Legend has it that when the British Spitfire returned from its first test flight, Captain Joseph “Mutt” Summers climbed out of the cockpit, hopped off the wing, and told the waiting engineers, “Don’t change a thing—it’s perfect!” If true, then the Spitfire was a rare bird—almost never does a new aircraft live up to its design team’s hopes and dreams right out of the box. An airplane’s first flight is really a new starting point in the development process—the refining of the design to become everything it was intended to be. This is as true in the Experimental aircraft world as it is in the factories of the great production aircraft.

I thought about Summers as I flew my RV-8 over the Cascades and descended into Oregon’s lush Willamette Valley to fly the RV-15 once again. Although we’d been sworn to secrecy until now, I had been given the opportunity to sample and comment on the RV-15’s handling qualities several times during its development. Now I was looking forward to seeing—and feeling—the improvements in the latest version, the version Van’s was finally happy enough to make public. After my last flight in the airplane, I smiled at Rian Johnson, chief engineer for Van’s, when I said, “I’d buy this one!” His response was, “Well, we’re going to make it better still!” I was looking forward to seeing how they’d do that.

When Van’s Aircraft set out to create a clean-sheet design with a high wing—a major departure from the many successful designs making Van’s the largest kit manufacturer in the world—they had a number of performance targets. The airplane had to be rugged for backcountry operations and it had to carry 1000 pounds of payload, be able to operate off of typical backcountry strips, and carry two people with a significant amount of equipment and other cargo. Importantly, it had to be fast enough to simply get to the backcountry from the flatlands where most people live. But primarily, it had to fly like an RV—balanced, responsive, stable yet maneuverable—and leave the pilot with a smile of satisfaction. No matter how much it carried or how fast it went, if it didn’t “fly like an RV” it wasn’t finished.

The story of the refinement of the original RV-15 prototype is the story of how aircraft development really works. In reality companies never get lucky and have the perfect airplane the first time, the Supermarine 1930s legend notwithstanding. It takes many hours of flying and many thousands of hours of creative engineering to tune an airplane to fly the way the designers want.

KITPLANES was given early, exclusive access to the RV-15 development, and the airplane itself, so we could watch the team work the initial RV-15 into an actual kit prototype. Which, not incidentally, will soon be ready for market. Although the airplane is still to receive a re-lofted fuselage, the wing is ready, the tail is ready, and the relationship between the two is fixed. The team has settled on landing gear that performs extraordinarily well and has done detailed design work to refine the controls and to give it that RV family feel. It’s now time that we tell the story of just how the airplane first flew, how it flies now, and how it will soon make it to the finish line.

Original Requirements

There is always speculation when any successful company undertakes to deliver a new product. Van’s hasn’t released a new model—the RV-14—in close to a decade, choosing instead to refine designs, kits, and production processes while thinking hard and talking to current and potential customers about what they might want in the RV-15. When the news finally broke in 2020 the RV-15 was going to be a high wing, the internet forums lit up with excited builders demanding Van’s “take their money!” But Van’s is nothing if not thorough in scrubbing through requirements and wanted to target a niche that was not already occupied by an existing design—at least one that wasn’t already in series production.

As Van’s embarked on the RV-15 journey, the LSA class of high-wing bush planes had been selling like hotcakes for years. These give two seats for people and enough camping gear to enjoy the backcountry for a couple of days, an attractive proposition. But for many, these lightweight bush planes weren’t enough. You can’t bring a mountain bike with you nor haul game back out. You can’t carry enough gear to set up a base camp for a week, and while these smaller airplanes are decidedly nimble, some of them lacked ruggedness. That’s fine for operating at LSA weights, but add more equipment and you need a heavy-duty pickup, not an economy-minded runabout.

