The Sport Pilot and Light Sport Aircraft (LSA) regulations are by no means a perfect set of rules. But truth be known, the rules could be a lot worse than they ended up being. In fact, some of the ideas are downright brilliant and are being considered for other areas of the FAA’s vast regulatory multiplex. Two areas getting a lot of press lately are consensus standards for aircraft and the driver’s license medical.

There are so few examiners in the gyroplane world that many gyro pilots first become fixed-wing pilots and then quickly transition to what they really want to fly.

Manufacturers of larger general aviation (GA) aircraft are interested in the consensus standards rules designed for LSA because the rules reduce the cost of getting aircraft and associated products certified. The process for getting both simple and complex products certified in the standard category aircraft world is based on rules and systems cobbled together shortly after WW-II. The LSA manufacturing community, along with the FAA, has shown that there is in fact a more streamlined way to do business that reduces costs and brings new products to market safely, and more economically and quickly, than the old-school FAA way. By producing industry-accepted consensus standards and making manufacturers responsible for adhering to those standards, things are working out well.

As pilots get older, one of the dreaded fears is losing their medical. In the Sport Pilot world, where aircraft are slower, lighter and less complex, the FAA introduced the concept of the driver’s license medical. The idea is that if the state believes you are medically fit to drive a two-ton wheeled vehicle at high speed, in close formation on interstate highways, and through highly congested cities while loaded with family, friends and strangers, then you are also OK to fly an LSA with one passenger. That seems reasonable.

In fact it has turned out to be quite reasonable. Since the Sport Pilot rules became active in 2004 through 2011, there have been no accidents in those aircraft attributable to a pilot medical deficiency. That not only shows the wisdom of the driver’s license medical, it has also motivated the EAA and the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (who were in turn motivated by their members, I suspect) to submit a request for an exemption to the regulation requiring Private Pilots to hold a third-class medical in order to exercise their Private Pilot privileges (§61.23).

But there is yet another great thing about the Sport Pilot rules that is head and shoulders above the Private Pilot rules, which is the ability to move from category to category of aircraft without having to re-cover unnecessary training ground.

Acknowledging the Sport in Sport Pilots

One of the things I have observed in the ultralight and Light Sport world is that pilots of lighter aircraft seem far more adventurous than their GA counterparts. While many “real” pilots seem to balk at the idea of flying anything other than a relatively substantial airplane, ultralight and Sport Pilots often fly more than one kind of aircraft. The opportunities for adventure include airplanes, trikes, skydiving, hang gliders, paragliders, powered paragliders, powered parachutes, hot air balloons, gyroplanes and a variety of other aircraft. Oftentimes a pilot will start flying one kind of aircraft and migrate to another either for a change of pace, a change of mission (transportation versus low and slow) or just for the additional challenge.

As it turns out, ultralight flying offers the greatest flexibility for lateral migration among different aircraft categories. There aren’t any FAA training requirements at all for ultralights, so pilots need only get the level of training that they believe is appropriate. That doesn’t always work out because often pilots approach light aircraft with a lack of understanding, either because they already fly more complex aircraft or because they know nothing about aviation except that ultralights don’t require training. That lack of understanding results in a lack of flight training, which can ultimately lead to bad times, an ambulance ride and a price tag far higher than any flight training might have been.

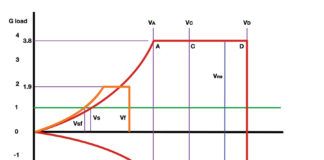

The Sport Pilot rule struck a great balance between safety and required training for people transitioning aircraft categories. For example, if you are a Private Pilot transitioning from airplanes to a Private rating in rotorcraft, you have a lot of dual training and solo flying requirements to meet, which can make the price of transitioning to a new aircraft expensive. Contrast that with the Sport Pilot rule, which really has no additional regulatory minimums for transitioning to other aircraft.

Instead, the Sport Pilot rules place the responsibility for determining how much training is needed not on the pilot (who may not be objective) nor on the regulations (which is a bit too one size fits all), but on the flight instructors who are providing the training. The way that it works is that there is a check and a double-check because two flight instructors are involved in the process. The first provides the transition training. When the first instructor is satisfied that the student is competent in flying the new category of aircraft and can pass a proficiency test, he recommends the student for that test. The student then visits a second instructor to take the test and receive the endorsement to fly the new aircraft.

The system is elegant because it doesn’t require the student to take any extra steps for bureaucracy’s sake. No additional ground school, no knowledge test and no minimum hours. Making it even better, the student doesn’t have to visit a Designated Pilot Examiner (DPE) to get the new endorsement. A properly rated (and easier to find) Certified Flight Instructor (CFI) will do just fine. That places some additional responsibility on the CFIs, but that is a good place for the responsibility to be.

