This has always been true: Airframe design is held hostage by the engine. In the days of the Wright brothers, the Flyer would have been impossible had the boys not endeavored to develop their own powerplant. In every epochal cycle, the catalyst for change has been a new engine technology, brought by economic necessity or the exigencies of war.

For the last quarter century, the Experimental/Amateur-Built movement has been carried aloft largely on versions of certified aircraft engines, which is partly because they’re widely available and “reasonably” priced when all the issues of installation are taken into consideration. (We aren’t saying they’re cheap by any measure.) And, in particular, the industry is well served in the 125- to 300-horsepower range. On top of all that, the airframe manufacturers, succumbing to the desire to produce a marketable product, have leaned toward certified engines as the least-obstructive path to sales. Because of that, you are often left, literally, to your own devices to produce a viable auto-engine (or non-certified engine) flyable package, a fact that many builders have underestimated.

The Falconer V-12 engine was the powerplant of choice for the Thunder Mustang. Based on two GM V-6 engines, the 640-hp brute cost $55,000 in 1997.

Alternative Engines=Hot Property

Yet, the alternative engine movement has provided a strong undercurrent in our world, and for many the possibility of installing an alternative to the seemingly dinosaur-like Continentals and Lycomings (and Franklins) is too primal to ignore.

For most, it’s not just dollars and cents (though the chance of finding a good core engine from a donor car, rebuilding it, mildly modifying it, then bolting it to the firewall for a fraction of what the traditional engine costs is irresistible) but the challenge, too. Spend much time with any alternative-engine builders, and you get the sense that doing what others haven’t, making their project a true one-off, is an alluring component of the chase.

In the August 1987 issue, KITPLANES® offered one of the first of its longstanding directories—table-like listings of components and suppliers that we now refer to as Buyer’s Guides (same dog, different spots)—of auto-engine conversions. The list is a who’s who of the genre: Geschwender Aeromotive, Limbach, Porsche Aviation Products, Revmaster, Javelin, HAPI and more.

When you break it down, the auto-engine conversions separate into VW-based designs (HAPI, Mosler, Limbach, Great Plains, AeroVee), big-inch Detroit V-8s, Subaru flat-four and flat-six engines, the evergreen Corvair, Mazda-based rotaries, and a few examples of car and motorcycle engines from Honda, Suzuki and others.

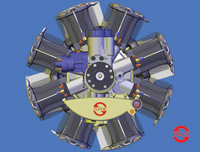

Plus we find the oddballs, like the torpedo-engine DynaCam—certified, flown for awhile on a Piper airframe, occasionally resurrected, and now dormant—Bombardier’s own stillborn high-tech V-6 engine (originally a car engine, but developed very far toward being a purpose-built aero engine) and the infamous Zoche diesel radial. We can shine the flashlight of defeat toward Continental and Lycoming, too; the NASA-funded GAP engine from Continental (a four-cylinder, opposed heavy-fuel engine) never got past the testing stages, and Lycoming has tested and been talking about a Jet-A-burning engine for years.

Once dubbed “the engine of the future, and it always will be,” the long-in-development Zoche diesel radial was displayed at airshows for decades.

Development Requires Dollars

Many of these alternative engines—and not just the auto conversions—failed to gain a foothold because developing them requires a huge infusion of money. Simply put, if the core engine isn’t, by nature and design, close to what is needed for aircraft use, developing the modifications necessary to make it so has proven to be out of the grasp of the small manufacturer. That’s precisely why we see the VW design so prevalent—its natural shape, weight and power output are right where they need to be for aircraft use, so we have decades of companies taking the VW design and improving upon it for aircraft use. Today, the VW-based engine is extremely well developed, particularly in the AeroConversions AeroVee guise, the range of Great Plains systems and, for rotorcraft, in the highly modified RotorWay Exec engine, a liquid-cooled, FADEC-managed opposed four that has virtually nothing in common with the Vee Dub itself.

We have also seen the Corvair well developed into aero-engine form. It is massively helped by being about the right shape, size, weight and power output for aircraft needing about 100 horsepower. It also starts cheap enough that even with modifications it’s affordable.

Computer-managed systems and materials improvements have given new life to the Mazda/Wankel rotary. While Mistral has been on the verge of certifying and producing its highly developed rotary engines, enterprising homebuilders have been fine-tuning Mazda-based installations to fully reap the benefits of this light, compact engine design. (More on rotary conversions in an upcoming issue.)

Alternative engines can be viewed from various perspectives, of course. While the old-school builder typically wants to find the least expensive engine that’ll fit and modify it as necessary for aircraft use, we have seen, in the last 25 years, the emergence of new designs that started life intended for aircraft.

Rotax is the overdog, and who knows what our world would look like had the 912 never been developed. This 80- to 100-hp engine family (plus the 115-hp turbocharged 914), is a key player. Jabiru is quietly doing well with the 120-hp 3300. In the 25 years that KITPLANES® has been publishing, several promising engines have been announced but never really produced. A few we’re still more than a little bit hopeful for must include the DeltaHawk V-4 diesel, the UL Power four-cylinder, and the aforementioned Mistral. Beyond that, we’re keen to see electric motor and battery technology mature for Experimentals. Who knows, by the time we’re writing up our 50th Anniversary stories, the Continentals and Lycomings may have the quaint air of the Wright brothers’ first efforts. You never know.

Kitfox Turns 25

KITPLANES® is not the only organization celebrating its 25th anniversary this year. Kitfox Aircraft LLC has also hit the quarter-century mark, most recently under the tutelage of owners John and Debra McBean.