So the RV-15 was sized for generous weight-carrying capability even though it was built around two seats. Many have asked if they could add small seats in the back, and while the answer is certainly “you could,” the people sitting in them would have to be small and short because the baggage compartment was not designed for height. This was a conscious decision to reduce cross-section area; RVs are supposed to be faster than their counterparts and “big” is “slow.” As a result, the RV-15 is closer to a Cessna 170 than to a Cub or Kitfox at the small end or a Cessna 180 at the big end of the scale.

Early Flights

It was late spring of 2022 when the RV-15 made its first flight, cloaked in secrecy until a security camera from the hangar next to Van’s “skunk works” captured the airplane for the internet to see. Van’s made a few attempts to hide the airplane, registering it as an “RV-8X” just to have a little fun with those trying to unravel the secret. The N-number “N7357” sort of translates into the letters “TEST” if you squint hard enough, according to Van’s marketing vice president at the time, Greg Hughes. And facilities were obtained at a nearby private field for much of the early flight testing to avoid curious onlookers with cameras crowding the fence line at Aurora State Airport.

The first flight was made by test pilot Axel Alvarez, with early reports filtering out about a cautiously optimistic team. The RV-15 was a single-seater at the time because the developmental wings had no fuel tanks; instead a boxy 20 gallons of fuel was strapped roughly on the CG in the passenger seat location. This gave the added advantage of a built-in excuse why no one got to ride along to see how it flew, but eventually a new tank was built that fit behind the seats and a right seat appeared.

The prototype was thoroughly test flown, with much data gathered on handling qualities, performance, and stability. Potential improvements in roll, pitch, and yaw were discussed early on, but there was tremendous satisfaction with the completely new landing gear designed by Brian Hickman. No engineer is ever completely pleased, however, and refinements to make the gear more compact were on the drawing board before the initial testing was complete.

We got our first static look at the airplane in early June 2022, before it headed to Oshkosh, giving KITPLANES a head start in understanding this different Van’s design. We had previously been given access to the “Pine Pigeon,” a cockpit mockup made from plywood and scrap, so the configuration was not new to us. But many of the design details such as the landing gear were. We poked and prodded and reported on the airplane in our October 2022 issue as a “development prototype.” As the factory said at the time, this was the RV-15… but before it was kitted, it would have a different wing, tail, fuselage, landing gear, motor mount, and cowl. Other than that it was the real deal!

The airplane was flown in its early configuration to Oshkosh in July of 2022, and Alvarez was welcomed by a sea of eager pilots and potential customers re-creating scenes from Le Bourget when Charles Lindbergh landed the Spirit of St. Louis after his New York-to-Paris flight. No one was in danger of getting hit by the prop this time, but the crowds crushed in soon after shutting down. No question, the RV-15 was the runaway winner of the “Dead Grass Award” at AirVenture that year.

Refinement After Oshkosh

While the prototype did fine getting to and from Oshkosh, there was still much work to do. Most importantly, it didn’t yet completely “fly like an RV.” The team spent months working on the ailerons, chopped a foot or two off each wing, experimented with control system gearing, and tightened up control runs all to make it more RV-like with positive, harmonious control in all axes. These were learning experiences for the team as they prepared to design the final wing, fuselage, and tail, items that would be similar to the original test article but differing enough they couldn’t just be “scabbed on.”

The new wing, by now perfected in shape and area, needed integral fuel tanks. The fuselage had to accommodate moving the wing back 4 inches—helping with center of gravity location as well as giving the windshield more rake. The new fuselage would also accommodate a more compact version of the landing gear, making the floor area less deep. Controls were constantly modified in the search for more precision and reducing slop and to move the flap lever low between the seats. The engine mount was changed to tune the thrust line, and investigations were planned into tail designs for improved handling.

There was much to do—and then Van’s experienced financial difficulties leading to a reorganization. That delayed development significantly, but the RV-15 was never in danger of cancellation. Customer demand was too great and the team had made too much progress to walk away.

