Roscoe Turner, Jimmy Doolittle, A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, and a guy named Sylvester “Steve” Wittman all have one thing in common: They are inductees to the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America. Why? They all gave in to a dire need: speed.

For a midwestern kid with a mild disability born into humble beginnings, Sylvester “Steve” Wittman managed to make quite a name for himself in aviation. You might know him because of the airport named after him, Wittman Regional Airport, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, the site of arguably the largest annual aviation gathering in the world. Then again you might know him because of the plans he sold for the two-seat rapid cruisers he designed and built: the Wittman Tailwind (originally known as The Flying Carpet) or Buttercup. You might not know, however, that Steve Wittman, “Witt” to his friends, was one of the most long-lived, fearsome, and successful pylon airplane racing pilots, well, ever.

The Hopper

It was his need to go fast that convinced him to design and build his first airplane. As a teen, Witt frequented the dusty airstrips where barnstorming pilots hung out.

Wittman used what he had on hand to design and build his first airplane: the Hardley Ableson. This replica is in the Wittman Hangar at EAA’s Pioneer Airport.

“He rode out to the strips on his motorcycle—something else he liked to go very fast on—and spent time with the pilots learning about flying, the airplanes, and how to fix them. And since those WW-I surplus machines were pretty rough, there was lots of fixing to do,” said Jim Cunningham, University of Illinois professor and Wittman biographer. “That’s where he heard, probably from the other pilots, that you had to have two good eyes to be a pilot. Witt had lost sight in one eye as a child. He really never thought he could fly because of that, so he focused on the engineering side and decided to design and build airplanes instead,” he continued.

Even in those days, an engineering degree from a university was a handy tool for an aircraft designer, but Witt’s humble beginnings precluded such luxuries. He just designed and built with what he had, and what he knew. That first airplane? The Hardley Ableson was about as rough as the biplanes Witt studied from. (You can find a replica of it in the Wittman Hangar at EAA’s Pioneer Airport in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.) It had a 12-hp Harley Davidson motor, and according to Cunningham, it never really flew.

Wittman needed a faster airplane. The H-10 Pheasant had a welded steel tube fuselage with fabric covering and a 90-hp water-cooled Curtiss OX-5 engine.

“If he was going across a field and hit a bump he might have gotten airborne for a bit,” he laughed. “After a few of those ‘flights’ the landing gear came apart and he decided maybe it was better to go out and buy something professionally designed,” smiled Cunningham.

Witt eventually learned to fly for real, ignoring his visual impairment, in a WW-I surplus Standard J-1 biplane he and friend Perry Anderson bought in 1924. They found a guy who claimed that he had hundreds of hours in the aircraft (he did, as a gunner, not as a pilot) to teach him. Not such a great plan, but it did work out, eventually. When the so-called instructor up and left town, Witt decided that meant he must be done learning, and at that point he soloed. As he told it in an interview filmed in 1988, he took his first passenger for a ride, a relative, the day after.

And the day after that? “We started our ride-hopping business,” Witt chuckled. Of course there were no pilots certificates issued in the early days of the roaring ’20s, making self-determined commercial pilots pretty common.

Rumor had it that Wittman kept clipping Chief Oshkosh’s wings, but that wasn’t true. Fact was, the airplane had five sets of wings that were used with its fuselage over time.

We Have a Race!

By the time he discovered air racing, two years later, Witt had matured into a pretty good pilot. He studied the action of the souped-up airplanes zipping around the pylons and figured he could do that. So he took the J-1 to Milwaukee and raced it, placing second the first time out. Of course, Witt wanted to win, but the J-1 wasn’t the kind of airplane that even a great race pilot could consistently win with. Besides, with the Air Act coming out, the J-1 wasn’t certifiable. Pilot’s certificates were becoming the norm, as well, and that left Witt with a bad feeling in the pit of his stomach.

Wittman stands next to Bonzo, his 1934 purpose-built racer with a Curtiss D-12 engine, designed to win him the Thompson Trophy.

“The story goes that government guys from this new air agency were going around issuing licenses to ‘certify’ pilots all over the country, and eventually they got to the Fond du Lac area,” said Cunningham. “Witt avoided them, until one day an agency guy caught up with him and asked him point-blank ‘why?’ Witt told him about his bad eye, and the guy was unimpressed. He told Witt, ‘I’ve seen you fly; the bad eye doesn’t seem to bother you,’ and sent him to some Milwaukee doctor who proved it. With that he issued Witt a license with a waiver of demonstrated ability.”

