West coast experimenters have been warming to the Mojave Experimental Fly-In, and for the event’s second year of widespread promotion by Fly-In major domo Elliot Seguin, a record-setting “speed week” was added.

The core idea was to save record-attempting pilots a few dollars by having official National Aeronautics Association observers at Mojave for several days before the Experimental Fly-In. One advantage of this arrangement is the popular 3-km and 15-km courses need be laid out only once by the observers. Even more practical, because record-setting pilots are responsible for the official observers’ travel and lodging expenses, plus equipment rentals, pooling those bills among several participants promised meaningful cost savings, thus encouraging record attempts and, most importantly, the experimentation that goes along with them.

Record setting is a team sport, although the pilot gets all the credit. Crew chief Mike Brown of Mountain Aire Aviation, Inc. and pilot Lee Behel review engine data on record day; a busy man, Behel relies on Brown for much of the GP-5’s preparation.

And it worked, Tom Aberle, Lee Behel, Mike Patey and Zack Reeder all ran for records at Mojave, with Tanner Yaberg setting a point-to-point record getting to Mojave from Napa Valley in his RV-7A. Due to the inevitable schedule conflicts and Mojave’s often ferocious winds, what was originally conceived as a speed day immediately prior to or in conjunction with the Fly-In turned into something more like a speed week plus a day or two. So, in the end Fly-In participants on the big Saturday event weren’t treated to hot rods launching into the wild blue in county fair main event fashion, but the aircraft and crews were on hand for inspection.

Mojave’s 2800-foot elevation is not ideal for some record setting such as the time-to-climb due to thinner-than-sea-level air, but given a cool morning it didn’t bother the GP-5 enough to matter. Behel wheels it on after the TTC to download data and take on more fuel.

Preparing to Set Records

If the record setting was a little strung out, that’s par for such events. By nature record setting is a near solitary affair, with the time table set more by the team’s and aircraft’s readiness, plus the weather. In practice, the teams set-up shop on the Mojave airport, the planes were fitted with the NAA’s compact GPS tracking devices, last minute fueling, weighing, and other preparations were made, and then the attempts flown when the weather looked most favorable.

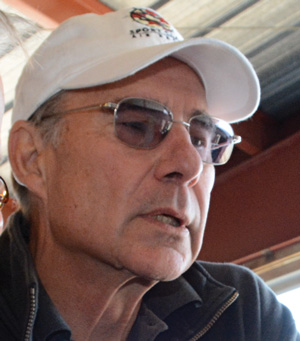

Brian Utley was one of two NAA observers involved in the Mojave record-setting week. Along with Kris Maynard, the pair was responsible for overseeing all Mojave record attempts. Here Utley checks barometric pressures compiled from NOAA sounding balloons by the University of Wyoming. It’s his go-to source for pressure correction information.

For Lee Behel that meant when the rocks weren’t flying sideways in the howling winds. Faced with an overseas trip in the days just prior to the Fly-In, Behel brought his Chevy-powered, one-off GP-5 to Mojave a week early. He was after the 3-km, 15-km and 3000-meter time-to-climb records in the C-1b class, and his schedule meshed with our availability, giving us a chance for an inside the hangar look at his effort.

Besides his crew, chiefed by Mike Brown of Columbia, California, the central figure to Behel’s attempt was NAA observer Brian Utley of Minneapolis, Minnesota. While there as an impartial, official observer and final arbiter of any questions, Utley is also an enthusiast and works freely with all record setters on both the official requirements and the finer points of obtaining the best results. With its heavy reliance on GPS data, Utley’s work on record day centers on obtaining detailed barometric pressures used to correct the raw aircraft performance information to standardized conditions. It’s a process that takes anywhere from several hours to days, but usually doesn’t change the numbers appreciably, so competitors quickly have a good idea if they’ve set a record. This is all laptop work, so Utley took station in the back of the same hangar Behel was housing the GP-5 in. This allowed rapid and frequent communication between he and Behel.