How It Flew on Our First Trial

It was early September of 2024 when I received a phone call from chief engineer Rian Johnson asking if I’d be interested in popping up to Aurora for a little flying. Rian had been promising a chance to fly the restored RV-5 for several years, and I had been kidding him mercilessly while hearing things about the RV-15 testing and how I was hoping to fly an airplane that started in “RV” and ended in a “5” before the year was out. Naturally, I had to ask how the single-seater was flying. “Well, it’s still hanging from the ceiling, so I guess you’ll have to fly the other one that ends in 5,” Rian said, and I quickly canceled my schedule for the next day, jumped in my RV-8, and headed across the Cascades without further delay.

Rian Johnson met me with the RV-15 at Independence Airpark, a quiet field away from the bustle of Aurora’s towered, student pilot environment. There we adjusted the seat cushions to give me the view he designed the pilot to have. Honestly, the view over the nose was excellent, despite me feeling like I was sitting in the cab of an Air Tractor. I found this made the view over the nose different enough for a longtime taildragger pilot such as myself that getting the right attitude at the end of the flare took some time to learn. When I flew the updated RV-15 later I used fewer cushions and had better results, but this seat height is still a matter of debate…and personal preference.

The cockpit was utilitarian—this was not a production prototype but rather a proof-of-concept study. But effort had been put into getting sight lines the same as intended for the final airplane to keep reach and visibility the same, and I found the cockpit fit well. At that time, the flap lever was hanging from the ceiling between the two seats, a location that frankly I enjoy.

The airplane was on 6.00×6 tires, quite appropriate for pavement operations and a good match for the airplane when not dedicated to backcountry operations (where 26-inch tires are intended for the design). My flights that day were to baseline the -15 before a major change was made to the empennage. The tail surfaces with the then current stabilator were being replaced with a conventional tail from an RV-10 to evaluate potential handling improvements.

The aircraft as tested had recently gained new ailerons to improve roll handling, and the entire roll channel mechanism had been gone through to remove free play and friction. While it was readily apparent on the ground by pushing on control surfaces and sticks that there is still play in the system, the in-flight handling was quite good.

We flew the airplane twice that day, concentrating first on air work and then on numerous landings to judge the final flare characteristics. Here is an excerpt from my report to Van’s:

“My overall impression is that this is a good aircraft that will benefit from the additional development work and tuning that the design team is currently engaged in. Roll control currently feels quite natural for an aircraft of this configuration and size and is neutrally stable in turns. It is significantly lighter than typical high-wing aircraft in this category, but not so light as to make the aircraft twitchy—it is, in my opinion, at a good point on the stability/sensitivity curve. Stick forces feel appropriate in roll.

“Yaw is good—it requires rudder input for turns (unlike the low-wing RVs in general) but not significantly so, and it felt both sensitive and well-damped—I did not overshoot or oscillate trying to find the right amount of rudder.

“Pitch is still going to require some work and is the target of the team at this point, which is why they will be changing the tail. While the airplane flies fine in cruise and is stable on approach, any change in configuration of the flaps that requires a re-trim, or the beginning of the landing flare, causes an oscillation (it feels almost like a bob-weight oscillation) in the stabilator, which makes it difficult to be smooth in the flare. I would therefore give the pitch channel a C/H rating of 6 for the flare. (See Cooper-Harper sidebar below for C/H ratings—Ed.)

“Combining with the stabilator oscillation, the very nose-low visual picture with the recommended seat height makes the flare height a little difficult to judge for the pilot new to the aircraft. The two things together make the landing tasks more difficult, and lead to a high flare with a dropped-in landing (at least for this pilot), but the very well-designed shock-absorbing landing gear saves the day.

“Flap operations on this version of the prototype were good, but it is difficult to know how much flap deployment is actually being used in each position due to flexibility in the linkages. The flaps rebound significantly under air loads, and I found that while full flaps look extreme with the aircraft sitting on the ground, they weren’t that extreme in flight because of the “retraction” caused by loads. The airplane behaved well in the flight regimes we tried with all flap positions, and pilots need to be aware that trim changes are required with each notch of flaps. This can cause some bobbles when combined with the stabilator oscillation, so late flap position changes on the approach can get exciting. We did several full flap approaches to a missed approach, and the retraction process was sporty (although safe, especially with the robust landing gear).”