He was a pilot, and could’ve earned a perfectly respectable living that way, but Witt had a problem. He was hooked on air racing, and with a fresh license signed by Orville Wright, Witt needed a better racer. He found the H-10 Pheasant in Memphis, Missouri. The H-10 was designed by Orville Hickman, who made it for Lee R. Biggs, company owner. It was a clean, light biplane, made from a welded steel tube fuselage with a fabric covering and a tailskid, powered by a 90-hp water-cooled Curtiss OX-5 engine.

A new factory-built airplane wasn’t easy to finance, though. Undaunted, Witt decided to become the regional Pheasant sales representative, securing his airplane at a significant discount (ostensibly for demos), according to Cunningham. He flew the H-10 Pheasant to the absolute limit, and he was winning races. Just 11 Pheasants were built, however, before Biggs died in a flying accident on December 5, 1927. Witt helped relocate the company to his home in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin.

Buttercup flew race support for Wittman’s team for years. The original (shown here) was painstakingly restored in 1980 by Forrest Loveley.

A Steady Job

Meanwhile, the folks up the road in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, were looking for a good airport manager for their airfield located off 20th Street, and someone had their eye on Witt. The now locally famous air racer was known to have a steady personality. The way Witt told it, when interviewed, the job wasn’t for him, but eventually, in 1931, he took it, figuring it was a good place to be as he began construction on what would be his first successful hand-built air racer, Chief Oshkosh.

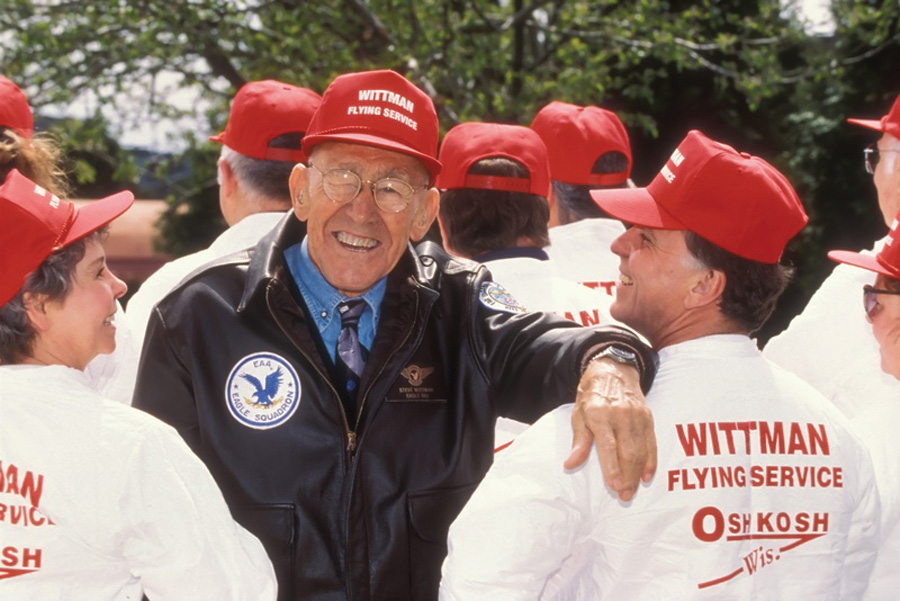

Turns out the job was a career, and Witt nailed it as airport manager, and as the proprietor of Wittman Flying Services (sold to Warren Basler in 1957), for the next 48 years. Oh, yeah, and as a very early member of a little organization called the Experimental Aircraft Association, Witt eventually put Oshkosh, Wisconsin, with that airport off of 20th Street, onto the maps.

Earl Luce’s replica Buttercup is almost identical to the original. LuceAir LLC sells plans, with materials available from Aircraft Spruce. (Photo by FlugKerl2 [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

A Building Fiend

But first there was Chief Oshkosh. This airplane was not the bumbling effort of youth; no, the Chief was the culmination of years of experience flying and studying the other air racers of the day. Witt wanted something light and lean—really just a fuselage wrapped around the American Cirrus engine, with 19-foot wings attached midway up the fuselage and a unique heart-shaped elevator on the tail to keep it all flying. Chief Oshkosh, decked out in red, took third in the 1931 National Air Races with a speed of 150.27 mph, but was plagued with potentially fatal aileron flutter. It was back to the drawing board for Witt.

A year later he returned with a 349-cubic-inch British Cirrus Hermes engine tucked in the fuselage and adjustments to the control linkages that allowed him to push the airplane to nearly 167 mph. It was good enough to beat his nemesis, Ben Howard, at the National Air Races, and later that year to win the Glenn Curtiss Trophy in Miami, Florida. If anyone had doubted Steve Wittman’s ability to either design, build, or fly air racers, they were thinking differently by then.

Wittman’s Tailwind was the first amateur-built airplane to be be certified under the CAR 174-3 rule in 1953; it was the predecessor to our homebuilt certification rules of today.

