribs, wing center section and a fully formed tail developed. But alas, that is where my Pietenpol stalled. Thirty years on, it decorates a basement wall.

Though that may sound like a string of failures, I consider them successes. I learned something from each pursuit. Though fine airplanes all, I learned I didn’t really want a VP-1 or a Graham Lee Nieuport 17 or a Pietenpol. Not enough, at least, to see each project through. I learned about rabbets and rivets and steaming wood cap strips and Aerolite glue. I learned how to fill in gaps in plans and how to choose the correct bolt length for any need. I learned about shipping costs. I learned about being resourceful. I may have learned more about myself than I did airplane construction. I learned I needed to build at home, where I could jump in and out of the project at will. I learned that there are right times and wrong times and right reasons and wrong reasons to take on large projects. I learned an airplane project shouldn’t be driven by a paint scheme. Mostly, I learned.

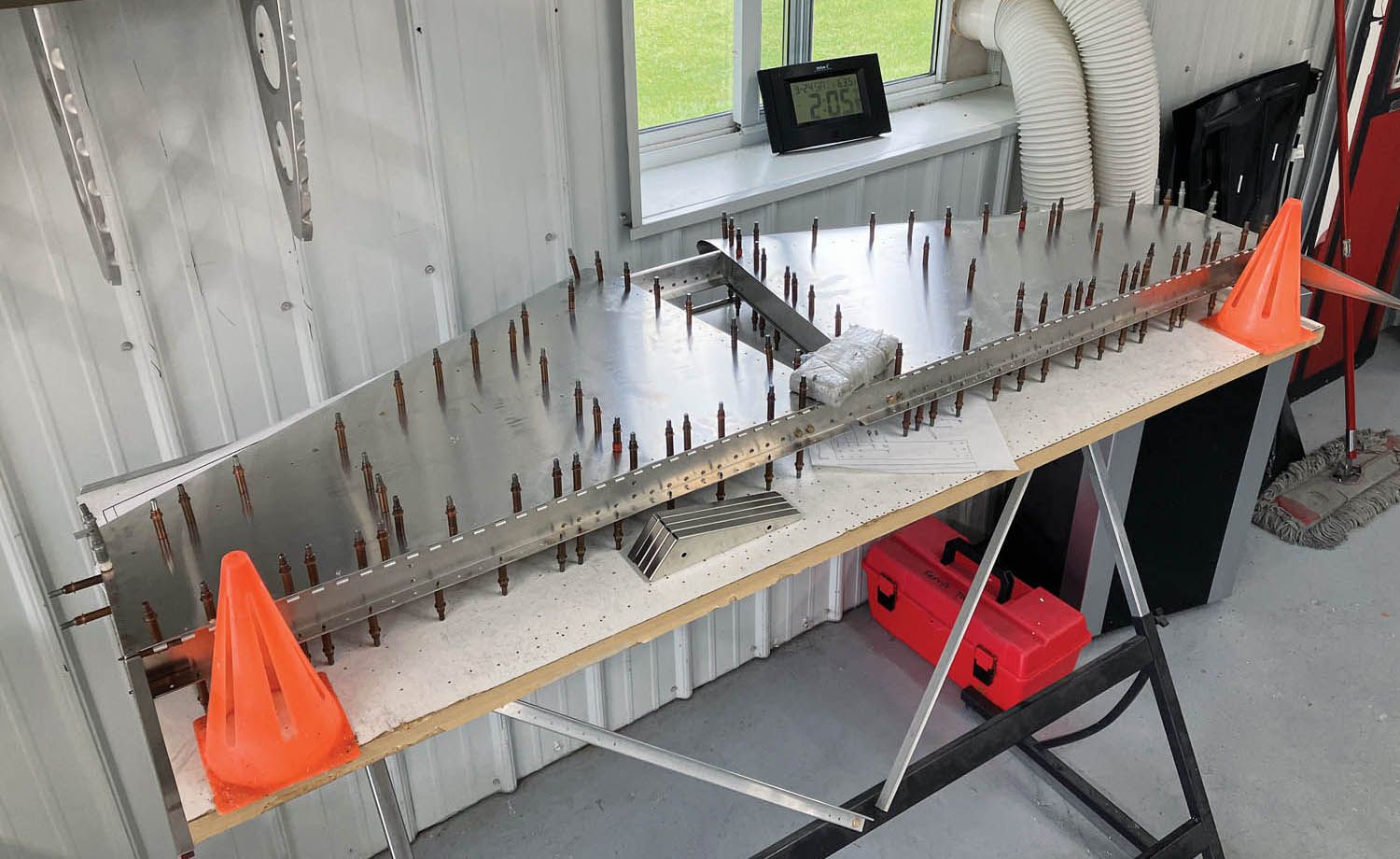

It wasn’t too long after I abandoned the Pietenpol the second time and, frankly, tried to abandon my two-decade-old desire to build an airplane that I was introduced to the still-secret Sonex. Nothing about it except its VW powerplant should have appealed to me—it was all metal, it wasn’t low and slow and did I mention it was all metal? But I was smitten. Impatiently, I waited until the prototypes proved the design was sound and the plans were made ready. At that time, 1998, the Sonex was scratch-build only. Despite my history of unfinished aircraft, I committed to buying all of the raw materials needed to build the entire airframe ($1400 at the time). A bold commitment considering I didn’t have a paint scheme in mind. I began the project by building—what else?—the tail.

Homebuilding’s Learning Bear

It may seem building the tail of an airplane first is an FAA mandate. It isn’t, of course. What it is is an inexpensive toe into homebuilding’s water. If the water proves cold and unwelcoming, one can make a hasty retreat with only a minimal investment in dollars and time. Zenith Aircraft even offers a rudder-only kit for those who wish to test the water before they even change into their bathing suit.

Beginning with a tail kit exposes builders to many of the skills and materials that will be required to build the entire airframe. It exposes a builder to the manufacturer’s assembly documentation, too, which itself can be a learning effort or a deal-breaker for some. In short, tail kits are the learning bear of Experimental aviation. Another seldom-touted benefit of building the tail first is that the assemblies very quickly look like airplane parts, which is tremendously motivational.

