It’s nice to know that Boeing and Airbus are working on future electric airliners, and that biofuels may power the big aircraft in the interim. But seeing a bunch of homebuilt electric aircraft capturing records and making history renders this writer ecstatic. The fact that three of these organizations are in France makes visiting the Eiffel Tower an imperative.

Pouchellec-A Pou de Ciel (Flying Flea) made with a ladder-like fuselage and powered by a Lynch electric motor.

Lavrand, APAME and Electravia

Overseeing a growing legion of electric vehicle enthusiasts, and maintaining an aircraft design and construction firm; an electric motor, controller and battery development and sales operation; and a propeller company, Anne Lavrand is trs busy, even reporting on her many activities in a near-daily blog. The Organization to Promote Electrical Aircraft (APAME), endeavors to educate and inform its members on happenings in electric flight. With over 400 members worldwide, its environmental concerns are a growing factor in the interest being generated by electric flight.

Corporate concerns center on creating an array of small aircraft powered mostly by Lynch-type motors, a simple brushed unit that requires a fairly simple speed controller. She oversees the parent organization, Electravia, which comprises several related enterprises: E-Motors, E-Props and the online E-Props Shop.

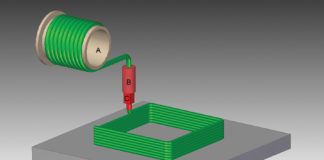

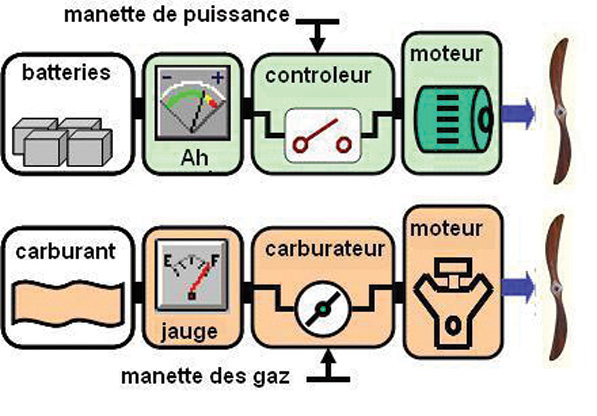

Electravia’s proposed serial/parallel hybrid approach.

With a diploma in business and certificates in aerospace education and "judicial expertise," she works with Christian Vandamme, her chief technical lead, Jrmie Buiatti, lead in propulsion and propellers, and Sammy Dupland, head of E-Props and flight testing.

E-Motors configures and sells motors, controllers and batteries-often complete plug-and-play systems-to clients in Europe, China and North America.

Lavrand claims many firsts and records, including the ultralight Electra flying 50 kilometers (27 nautical miles) in 48 minutes in December 2007, followed by her Electron Libr (Free Electron) trike in June 2008 and more than hour-long flights by an Alatus ME sailplane in January 2009.

E-Fenix shows a four-blade E-Prop with offset blades. These cause “dephasing of sound waves and lower noise.”

Her drive keeps things moving, with a recent world speed record of 262 kilometers per hour for the two-motor Cri-Cri, and topping that very publicly with a 283 km/hr romp down the main runway at Le Bourget for the Paris Air Show.

At a much slower pace, E-Fenix, the first electric two-seater paratrike in the world (there was one in eastern Europe, but never shown with two people on board) has flown with a 35-hp GMPE 104 motor, an E-Props four-blade thruster and a 6 kWh Kokam li-poly battery pack. The wing is a 38-square-meter Bulldog.

Developed with Plante Sports & Loisirs, a leisure activity firm based on Re Island, E-Fenix will carry the pilot and a sightseeing passenger over the scenic region for up to 35 minutes. The E-Prop that propels it lowers the noise level for passengers and those below, making the tour a peaceful one.

Take one of the stalks on the nose of Cri-Cri, attach a 26-hp 104 and controller and top a vintage Fauconnet with it. Couple this with an E-Props propeller, instruments and a 3-kilowatt-hours, 24-kilogram (52.8-pound) Kokam lithium-polymer battery pack, and you have a "poor man’s" Antares. While the more sophisticated Antares will set you back 200,000 (about $285,000), Lavrand says her ElectroPod package will sell for about 15,000 ($21,300). Considering the cheap launches and the low cost of recharges, the economy of the system becomes apparent. "It’s a solution to have an electric motorglider for a reasonable price," Lavrand said, with it providing an hour and 20 minute cruise or a total climb of 3000 meters (about 9600 feet).