The records of the 1930s show Witt as a champion on the circuit. To stay on top took constant refinements to the Chief. The wings got shorter (eventually down to a 13-foot span).

“No, he did not cut them off,” laughed Cunningham. “Doing research we found five sets of wings that he used with that fuselage over time.” The wings did get progressively shorter as the engines became more powerful, resulting in predictably quicker race speeds.

In 1934 Wittman created another racer, this time purpose-built for the Thompson Trophy race, which had no limits on the size or power of the aircraft. The machine, dubbed Bonzo, was powered with a veritable antique, the V-12 Curtiss D-12 engine, and again the flying surfaces and cockpit were wrapped around it. Wittman used tightly spaced wooden wing ribs and doped fabric on the wings, novelty construction for a racer at that time. As goofy as the airplane looked (some compared it to a flying barn door), it came in second the first time Witt raced it, in the 1935 Thompson Trophy race. The next year, the airplane didn’t make it to the race, experiencing an engine fire en route to Los Angeles.

Wittman was considered by many to be the father of Formula V air racing. The Witt-V was purpose-built for it, sporting a converted Volkswagen engine.

It wasn’t the first or the only time Witt had to rebuild a racer. Let’s just say ’36 was a tough year. Chief Oshkosh, now sporting a Menasco CS-4 363-cubic-inch engine, doubled spring leaf landing gear, and stubby wings, developed problems during its debut at Nationals and ended up skipping off another airplane and crash-landing.

No matter. Wittman’s shop at the airfield got to work on both airplanes, and they were back racing in time for the 1937 circuit. But here’s the thing—neither racer was really the same.

The Chief returned in 1937 with a single-piece leaf-type steel landing gear that Witt would patent (then license to Cessna), and its tiny cockpit sat up a bit, giving its pilot much better visibility. The aircraft won race after race, eventually setting a new world’s record for its class over a 100-kilometer course at Detroit with a speed of 238.22 mph. But just a year later Wittman hit the dirt in the Chief at the races in Oakland, California. It was 1947 before a revamped airplane with yet another set of wings turned up at the races, and this time the Chief had a new name: Buster.

Bonzo was rebuilt as well, and Witt found his way into the lead more than once (though he didn’t necessarily win, he was typically “in the money”). Eking 325 miles per hour out of 485 hp, Bonzo was faster than the fastest U.S. military fighter planes of the day.

An Airplane Built for Two

Backing up for a minute, one other thing happened in the busy 1936-37 year: Witt took time to design and build another airplane, something with two seats that he dubbed Buttercup. It was supposed to be a quick little machine that could fly support for the race planes. Turns out, with that patented landing gear from Chief Oshkosh and side-by-side seating for two, it was a comfortable 150-mph airplane that was forgiving to land, courtesy of an innovative leading-edge slat and flap system, and it frankly outflew anything in its class.

The Fairchild Aircraft Company expressed interest in a four-seat configuration and Wittman obliged, conceptualizing The Big X, with a 130-hp Franklin engine, but the war intervened, and Fairchild had to abandon the project. (Buttercup did fly support for the Wittman air race team for years and was painstakingly restored in 1980 by Forrest Loveley.)

Acquiring Partners

WW-II put a temporary end to air racing. Wittman went to work teaching Army Air pilot-recruits basic flying with a young man named Bill Brennand, who had grown up sweeping the hangar floors and learning about building race airplanes in Wittman’s shop at the airfield. It was a relationship that would endure. Speaking of which, he also married Dorothy Rady, who ran the school and the FBO while Witt flew. She learned to fly, too, and flew those support aircraft to races all over the U.S.

Post WW-II

When racing started up again after the war, Wittman invited the jockey-sized Brennand to fly the reincarnation of Chief Oshkosh, called Buster, in a new midget racer class, starting in 1947. Fitted with a Continental C-85 engine and its new pilot, Buster won, and won, and won. Finally retired in 1954, the airplane now hangs in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Wittman, in the meantime, was flying a hand-built speedster named Little Bonzo, which tipped the scales at a diminutive 508 pounds empty. This airplane, in numerous configurations and with countless engines (because, come on, the guy was a homebuilder), won races from 1949 straight through 1973, the last Goodyear race. But get this, in 1978 Witt decided to race a little more, so he dusted off the fuselage (and you can bet added a couple tweaks) and went back at it. It wasn’t until 1987 that Witt returned Little Bonzo to its original configuration, with that Continental C-85 engine, and donated it to EAA for its Air Racing Gallery in the museum.

On a Flying Carpet

As for his two-seaters? Buttercup, of which Witt once said, “It’s the only aircraft I ever built that was a little faster than I thought it would be,” evolved into The Flying Carpet, aka The Wittman Tailwind. The Tailwind was a breakthrough: the first airplane to be certified amateur-built under the new CAR 174-3 rule in 1953.