Kit manufacturers who offer quick-build airframes (where much of the airframe is preassembled by the factory) often leave the tail for each builder to assemble. Leaving the relatively simple tail unbuilt helps a quickbuild kit meet the FAA mandate that “51%” of an E/A-B be built by amateurs and does so without exposing the builder, who may be new to aircraft construction, to the cost of replacing expensive components should their workmanship fall short. A tail skin is less expensive to buy and ship than a wing spar.

Starting Again. And Again

A number of years ago I thought I wanted a Waiex. Halfway through the tail I realized I did indeed want a Waiex, I just didn’t want to build one. After the unique Y-tail was built, the rest of the airframe would mimic my Sonex experience almost rivet for rivet. I had been there, done that. I craved something different —the way I crave an alternative to driving or flying through Atlanta on my way to Florida. The unfinished Waiex tail joined the Pietenpol tail in my basement for my heirs to discard.

However! After AirVenture 2022, I began construction of a Onex. I began, of course, with the tail. You’d be justified to ask why someone who already built an aluminum airplane from scratch would still start with the tail. Two reasons: It’s hard to hang an engine on nothing and a tail kit answers a question that applies equally to new and experienced builders: “Do I have the gumption to see this through?” That’s to be determined but, to quote Maverick from Top Gun, “It’s looking good so far.” Don’t tell my mom.

Another great piece, Kerry! You’re my favorite columnist, don’t tell Tom Wilson

Thank you Ariana. That’s high praise and I’ll work to live up to it. (Oh, the pressure!)

Blue Skies….

Kerry

Press on Kerry. I have sceatch built a Sonex, rebuilt a poorly built Waiex and now I am flying the Onex I recently finished after a long gestation. We are after all, a group of serial builders frustrated after 20 years of the USAF giving me a C-130 to placate my aviation habit and now having to support my addiction on an old MSgt’s retirement check.

I’ve heard most completed EAB planes were not completed by the original builder. I plan on buying a project plane for my first adventure into EAB building. I also plan on having an airworthy plane while I build so I won’t get get-her-done-itis!

Great post! I teach incremental finishing as a fundamental skill in modern business, but I never thought of rudder-first as exactly that. Have always been afraid to build an airplane. Bought plans and a rebuildable engine for a Dragonfly in my 20’s. Owned a ’41 T-craft for a time. Now in my 60’s, maybe a Europa or Sonex tail is next for me??

Thanks for your inspiration!

Hi Marc,

Thank you for reading my column I’m glad you found some inspiration. Building an airplane is only hard if you take on the project for the wrong reason. A tail kit is great way to discover if your reason(s) for building is well-placed. The actual building process can be very repetitive: bending metal, drilling holes, setting rivets, sanding fiberglass, deburing edges, and on. The skills themselves are pretty straightforward. At age 60, you’re still a youngster in aviation.