Dan Denney crafted the first Kitfox and introduced it at Oshkosh in 1984. Conceived as a lightweight two-place STOL aircraft that would use a two-stroke engine, the Kitfox has come a long way since then, while remaining somewhat true to that original mission. In 1992, development began on the Model 5, and an 80-horsepower Rotax four-stroke engine became an option. This new design offered more baggage capacity and more useful load for those seeking back-country adventures. During the late ’80s and early ’90s, the company was selling 40 kits a month, John McBean says.

The Model 6, 7 and Super Sport came later, each offering more capability as well as a variety of powerplant options including Lycomings, Continentals and Jabirus. Today’s Super Sport offers up to 150 pounds of baggage capacity (dependent on center of gravity considerations), and has a maximum gross weight of 1550 pounds. The evolution continues with the imminent introduction of an SLSA (factory-built Light Sport Aircraft) version of the Kitfox, which is scheduled to debut at Sun ’n Fun.

The Kitfox demo plane. The SLSA version will look very similar.

An ardent builder and enthusiast even before he acquired the company, McBean is a long-time fan of the Kitfox. “It’s very versatile, and the focus is on utility,” he said. “It has a folding wing and can be a tri or tail configuration. But it’s also refined, and can be a great cross-country cruiser or back-country airplane.”

The avionics package is also changing as customers clamor for more sophisticated technology in the cockpit. Although it may seem surprising to have glass-panel technology in a low-cost kitbuilt, that’s the wave of the future. Certainly builders can use the standard six-pack, and the base-model SLSA is set up for analog gauges, but two Advanced Flight Systems EFISes are in the upgraded version of the SLSA. The factory demo kit aircraft employs a pair of Dynon EFISes.

Production of the second SLSA was underway as we went to press. Asked if the company would have to gear up production if the SLSA took off, McBean said, “I hope so. But we’re ready.” He credits his skilled, experienced employees for contributing to the long-term success of the company.

Overall, despite some ups and downs over the years, things have worked out well for the company. “The engineers did a great job,” McBean said. “We have a proven design, a huge track record, a good safety record, and good builders manuals and 3-D exploded view drawings that are evolved beyond the competitors’.”

Kitfox also has a customer base that’s like family. “They are a great group that likes to have fun,” McBean said. “Our passion for the Kitfox hasn’t changed, or if anything it’s grown stronger. I see a bright future ahead.”

—Mary Bernard

TIMELINE AUGUST 1988 – OCTOBER 1988

August 1988

In the “Letters” page, Ted Setzer, president of Stoddard-Hamilton, takes Lancair founder Lance Neibauer to task for denigrating room-temperature composite fabrication (in an earlier letter to the editor). Setzer explains that the company abandoned oven-cured prepreg parts in favor of a wet-layup system because it is a superior system and delivers the best airframe construction to the homebuilder.

In “Around the Patch” an item announces the impending debut at Oshkosh ’88 of the Infinity One two-place composite canard from companies located in the San Diego area. Powered by a Mazda-based rotary engine, the Infinity One claimed an expected cruise of 275 to 300 mph, climb in excess of 1500 fpm and a range of 2000 s.m. on 210 hp.

Ultralight fliers as test pilots? Dave Martin’s article explains how those who fly ultralights are in effect taking on some of the responsibilities of flight testing. On the first few flights, the pilot is like a production test pilot, determining whether the specifications meet the actual performance numbers. He advocates gaining experience in the type of aircraft beforehand, doing a thorough preflight and having a plan: Plan the flight, then fly the plan.

September 1988

Here’s an item from the “Builders’ Bookshelf” that may come in handy if the FAA’s new guidance for commercial assistance/fabrication becomes more restrictive: Propeller Making for the Amateur by Eric Clutton. Says the short review, “Designed for the amateur builder, the books assumes no prior knowledge, but the author warns that making your first laminated wooden propeller will take 30 to 35 hours.”

Among the new products in this issue is the Stormscope Weather System from 3M Aviation Safety Systems. The Stormscope’s two new weather-mapping systems chart thunderstorms by “detecting, measuring and correlating electrical and magnetic discharges in the atmosphere.” Stormscope also detects intracloud lightning, and the WX-1000+ indicates turbulence and wind shear. Prices: $8995 for the WX-1000 and $9995 for the plus version.

October 1988

It is announced in “Twice Around the Patch” that Prescott Aeronautical, which marketed the Prescott Pusher, is quitting its Wichita, Kansas, operation. The company was being sold to an Australian outfit, which offered no plans about further development of the design.

“Patch” also reports that Molt Taylor of Longview, Washington, is seeking financial backing for his latest flying automobile. Taylor’s Aerocar was developed in the 1950s, but it never made it into large-scale production. The first of his new kits were to be powered by a 420-hp Allison turbine engine and a pusher prop, which would yield an estimated cruise speed of 165 mph. Less expensive piston engines would follow.

The cover subject this month is the Lancair 320, which is the longer, larger, more powerful version of the Lancair 235. Unusual for a composite aircraft, it is painted bright red.

LeRoy Cook celebrates the BD-4’s 20th year as an American kitbuilt aircraft.

Dave Martin reviews Electronics International (EI) and Masten Products Inc. (MPI) engine analyzers that monitor EGT CHT and oil pressure. Alarm and clock functions are also included on the MPI unit.

A full-page Lancair advertisement runs a side-by-side comparison of the Lancair 320 and the Glasair II, claiming an overall savings on the Lancair kit of more than $4400 (on a total price of $20,760).