Wittman had joined up with a young builder named Paul Poberezny from Hales Corners, Wisconsin, who wrote a newsletter called “The Experimenter.” Poberezny’s new Experimental Aircraft Association lobbied the CAA hard for an amateur-built aircraft category that would, for the first time in years, legalize aircraft that were built outside of the factory setting.

Poberezny wrote in “The Experimenter” in 1953 that “it is a stepping stone for homebuilders and will encourage an increasing number of individuals to design and build two- and four-place aircraft.” The two men continued their friendship, and when EAA was looking for a larger venue for its annual get-together, Witt suggested the Winnebago County Airport in Oshkosh. (Well, you know the story from there.)

The Tailwind is a fast, efficient, high-wing, braced-cabin monoplane with a traditional tailwheel. The fuselage is steel tubing, while its wood-rib wings are covered in fabric. It turned heads at EAA gatherings for years as Witt refined it, adding more fuel, more power, and eventually, by version W-9L, a nosewheel. An April 1954 “Experimenter” noted that Witt was averaging five gallons-per-hour fuel burn at a 154.6 mph average airspeed. At a time when automobiles barely managed 10 miles per gallon, that kind of efficiency was unheard of, and people wanted in on the game. Witt finally acquiesced and hired an engineer to draw up plans for the Tailwind, but with one caveat. He chose a NACA wing for the plansbuilt design. Turns out that unlike its docile predecessor, Buttercup, this prototype (for lack of a better word, most of Witt’s airplanes were perpetual prototypes) hid nasty stall characteristics, he later admitted, and he wasn’t confident it was meant for the general pilot public to fly.

Builders scooped up the plans in the 1960s, many making their own modifications (there was even a retractable gear version) and ultimately Witt flew one with an Oldsmobile V-8 engine until the airframe itself started to wear out.

He never did get around to having plans for his and Dorothy’s beloved Buttercup drawn up; however, EAA member Earl Luce of Brockport, New York, reverse-engineered one. In 2003 his LuceAir, Inc. began selling plans for the airplane, which stalls at less than 40 mph and tops out at 150 mph on 85 hp.

Plans for both airplanes are available today from Aircraft Spruce & Specialty.

Wittman was great about talking to builders, offering his expertise during countless EAA conventions, even as he continued flying air races and aerobatic shows long after he retired from his position as manager of Winnebago County Airport, now Wittman Regional Airport. He remained a vibrant participant in the organization and was a key participant in helping the EAA Museum find its home adjacent to the airfield.

Steve Wittman surrounded by the people he once employed at Wittman Flying Service, the FBO he founded at the airfield that now bears his name

The Last Ships

Though his racers and ubiquitous Tailwind (of which there are hundreds of successful builds today) were best known, he never did rest well on his laurels. In the last 20 years of his life, Wittman worked on several projects, building and flying the Witt-V, a single-seat midwing monoplane powered by a 96-cubic-inch converted Volkswagen engine, for Formula V air racing, for which many consider him one of the founding fathers. He piloted the aircraft to several air race victories right up through 1989. Plans for the machine, as well as roughly 10 copies in various states of airworthiness exist today.

In the two-place arena Witt continued to expand on the Tailwind mode, creating the O & O Special as he turned 80 years old. The machine, which first flew in 1986, was designed to weigh less than 1100 pounds empty and top out at 180 mph. Being a true cross-country airplane, Witt wanted a 1200-mile range from the bird, and he got close with a Continental O-470J engine and 50 gallons of fuel onboard. He and his wife Dorothy, and, after her death, his second wife Paula, commuted between his home in Wisconsin and a winter retreat at Leeward Air Ranch, Florida, with the airplane.

It was on that commute in 1995 that the Wittmans went missing. Friends and rescuers searched for days, finally discovering the remains of the aircraft and its occupants strewn across a couple of miles of Alabama hills. An NTSB investigation determined that the fabric on the O & O’s wing delaminated and the aircraft came apart in the ensuing dive.

The world of light aviation was stunned speechless by the loss of Sylvester “Steve” Wittman and his wife Paula. There was tribute after tribute to his life in Florida and in Wisconsin, but really the healing took years. His legacy is honored in Halls of Fame and museum pieces, in the rows of Wittman Tailwinds that return to now Wittman Regional Airport each year for EAA’s AirVenture gathering, in the shadows of a homebuilder’s workshop where someone fabricates the innovative slats that makes a Buttercup such a fine STOL airplane, and in what most likely would’ve made Witt the happiest: the Oshkosh AirVenture Cup cross-country race, culminating in those wonderful race planes, individuals, every one, screaming by the flight line in a burst of light and sound and speed.

Special thanks to Jim Cunningham for his generous help with this article.