The E-Props part of the enterprise makes both two-blade and four-blade propellers, with individual blade segments having optimized airfoil sections for best performance. The four-blade units have a unique characteristic in that the blades are not set at 90 separation, but at an acute/obtuse arrangement.

According to Electravia, on a trike with a Rotax 582, the E2QD prop gave 6% better climb rate, 3 kilometers per hour higher top speed, 8.8-dB noise reduction, and 1.15 liters lower fuel use per hour than the original stock prop. Future plans include a hybrid power system, a two-seat flying wing and an ultralight.

Flying Ladders

The Association for the Promotion of Flying Ladders (APEV) web page is graced by an Elizabeth Montgomery-like witch scooting skyward on a ladder, rather than a broom. Its designers originally used a commercial aluminum ladder as a fuselage to which wings, pilot’s seat, engine and tail feathers were affixed. The company had to turn to bolting and riveting standard aluminum extrusions together when the ladder manufacturer was spooked by visions of lawsuits from ladders falling greater than usual distances.

Early designs were based on Henri Mignet’s Flying Flea formula, a tandem-wing, pitch-and-rudder-controlled configuration that compensated for Mignet’s inability to manage a full-three-axis flying machine. Initially powered by Rotax two-strokes, the little airplanes climbed rapidly, cruised at ultralight speeds and demonstrated acceptable handling characteristics. Moving to electric power, they used a Lynch motor, Kelly controller, and Kokam batteries and propellers from Helix, a German firm.

The bewitching logo for the Association Pour La Promotion des E’chelles Volantes (Association for the Promotion of Flying Ladders).

The APEV has designed and built an aluminum look-alike for the Santos Dumont Demoiselle called the Demoichelle, a pun on the ladder-like frame. Replacing the Rotax with an Agni 112R motor changes its appellation to Demoichellec, a further play on words indicating a ladder-like, electrically powered Demoiselle. A vintage-looking wood box encloses the batteries, and is about the only non-metallic bit on the machine.

Its pair of pivoting wings, eschewing ailerons, roll the airplane to provide lateral control. This makes for simplified wing construction and a lively turn, simplified enough to enable the APEV team to assemble and fly Demoichellec at the 2010 Paris Green Air Show.

The wings show up on APEV’s latest offering, the Scoutchel, a more modern trigear aircraft but with all of the simplicity of the organization’s other creations.

Plans and kits are available for APEV’s creations, with most airframes costing less than $10,000.

LSA’s MC-30 with Jean-Luc Soullier in the cockpit. In the background is the zeppelin with which it shared a hangar at Friedrichshafen.

Aiming for the Record Books

Luxembourg Special Aerotechnics (LSA), chartered in its namesake country but flying for Monaco, has a great set of ambitions according to its founder, Jean-Luc Soullier. Its Colomban MC-30 set two world’s records at this year’s Friedrichshafen Aero Expo, its triumphs witnessed by His Serene Highness of Monaco, Prince Albert II, a "godfather" for the team. In another principality-related event, Soullier intended to fly the first international electric air mail between Monaco and France last September, though conditions did not permit.

As announced on LSA’s web site, "The FAI (Fdration Aronautique Internationale) has released our first record: 13 April 2011 Microlights: speed over a straight 15/25 km course: 135 km/h Jean-Luc Soullier." The maximum altitude part (would be any altitude at which the aircraft flew, because no one else has filed for such a record. Things should heat up in this category of record-setting, however, as the airplanes involved are small, light and, best of all, inexpensive, allowing other motivated amateurs to compete and bring electric aviation to a broader audience.

The team has grand ambitions, seeking to win all world records for an electric airplane in its class and to cross the Mediterranean Sea in homage to Roland Garros, the WW-I aviator who flew from southern France to Tunisia in northern Africa in 1913.

MC-30 in LSA’s workshop, showing simple construction, motor and battery installation. This was designed by a Concorde designer.