Refining the Design

Van’s engineering staff was aware of the issues the airplane had in pitch. In fact the reason we were called to fly it when we did was because they were about to change the tail, and they wanted me to get a feel for why they were changing the tail. The stabilator approach was tried initially to give better tail power in slow flight for short-field operations, but stabilators are notoriously difficult to get right. The plan was to swap it out for what amounted to an RV-10 conventional tail.

Along with the new tail, the team had other changes in mind. The second prototype wing would, of course, have fuel tanks (the plan all along), and in response to numerous inputs from customers and within the team it was decided to make them hold 60 gallons. While no one has to fill the tanks for every flight, having lots of tankage makes it easier to stay in the backcountry without coming out to civilization for fuel. Then there were the already noted changes to the landing gear to make it more compact, moving the wing back, re-lofting the entire fuselage, adjusting the thrust line, and moving the flap handle to the floor.

The beauty of a concept prototype is everyone involved expected to make changes and therefore everyone was open to ripping things apart and trying new ideas. Good engineering is to make changes one at a time, evaluate the results, and then make another change—and the team worked methodically through this process. They had already spent considerable time getting the roll feel right, and while they continued this work, their concentration on pitch was apparent when we flew the airplane again.

Improvements Proved

I was pleasantly surprised when I received a text message from chief engineer Johnson barely a month later on October 24, 2024. They had just flown the airplane with the new tail and other improvements, and the text was accompanied by a picture of a can of grease…meaning landings were now “greasers” with the new tail. Excellent! Johnson said I needed to fly it, but the weather was closing in and I had some travel planned the following week. “Could I come up tomorrow before noon, fly it, and skedaddle back before the storms hit?” I asked. “Sure,” Johnson said, “We’ll be ready for you!”

And so, after a two-hour trip in my RV-8, I settled into the left seat with project engineer Brian Hickman on October 25, 2024, for approximately 1.2 hours. The purpose of the flight was to evaluate significant changes made to the aircraft since my previous flight These changes include:

- An entirely new conventional tail (to replace the original stabilator-based tail)

- Reductions in roll control system friction

- Stiffening of the flap control system

- Changes to the aileron airfoil

- Aileron hinge position (% MAC) change

- Increase in aileron throw

- Rudder changes, including gearing changes and a bump on the trailing edge

- Thrust line revisions

In our flight test report we wrote the following:

“The change in pitch control was apparent the moment I slowed it to approach speed and nibbled at a few stalls. A quick trip to a practice field proved that landings were indeed now easy to grease it on. The previous deficiency had been completely resolved with the change to a conventional tail—pitch is predictable and stable, and the landing task is very intuitive no matter if you are wheel landing, three-pointing, or landing from an approach with power or gliding.”

What Van’s had found was that the stabilator was effectively “bobbing,” with dynamic coupling of the airplane’s pitch rates and the counterbalance installed in the fuselage. The conventional tail made the airplane so easy to handle that I believe I heard a comment from someone on the staff that “I’ve played with my last stabilator!” I rated the pitch channel for all the landings and go-arounds that we did as a 2 on the Cooper-Harper scale. My report continued:

“The roll control is excellent, with more than enough rate available for a non-aerobatic airplane, and stick forces are harmonious with pitch. I never got to the roll stop when doing roll reversals from steep turns in one direction to steep turns in the other because I simply got there before I could move the stick that fast. I doubt that most pilots will ever get to the stop on ailerons the way this airplane will be flown. But… I flew it in no-wind situations, so I’d reserve final judgment until I flew landings in gusty crosswinds.

“Yaw was acceptable but still just a little sensitive. When attempting to center the ball from a slipping or skidding condition it was easy to overshoot, leading to a one- or two-cycle oscillation before nailing the desired flight condition. This might be an artifact of the aircraft still being slightly out of trim in yaw but was cause for more work. Rudder is required to keep the ball centered during turn initiation, and this is acceptable for a high-wing bush plane in my estimation.

