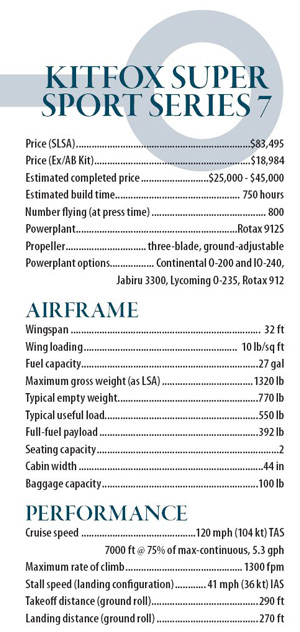

After 25 years, the Kitfox has graduated. Not that the design found itself struggling through advanced education. Indeed, only the previous company had trouble with Econ 101. Nor are we suggesting that the Kitfox, in its latest Super Sport guise, needed to pick up a few extra credits—the kit is well rounded and mature. Instead, the news from Idaho is that the Kitfox has matriculated into postgraduate work as a ready-to-fly Special Light Sport Aircraft (SLSA).

This achievement is significant on a lot of levels, including those of interest to homebuilders, because while Kitfox Aircraft, under the able direction of John and Debra McBean, has completed the task of getting the Kitfox to series production, the move is an enabler in other ways. Think about it. A diversified company is a more durable company. Should kit sales slack off—as they have for just about everyone in the industry—SLSA sales could potentially keep the workforce active. Conversely, income from the SLSAs will help fund development of the kit aircraft and subsidize that end of the business through economies of scale.

But that’s at the other end of the campus, so to speak: Right now, Kitfox Aircraft intends to build just six SLSAs a year from its collegial headquarters at the Homedale, Idaho, airport. John McBean says that the company could produce a few more, maybe as many as one a month in the existing facility. A “shovel ready” parcel of land exists to the southwest of the main hangar that could hold another building.

Such volume is unlikely to put a strain on the company’s kit end of the business, even as Kitfox has taken the uncommon step of building as much as possible from local content and in house. Outsourcing is a word that sticks in McBean’s throat: “We’re proud of the fact that we build so much of the Kitfox right here,” he says, waving over his shoulder to the main workshop. There, men bending sheet metal and welding chrome-moly tube form a movable backdrop, highlighted by the gentle thwack of the metal shear or the bzzzt of the welder. Still, there are limits: Kitfox buys landing gear, some CNC-cut wood components and fiberglass work from outside vendors, all located in the U.S.

The engine you might call a foreign exchange student. “Yes, well…” McBean says. “I would love to have an American engine [for the SLSA], but the Rotax 912S is really good, a great match for the airplane and very light. That’s important for us, especially at the lower LSA gross weight.”

How Did We Get Here?

Destination SLSA can be reached by many roads, but the one traveled by the McBeans was remarkably straight and free of breakdowns. It helps that the Kitfox Series 5, then owned and developed by SkyStar Aircraft, had been developed with FAR Part 23 certification in mind. “We have a ton of paperwork and engineering from that effort,” says McBean. It’s fair to say that the paper trail required for a straight Part 23 aircraft is quite a bit more involved than the relaxed ASTM specs demand, and so, he says, virtually all of the burden of proof that the design meets the ASTM specs for such things as structural integrity and landing-gear drop tests was, you might say, preexisting.

“We made a few small changes for the SLSA,” McBean notes. “All of them were in the engine installation, which is an ‘open’ area for homebuilders. We heard of some issues with the oil pressure sender being mounted directly onto the engine. [That’s been standard Rotax practice.] So we designed a remote mount where the sender is on the firewall. We also have a sensor to measure fuel pressure; that would be a builder option on the kit. We also fitted the SLSA with a carb-heat kit, which is also an option for kit builders. The way we read it, Rotax ‘recommends’ a heated air supply in the event of carb icing, and that means it’s smart to use a carb-heat system. Some SLSAs don’t, and I can’t understand it.”

The benefits of creating a ready-to-fly machine extend back as benefits for builders. “Because we already did the work on this installation, which has a lot of other small improvements for the initial installation of the components and ongoing maintenance, we have been able to create drawings and directions for builders to duplicate our firewall-forward setup,” McBean says. For those who might think that series-producing a kit-based aircraft would somehow put the homebuilt on the back burner, here is your countervailing proof.

What About the Rest?

So the firewall-forward package is different—and limited to the Rotax 912 or 912S, where the kitbuilt might also house the O-200 or IO-240 Continental, O-235 Lycoming or Jabiru 3300. But the rest of the Kitfox SLSA is off-the-rack Super Sport Series 7. That entails a sturdy chrome-moly steel-tube structure—optionally powder-coated for the kit, though that’s a standard feature of the SLSA—from engine mount to tail. The SLSA model employs the normal massive aluminum U-shaped maingear structure, bolted to the bottom of the fuselage cage, which characterizes the Super Sport Series 7. For the moment, Kitfox has built its one SLSA as a trike, but will build taildragger versions soon.

“That’s my mule,” McBean says, pointing to a partially completed Kitfox at the back of the shop. It’s a taildragger, of course, but will also be used to test a few new components for the kitbuilt, including a composite wing leading edge. The smooth surface, without the rib humps that adorn the current Riblett airfoil, should improve low-speed performance. “Can’t wait to try it,” he concludes.

By most other measures, the SLSA and Experimental/Amateur-Built version of the Super Sport 7 are close relatives, sharing some compelling attributes. For one, the cabin is surrounded by plexiglass to offer a sensation that’s probably only a few notches away from piloting a Breezy for unimpeded visibility. Those flip-up doors are translucent sheets riveted to steel frames, while the roof is similarly sun friendly; look up, look down, your call.