The forum moderated by LSA provided a great many insights into the problems faced by those attempting to design electric power systems for aircraft. Soullier and his partners, Marschner von Helmreich and Fabrice Tummers, are forthcoming and open in their assessments of the issues that confront them. They had written about the overheating problems with their past technical partner’s equipment, for instance, and considered various options. Now, according to Anne Lavrand, they have turned to her to install an Electravia replacement, a larger and heavier, but more powerful Lynch motor.

They started even smaller, flying a Colomban MC15, which with its two Plettenberg Predator model airplane motors, "climbed for the trees," if I’m translating the pilot’s remarks correctly. No more testing has been done on this airframe, but if it were to use two Lynches like Electravia’s successful effort, we could look forward to electric Cri-Cri races (a hopeful fantasy on your author’s part).

How Much Does It Cost?

All of the systems shown use the Lynch or Agni motor package, so we can at least give a reasonable cost estimate for the motor, controller and battery system. We’ll omit instrumentation and other options to reflect a basic package, with the caveat that your budget may vary.

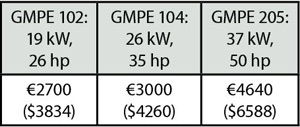

Electravia’s motors come in three flavors, the 26-horsepower GMPE 102, the 35-hp GMPE 104 (as used on the record-setting Cri-Cri) and the 50-hp GMPE 205, the latest offering. All motor prices include the company’s specific Electravia controller. Prices shown are without French taxes included.

Because the GMPE 104 and 205 kick over at 6000 maximum rpm, they require a propeller speed reduction unit (reducteur) to bring the propeller into a more tolerable range. The 104 reducteur costs 1400 ($1988), and the 205 unit 1590 ($2258).

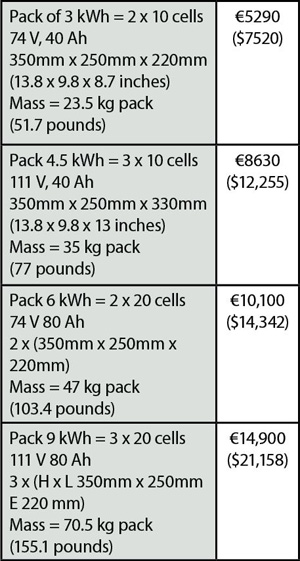

Hooking up the batteries reveals the economic Achilles heel in this approach to budget flying. Batteries are the most expensive part of the equation and the one hardest to come to grips with for most would-be builders. All Electravia battery packs come with PCMs (protection circuit modules, which keep everything within preset temperature and charge parameters) and BMS (battery management systems, which control charging and discharging to individual cells to ensure optimum operation and run times). Weights and pricing are from the Electravia web site.

Component prices allow us to add up a grand total for our electric flier. Taking the middle ground, with a GMPE 104 motor and controller, two-blade prop, reduction drive and a 4.5 kWh battery pack gives a total of slightly over $19,000, with energy storage accounting for more than half of that. Many of these aircraft can be built for less than $15,000, and a few for less than $10,000. Flying for the cost of a recharge should make these airplanes highly desirable.

We can also total weights. Electravia motors and controllers don’t vary much, regardless of kW/hp ratings. The 104 with controller, reduction drive and prop flange weighs 15 kg (33.3 pounds). A 4.5 kW pack adds 35 kilograms (77 pounds), giving a total of 110.3 pounds. Add instruments, motor mounts and possible cowlings, and the total is a bit more than a full-dress equivalent two-stroke. Note that batteries account for twice the weight and twice the cost of the motor/controller/propeller drive combination.

Students at Chartres’ IUT (the university’s technological institute) building a Demoichellec.

With these innovators bringing electric flight to the masses (nothing they produce comes close to the cost of an LSA), we can expect to see increasing interest in these simple fliers. As batteries become lighter and cheaper, this segment of aviation will become even more significant.

![]()

Dean Sigler has been a technical writer for30 years, with a liberal arts background and a Master’s degree in education. He writes the CAFE Foundation blog andhas spoken at the last two Electric Aircraft Symposia and at two Experimental Soaring Association workshops. Part of the Perlan Project, he is a private pilot, and hopes to get a sailplane rating soon.