Utley is also the person charged with laying out the various courses, something he does with Google Earth mapping sites and his own overlays. The courses can run however Utley sets them up as long as they follow all the usual regs, with a major emphasis on easily identifiable landmarks for the busy pilot’s ease of locating the course. The time-to-climb was, by definition, directly over the Mojave airport; the horizontal 3-km sprint was originally going to be down the main runway at Mojave, but was moved to just east of the field due to automotive time trials that day; the 15 km was alongside a notable north-south highway immediately west of the airport. Waivers are obtained by each record-setter from the FAA for breaking the 250-knot speed limit below 10,000 feet and anything else appropriate, something Seguin did his best to assist by priming the local authorities on the unusual volume of speed record attempts coming their way.

Weight is a critical variable in both categorizing record-setting aircraft and their performance. All participant aircraft are carefully weighed, perhaps multiple times if multiple attempts are made. Because the GP-5 fit right in the middle of its 1,100–2,200 pound C-1b weight category, observer Utley only needed to calculate the fuel weight after its initial weighing, such as during this 35-gallon fueling between the time-to-climb and 3-km/15-km flights.

Behel’s Record-Breaking Attempts

It can be said that Behel’s attempts began the night before over rice and beans at the local Mexican eatery. Behel’s small crew, Utley, and a few hangers-on such as ourselves piled into every available pickup and rental car for the short ride to dinner, where before and after tostadas Behel and Utley briefed each other on the details and logistics of getting everyone where they needed to be the next morning. For Behel that meant the pilot’s seat of a lightly fueled GP-5, for Utley it was almost anywhere he could watch, especially the aircraft fueling because it figures in the all-important weight classification. With no need for timing lights, stopwatches, high-speed cameras, or other old-school speed-measuring tackle, his exact location was immaterial.

Behel’s record day dawned gritty brown with winds gusting over 40 mph—too energetic for record setting. By mid-morning the wind was down a notch, no longer threatening to detach the windsock from its moorings and within the experienced Behel’s capabilities in the GP-5. But it promised a hammering ride—and it was at +5/-3 g.

Clean from any angle, the GP-5 arrived at Mojave ready to run and required only typical maintenance during its speed trials. The white patch is an NAA-required GPS antenna attached for the time-to-climb, 3-km and 15-km dashes. The GPS battery pack, receiver, and antenna were rented from NAA and were shared between Behel and Tom Aberle.

First attempt was the 3000-meter time-to-climb. Behel had just enough fuel on board for the two-minute climb, plus the usual taxiing and a bit of a reserve, but not enough to keep the fuel pickup from unporting at the top of the climb. But it was enough to reach 10,000 feet, and within minutes the GP-5 was back in its borrowed hangar being refueled for a single flight, back-to-back attempts at the 3- and 15-km speed dashes. In the meantime Utley downloaded his GPS data from the airplane to his laptop, gave it a quick review, and announced the two-minute-flat effort was easily within the existing 2:20 record set by Bruce Bohannon. A quick cheer, big smiles and it was back to work.

As Behel taxied out, most of the crew and observers—but not Utley—scrambled into trucks and into the desert to mark the 3-km course’s entry and exit gates with their vehicles. There was some difficulty finding the pre-marked course—it was one of many dirt roads in an otherwise featureless sea of widely-spaced brush—and we knew Behel would have a hard time picking out the correct course as well.

Racers soon learn contests are won in the home shop and not by demon tweaks at the event. All the GP-5 got at Mojave was a final wax job and a lot of eyeballing by the crew.

Utley had provided several Google Earth prints of the course, and they were carefully studied, but the feature-poor terrain still had Behel hunting for the correct track, even after making a successful pass down the centerline. Two passes through the 3-km course are needed in each direction, which really means running 5 km four times as the aircraft must be level for a kilometer before and after the timed portion. Thankfully the course is a kilometer (.62-mile) wide, so even as Behel ran a bit wide of the centerline, those runs still counted, and after a bit of hunting around, the 3-km was in the bag.