Crikey, What a Panel!

The McBeans built the first SLSA to the highest specification offered in the abbreviated line, which starts with a needle-ball-airspeed version that’s quite basic for $83,495. The airplane we flew packs all the options—cabin heater using the Rotax’s coolant as a source of BTUs, wheelpants, full interior with nifty under-seat storage bins and a sophisticated avionics package.

Let’s remember that the Kitfox is a VFR airplane. Try to, anyway, as you stare at the Advanced Flight Systems combined EFIS and engine monitor. It might seem out of place in a purely recreational vehicle until you realize the benefits it brings, such as placing all of the critical information in one place, including engine-monitoring functions. It also has an angle-of-attack indicator, and offers a very cool weight-and-balance calculator to help with loading equations—all in a surprisingly light and space-efficient package.

The AF-3500 is the central component of the “Deluxe Glass” option package for the SLSA, a $9850 add-on to the SLSA’s base price. This package also includes a Garmin SL40 com radio and GTX 327 transponder, a PS Engineering PM3000A intercom and an Air Gizmos panel dock for the Garmin X96 series portable GPS. (You supply the GPS itself.) Kitfox is also making dual Advanced Flight displays an option, as well as similar Dynon Avionics components.

Look, There’s an Outside Outside

It might take some effort to pry your eyes off the inside glass to look through the outside glass, but you’ll be richly rewarded. For just banging around in the sky, following rivers and canyons, taking a speed-is-no-concern local trip, the Kitfox is nearly without peer.

To begin with, the design is utterly at home hovering over the scenery at 55 to 60 mph—top of the green arc on the airspeed indicator is 48 mph—with the Rotax pulled back to a fuel-sipping state. Or you can crank it up to get somewhere. Our recent exposure to the SLSA version extolled a 100-mph TAS cruise at less than 5000 engine rpm at a density altitude of around 4000 feet. In that context, the claimed max cruise of 120 mph TAS seems well within reach. Figure that the 912S will burn 5 to 5.5 gallons per hour at normal cruise. Claimed max speed is 125 mph TAS, well clear of the LSA limitations.

True, most aircraft will remain aloft at the bottom range of the airspeed indicator, but few feel as comfortable doing so as the Kitfox. Pitch response is on the light end of the spectrum, but the aircraft absolutely has positive pitch stability. It seeks trimmed airspeed quickly after being upset—intentionally by the pilot or merely by the atmosphere—as long as you haven’t moved the flaps. Because the Kitfox today, as it has done for 25 years, uses near-full-span flaperons for roll and low-speed improvements, there are substantial trim changes with flap deployment. (Early Kitfoxes used the flap position as trim.) This model trims the leading edge of the horizontal stabilizer through an electric jackscrew, whose action is slightly too fast in cruise but about right in the pattern. Overall, aside from configuration changes, the Kitfox presents a commendably light workload for the pilot.

What those flaperons might do for trim changes is more than compensated for in roll lightness and authority. Balance is the keyword here: Roll is lighter than pitch, and the airplane seems eager to remain coordinated as long as you’re eager to move your feet. It is not a shoes-on-the-floor airplane in terms of yaw response, but neither is it a Travel Air biplane.

Takeoff, Land, Let’s Do It Again

In the nosewheel sample we tried, the Kitfox is easy to get comfortable with. Approach speeds are modest—60 mph works just fine—and once you’ve learned to reach for the trim switch (now featuring a trim position indicator as part of the EFIS) whenever you reach for the flap handle, it’s all good. The Kitfox rolls on 6.00×6 main tires and a 5.00×5 nosewheel, so it’s forgiving of uneven pavement, gravel and pilot limitations. The airplane’s pattern handling reflects its weight, so on a choppy-air day the pilot will be relatively busy. With 132 square feet of wing, max-gross loading is an even 10 pounds per square foot; for the kitbuilt version, which can go to 1550 pounds with the optional heavy-duty landing gear, that’s still just 11.7 psf.

Plentiful thrust, a lot of wing, an efficient three-blade composite prop—together they make for an airplane willing to get off short (claimed is a 290-foot ground roll at an unspecified weight) and sneak in where bigger airplanes fear to tread (stated landing ground roll is 270 feet). Rate of climb maxes out, so says the book, at 1300 fpm. The day we flew it was cold but bumpy, so the 800 fpm out of Homedale’s 2100-foot elevation at an airspeed well above best rate is still an impressive performance.

McBean is understandably proud of the measures the company has taken to keep the airplane light. The factory demonstrator weighs 789 pounds empty (typically equipped, your Kitfox will likely be closer to the claimed 768 pounds empty), a figure that puts “useful” back into useful load. Call it 552 pounds total, or 394 pounds payload with the full tanks (27 gallons). A 9-cubic-foot area behind the comfortable seats provides a remarkable amount of luggage space, and is rated for 100 pounds. Clever “headset pockets” outboard of the central baggage bay help keep the cockpit tidy between flights. One benefit of a mature design is that all the clever ideas your builders have tried over the years can show up in production versions. How’s that for payback?

What the McBeans and company have managed to do with the Kitfox since buying the company out of bankruptcy three years ago is actually pretty amazing. Previously disrupted builders are working again, gradual modifications are coming to the kit aircraft, and this new ready-to-fly program was launched in an intelligent, conservative way. John is not betting the company on selling 100, 200 or 500 Kitfox LSAs a year; he hasn’t leveraged the company out onto a limb to beat Cessna and Flight Designs in an already crowded market. No, he’s happy to take a small piece of a hopefully growing pie, and allow the endeavor to keep his staff busy and his kit product supported. That philosophy alone is smarter than a whole room full of MBAs.

For more information visit www.kitfoxaircraft.com.