Assessing Where You Are

The first thing you want to do when considering a new challenge is to assess what you are already flying. This discussion is geared toward transitions, but I would like to point out some strategies for aspiring pilots as well as pure ultralight pilots. I get a lot of calls from both groups. Sometimes the aspiring pilots have been student pilots in the past and have completed a large chunk of training and quit for one reason or another.

If you are brand spanking new to aviation, you have a clean slate to work with. The strategy for you is to simply determine what it is you want to fly. What you want to fly depends on a variety of factors that are beyond the scope of this article, but which are important to consider. The good news is that once you have obtained a rating in any category of aircraft, your second aircraft rating will be much easier to get. Still, for the sake of time and money, it is best to learn to fly the kind of aircraft you know you will want to fly for a couple of years. That may mean trying out a few different aircraft and instructors, but it is well worth the investment to go on a tasting tour before you commit to a specific aircraft or training program.

If you have already invested a lot of time and money into a rating and are thinking about moving to another aircraft category, give serious consideration to first finishing the rating you are working on. While all flight training has applicability to other categories of aircraft, the FAA doesn’t value it much unless you complete the training and get the rating. So if you are close to finishing your airplane Private Pilot rating and decide that powered parachutes or gyroplanes are really what you want to fly, your training expenses for your true love may be a lot less if you follow through on your initial training and get that airplane rating first.

If you are an accomplished ultralight pilot, the advice is actually the opposite. If you already fly trikes, powered parachutes, ultralight airplanes or whatever, realize that your time in those aircraft really doesn’t apply to a rating anymore. That being the case, you will have to go through all of the requirements that a non-pilot would to get the rating. That can be both frustrating and wasteful if you are already a competent aircraft operator. Consider learning something completely different.

If you are a powered parachute or powered paraglider pilot, learn to fly airplanes. Ultralight trike pilot? Take up gyroplanes. The idea is to make that FAA-mandated training time count for something instead of going over ground you are already familiar with. After you have earned your first rating, it will be easy to transition back to your first love. The risk you take is that you may find a second love!

And what if you are already a Private Pilot with a single-engine land rating? For you, the Sport Pilot world is your oyster! First off, if you want to fly one of the brand new LSAs, you don’t have to do anything regulation-wise unless you haven’t been flying for a while and need your biennial flight review. Of course, it also makes sense to get checked out in your new airplane, even though your insurance company may be more concerned about that than the FAA is.

Life is also good for those with any kind of rating who want to change to a new category of aircraft. Remember, all you have to do is get trained up to checkride standards by one CFI and get the proficiency check from another CFI. The only common-sense caveat is that both of those CFIs need to be CFIs for the aircraft you want to fly and are training for. That is not always common. For example, finding two powered parachute, weight-shift control trike, or gyroplane instructors within 100 miles of each other can be a challenge.

Determining Your Kind of Flying

It is important, though not critical, to think about what kind of flying you want to do in your new aircraft category. That’s where the limitations of Sport Pilot may kick in. If you enjoy flying at night, Sport Pilot is not for you. If the only airplane rental at the local airport is a Cessna 172, you can’t fly that with a Sport Pilot license either. That doesn’t mean a Sport Pilot rating can’t be a steppingstone to a Private rating. However, you should make sure that your CFI is authorized to train at the Private Pilot level. If the CFI is, then your training time will count not just for your Sport Pilot rating, but also for your Private rating should you choose to pursue it. The good news is that if you are already a pilot, you will already have a good idea about what kind of flying you want to do.

Do you want to keep up with your friends on their cross-county trips? Transitioning to an LSA offers all of the modern conveniences and a speed increase over the other categories.

Your Opportunities

The biggest decision to make is what to fly. The sport aircraft world actually offers a wider variety than general aviation. The other side of that coin is that training can be a little more difficult to obtain. Be ready to travel depending on what it is you want to transition to. Unlike single-engine airplane CFIs, other training specialties can be rare, with many of them numbering less than 100 nationwide. Combine that with conflicting work schedules (not just yours; most sport CFIs have a day job), seasons, weather and equipment availability, and you may have a challenge ahead of you.

That makes the tasting tour even more important. Try to research your new aircraft as carefully as you can before you commit to training or—heaven forbid— an aircraft purchase. Most CFIs offer introductory training flights and those can be very instructional indeed. You may learn that the new aircraft is everything you ever wanted out of aviation, or you may find that it really isn’t your cup of tea. Either way, the price is well worth it.

Spread Another Set of Wings

Ultimately, taking on the challenge of earning a rating in another category of aircraft turns you from an elite, one out of 600 kind of person to something like a one out of 80,000 kind of person in the U.S. You are already special (your mom explained that to you years ago), but you can become even more special by learning to fly something many people don’t even know exists.