Designed by George Pereira for unlimited air racing, the GP-5 Osprey has found a home with Lee Behel in Super Sport Gold contests. It’s powered by a 6000-rpm, 625-hp naturally-aspirated Hasselgren Engineering small-block Chevy based off a DART block—and sounds just like a hot rod when it rips overhead such as on this 3-km record pass. An EPI EB-1 PSRU off of a Lancair keeps the Hartzell race prop at 2900 rpm.

For us ground observers, that was it. By the time we got back to the hangar, the GP-5 had been up and down the 15-km course four times, was inside the hangar, its GPS data downloaded, with Utley reducing the variables to come up with a close preliminary figure of 372 mph on both courses, and Behel knew he had three new records to his name. As expected, the final figure took a few days to reduce, and bumped the official figures to 377.6 mph in the 3-km and 378.7 mph in the 15-km.

Zack Reeder spent 15 hours surrounded by fuel tanks in the once multi-passenger Catbird. The fuel system was carefully built and extensively tested in the year prior to its record-setting attempt—and it was on display during the Fly-In.

Reeder’s, Patey’s, and Aberle’s Attempts

The tree-tall winglets on Mike Patey’s Lancair were literally just the tip of the modifications to his record-setting speedster. A 780-cubic-inch 8-cylinder Lycoming with centrifugal supercharger, longer landing gear, and larger WhirlWind prop are the highlights, along with blazing new 319-mph records in the C-1c 1000- and 2000-km distances.

For Zack Reeder the story was completely different. Where Behel had made few modifications to the GP-5 specifically for his record sprints, Reeder and crew had been working on Burt Rutan’s Catbird cross-country machine for over a year, updating and prepping the venerable design for long-distance glory. Not the least of the modifications was the design, construction, installation, and extensive testing of a veritable “throne” of fuel tanks surrounding Reeder’s pilot’s seat. They were made necessary by the marathon-like 5000-km (3107-mile) closed-course speed attempt. His course was at altitude, back and forth between Inyokern and Big Pine, California. That’s a slightly bent track up and down California’s Owens Valley for a rump-numbing non-stop 15 hours. Reeder was solo, in the air at 6:15 a.m., finishing at 10 p.m., and as you’d expect, few were around to witness his record 211-mph average, but it was the major achievement of the speed week.

Though dependent on GPS timing, the NAA observers want backup altitude information from the aircraft’s pitot system. Tom Aberle thus had to add this static port tube as his racer Phantom hadn’t needed one for Reno competition. Not unexpectedly, Elliott Seguin just happened to have a port on hand to get Aberle record-ready.

Mike Patey brought a ton of speed to Mojave with his GSIO-780-EXP powered Lancair. Boundlessly energetic, Patey burned drums of midnight oil modifying and painting the speed-modded Lancair up to the last suspenseful minute, then arriving just in time for the record attempt window. But it was enough to lay down 319-mph records in the C-1c 1000- and 2000-km closed-course events. Ironically, the previous 2000-km record holder was Mike Melvill in Catbird, a record Patey reset by a scorching 62 mph. Patey’s Lancair has both streamlining and horsepower!

Tom Aberle was the only participant to come up short of the existing records in the C-1a 3-km speed and time-to-climb, but then he was flying his Reno biplane Phantom against times set by Jon Sharp in Nemesis and Bruce Bohannon in the Miller Special (both monoplanes). Aberle showed up mainly to set a baseline, as he’d never previously run Phantom for straight-and-level speed, and was off by only eight mph. Now he knows what to shoot for.

Which brings up the most important point: there’s no overwhelming reason why you could not be a contender at next year’s event. Classes are based on aircraft weight, so there is often a place to run, and there are no special pilot or aircraft certification hurdles. There are travel and equipment rental costs; they vary, but count on $2,000 for your share. Like the greater Mojave Experimental Fly-In, setting NAA national and FAI international records is all about innovation and execution. If you’ve got the speed, records are set here.