“My recommendation to the team was that I personally wouldn’t change anything in the pitch and roll channels at that point—they were quite good, and I would rate them a CHR of 2 as of that flight for all tasks. Yaw is probably a 3 in terms of trying to keep the ball centered in turns, but for takeoff and landing tasks, it is a 2 as well.

“Flap operation was acceptable, but the fairly low flap operation speed (currently 67 knots) might be masking unacceptably high flap lever forces. I felt that the forces required to get Flaps 4 were fine, but if the force increases with speed, it might not be viable at higher speeds. I felt that 67 knots was a bit slow for the top of the white arc, so this warrants further examination. I also felt like there was a definite difference in flap handle travel between the various flap settings—some closer together than others—and it was easy to forget where you were regarding 3 and 4. (We have seen this same problem in the other airplanes—just looking at the lever position, you don’t know which you are in—you have to remember the notches you have counted.)”

Overall, we were very happy with the airplane and stated it is far more mature than some airplanes that are currently available as kits. Van’s understands engineering takes time and effort and the rewards are that RV Feel and Total Performance.

The Current Airplane

Our next opportunity to fly the RV-15 was just before the prototype went into the paint shop before AirVenture 2025. It was a warm but beautiful end-of-June day in the Willamette Valley of western Oregon when Rian Johnson taxied up in the latest version of the airplane and we got to look it over. Since we last flew it in October of 2024 Van’s had built the all-new wing with 60 gallons of fuel plus the new tailcone; that’s the fuselage from the rear of the baggage compartment to the tail. Ongoing modifications to the empennage had rendered the old tail attach points obsolete so it was time to start fresh, lengthening the airplane about a foot in the process.

Changes in the cockpit included a new, longer flap handle on the floor as well as a fuel selector between the pilot and passenger legs, and of course, the fuselage fuel tank (previously in the baggage area) had been removed. This was our first chance to really get a feel for the size of the baggage compartment, and it is quite generous. The cockpit itself is not finalized, with changes to the fuselage that will affect the panel, layout of controls, etc., but the baggage area is more or less set. There are thoughts for a rear baggage bulkhead with slots for bicycle tires— the baggage having been sized to carry two mountain bikes into the backcountry!

While the airplane is close to its final aerodynamic configuration, there is still going to be a new fuselage center section coming, the one with the wing moved 4 inches farther aft. This to sweeten the CG envelope and rake the windshield a bit more. There is going to be experimentation with a jackscrew trim system on the leading edge of the horizontal stabilizer, and this could change the trim system. As mentioned, the new fuselage will also change things in the cockpit—the size, location, and slope of the instrument panel will be tweaked. Seats are being designed (the test article uses seats from another aircraft right now), and there may be some work to optimize the location of the flap lever now that the basic concept has been ironed out. Because of all these changes coming Van’s understandably did not want to show photos of the test article’s interior in this article—leaving a little suspense for the final kit prototype.

So, how did it fly in this configuration? Quite well. We concentrated our efforts on both air work and multiple takeoffs and landings on both pavement and grass. Rian Johnson wanted me to fly it in two different configurations, first with the ballast that’s been installed on the firewall for most of the airplane’s flight time and again with the ballast mostly removed to shift the CG aft. This is how an engineering department expands the airplane’s envelope, opening it up in various directions in terms of CG, weight, speed, performance, and handling.

Removing the ballast lightened the pitch a little, making it even easier to establish a pitch rate (the expected consequence of moving the CG aft), and that made it even easier to make a smooth flare to touchdown. While the original stabilator configuration earned a 6 in the Cooper-Harper ratings, the airplane is now a 2 for any landing type or configuration.

One thing changed with the wings was the shape of the ailerons, but only a little bit. The effect was to make them heavier—but we fully understood how that came about and it’s on their list to return to the lighter roll forces they had on our second visit. This highlights the idea that this really isn’t the time to delve into comparisons of the -15 with every other RV or kit aircraft out there as Van’s is still tweaking the handling feel. But certainly the working prototype is well balanced, and pitch was still both stable and responsive. We did a pitch phugoid to check the stability with the CG moved considerably aft and it damped out the motion in about two cycles. That means it is easy to trim the airplane for approach, and it will stay where you put it as you plan your touchdown point with power. In our numerous landings this time, both on grass and pavement, we could put the airplane on a spot very easily and get it stopped in short order. In other words, it was a well-mannered backcountry airplane!

One thing pilots sometimes forget about backcountry flying is you not only need to touch down slowly in a straight line, you also have to maneuver on the approach. Many backcountry strips are in canyons requiring flying the airplane aggressively just to get to the runway. The many thousands of hours put into getting the RV-15 to “fly like an RV” aren’t just to carry an arbitrary (and nice) set of handling qualities—it is to make the airplane fly effortlessly when you have to fly a blind base leg and pop the wings level for touchdown coming around a corner to the runway. On this round of evaluation flights I tried to ignore the airspeed indicator (other than to make sure we were below flap speeds) and just fly the airplane to the grass runways—which in Oregon are often surrounded and hidden by trees. In this respect, it showed that the work Van’s engineering department has put into various changes has resulted not in just a single good airplane—it has helped them develop a database of what changes do to the airplane’s handling and performance. With this information they can finalize the design to be exactly what they want, and we definitely look forward to flying the finished RV-15 when the configuration is frozen.

Development Lessons

It took nearly three years from first flight of the RV-15 to where Van’s was happy enough with it to let us write about flying it. The airplane still isn’t quite ready for kitting—they have yet to build the final fuselage and call it ready for market—but the heavy lifting of making it meet design requirements and “fly like an RV” is almost complete. Granted, Van’s Aircraft went through troubled times in the middle of that process, but this is still much longer than most might suspect it takes to perfect a design. We have flown other aircraft from other kit companies with similar timelines and stories. An airplane that flies well, meets its performance goals, and works well as a kit is not something you simply whip up—especially when it is outside the box of previous aircraft you have done.

Clear design goals, evaluations along the way as to how you are meeting those goals, and the willingness to make major changes are key elements in good engineering. Sometimes that means delays, backing up, and starting over, but it is evidence of good practice when a company is willing to take the time to get it right.

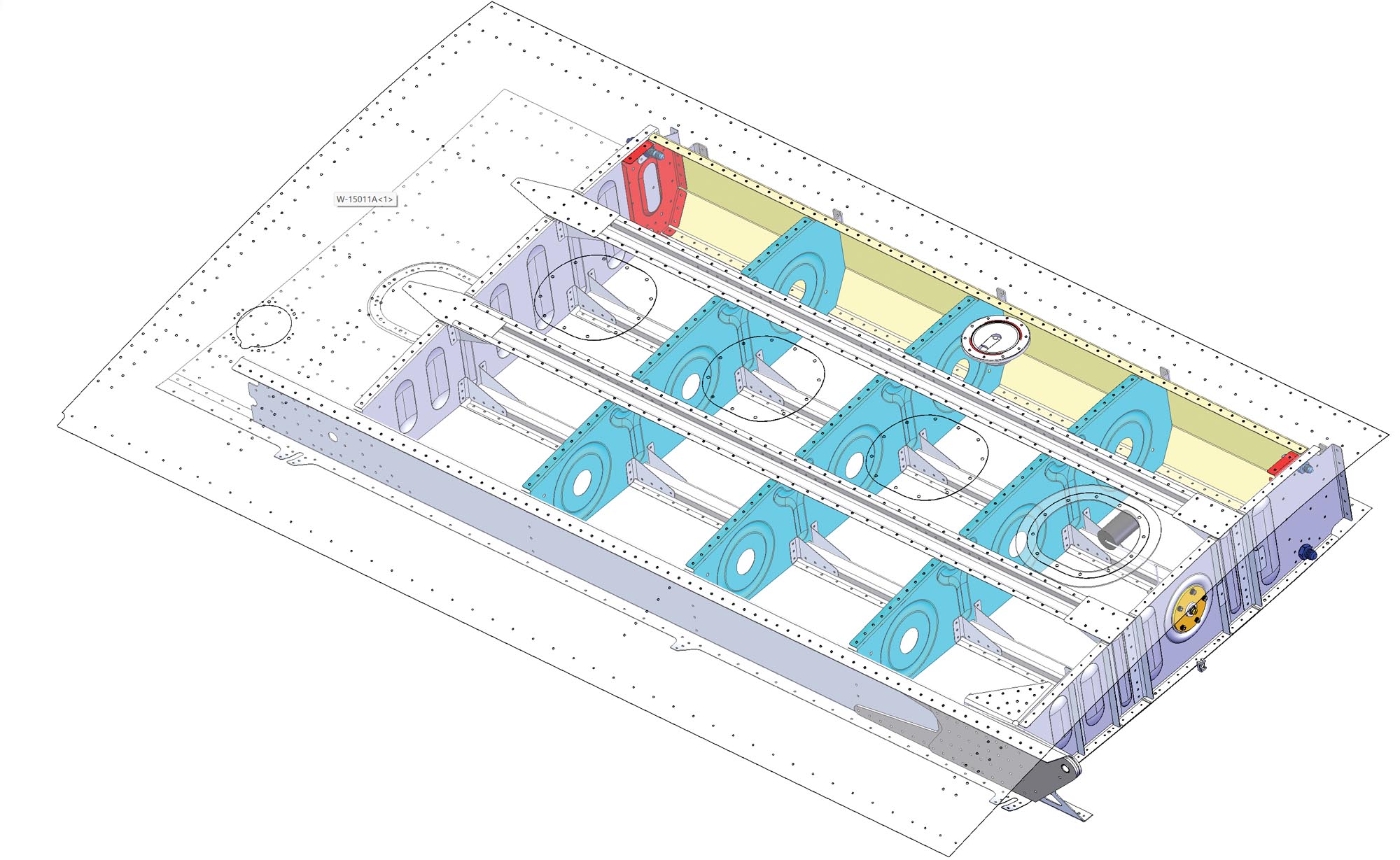

In the modern era of CAD/CAM, prepunched parts, and automated production processes, the design team has to always keep manufacturing in mind—in fact, every part of the RV-15 was designed with final manufacturing in mind, and the parts were produced on the same machinery that will be putting out kits. Hopefully, this will pay dividends when the final design is frozen because all Van’s needs to do is hit “go” on the computer and a hundred tail kits can hit the floor running.

As for me? I better get my current project out of the shop soon—I might just need a new high-wing airplane in the house.

This is a phenomenal writeup. Couldn’t ask for anything more. The low flap speed seems like a huge flaw in an otherwise exceptional design. I hope they don’t release it like that. My Arrow goes 140 kts and flap extension speed of 115 is about the minimum acceptable. Under 100 would be straight up dangerous. Obviously I have a much higher stall speed but still. C172 has an 85 kt flap speed. It would be crazy to be lower than that.

Flap speed limits are not yet finalized as they are still doing some trades on the linkages and levers.

Many thanks for the interesting write-up Paul, including the side bars.

To the lay person (ie me!) the -15 looks just like any other high wing that’s been flying for the last 70 years or more, so it’s an eye opener to understand the design process and challenges.

Hi Paul,

Great article. Do you know if Van’s has any plans to add attach points for floats? I built an RV-7 and it does everything I want in an airplane. If I build another, floats are where I’m heading and I hope Van’s will consider that option.

Thanks,

It is my understadning that there are definite plans to build the RV-15 to be compatable with floats, so I am fairly certain that the apprpriate hardpoints will be part of the standard design.

Comments are closed.