Flight-testing Experimental aircraft remains a hot topic among homebuilders-and for good reason. First flights of any new aircraft, whether factory-built or made from a kit or with only a set of plans, are always exciting, at least to the crowd that gathers to watch. Witness the thousands who viewed the first hop of Boeings new 787 Dreamliner. Among Experimental/Amateur-Built (EAB) aircraft, first flights are risky enough to raise some hull insurance rates or possibly eliminate the availability of insurance entirely for the first few hours.

Because Experimental aircraft-even from well-established kit companies-are considered unique (as in one of a kind), the person at the controls is literally an experimental test pilot. Attempting to reduce the casualty statistics, FAA offers its 77-page Advisory Circular 90-89A on how to plan and conduct homebuilt aircraft testing, and the EAA has its flight advisor program that enlists experienced pilots to help new homebuilt owners make wise decisions.

Flight advisors (whose services are free) are prohibited by the EAA from testing the clients new plane and from making the decisions. As stated in AC 90-89A, the objective is to expose the new homebuilt owner to rational decision making such as who should test the new plane, where to do it and, to some extent, how the tests should be conducted. Recent flight proficiency in something similar to the new homebuilt and testing from an appropriate airport are among the first topics discussed.

Flight-Test Durations

The designated airworthiness representative (DAR) who inspects the paperwork and officially turns the collection of parts into an aircraft determines the test area and the duration of solo-only flights during what is known as Phase I. Traditionally, Experimental-category testing consists of 40 hours within the test area unless the engine/propeller combination is certified on some type-certified airplane such as a Piper or Cessna. In that case, it is usually 25 hours.

Now, however, there is a new category of Experimental aircraft that results in a test program much different from the Experimental/Amateur-Built standard. Experimental Light Sport Aircraft (ELSAs) are based on a factory-built special category LSA that has been approved by the FAA to meet the ASTM consensus standards and definitions of LSAs (120-knot maximum level speed, 1320-pound gross weight and others). Unlike EABs, which can be modified as desired by the builder, an ELSA must be identical to its prototype SLSA, and the factory may finish the ELSA kit to any level. The amateur-built (major-portion or 51%) rule does not apply.

The result is an ELSA essentially like its SLSA predecessor. And the prototype SLSA must have undergone extensive flight tests to meet ASTM consensus standards. Thus first flights of an ELSA are much more the equivalent of

production tests rather than experimental tests. Unlike EAB testing, where kit factories seldom require specific tests during Phase I, the ELSA kit factory must prescribe customer flight tests in detail. SLSA flight tests, done by a professional test pilot, include elements that non-professional test pilots should avoid such as spin and flutter evaluations. This means these tests need not be performed by an ELSA production-type test pilot. The bottom line: Airworthiness inspectors are requiring Phase I testing to complete factory ELSA test requirements with as little as 5 flight hours (compared with 25 or 40 hours for EABs).

Taking My Own Advice

First, an unsolicited comment: My long-held opinion is that every kit marketed as an EAB should come with a statement that the prototype (admittedly not necessarily identical to the kitbuilt version) has been tested to a particular flutter-free dive speed and spin-tested in specified conditions. Kit buyers should demand these details before writing large checks.

I recently completed a Vans Aircraft ELSA RV-12, one of the first finished. Studying the EAA flight advisor materials, I seriously considered asking someone from the Vans factory to make the first flight or two. But after flying the red factory prototype last May, first-flight qualms disappeared. I experienced the feel (light, but solid and stable), the numbers (75-knot initial climb speed with half flaps and 52-knot full-flap approach) and touchdown attitude (nose well above the horizon for a slow, soft arrival). These were all key points I would want to understand for my own RV-12s first flight.

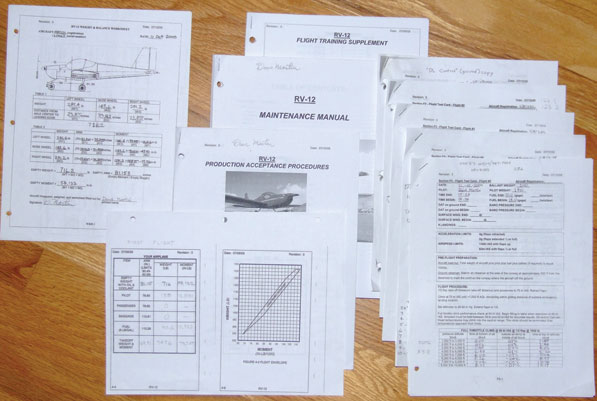

Discussing initial flights with many EAB pilots gives the impression that few are assigning themselves systematic, written-down, envelope-expansion tasks during the lengthy Phase I period. Contrasting this is the five-flight test program specified in the Vans RV-12 Production Acceptance Procedures Manual. This document contains ground checks and adjustments of all the important systems: flight controls, seat restraints, the engine including carburetor balancing, the fuel system for leaks and adequate delivery and calibration of the float-type fuel sensor, pitot and static system leaks, and weight and balance.

Test cards for each of the five flights consist of three to four full-size pages of test items. Test Flight No. 1 includes 73 airborne checks. Planning to stay within gliding range of the runway, I engaged a small group that could help me complete all Flight No. 1 items in a reasonable time. The plan was to equip a ground crew with handheld radios, a clipboarded copy of the test plan, and a radio plan to use a discrete training frequency once I was above the traffic pattern.

Among the many ASTM ELSA-required documents are detailed test-flight cards (right).

Working the Plan

Each test card required noting barometric pressure, outside air temperature (OAT) before and during the flight, fuel quantity before and after, and wind conditions. Test Flight No. 1 called for light loading (14 gallons of fuel and me), takeoff with the standard half-flap setting, climbing at Vy (75 knots indicated) to 3000 feet, and setting a reasonable slow cruise rpm. The only surprise on the initial climb was the need for down stabilator trim, and I reset the index mark for subsequent flights.

Everything looked, felt and sounded normal. Leveling off above pattern altitude, I switched to the tactical frequency and began relaying lots of data to the ground. I wrote down a few numbers on my copy of the card, but I mostly relied on the radio link. In less than 35 minutes we had covered all of the initial data, and I set up for a larger-than-usual pattern. Knowing that Id need to work at getting down to approach speed, I slowed to 80 knots and deployed half flaps early on the downwind leg, and came to idle and full flaps abeam the touchdown point.

Everything worked, resulting in a 52- to 55-knot final at idle, a soft touchdown near the numbers and runway exit at the first turnoff, after about 700 feet of roll. Beginners luck. All 73 card items were finished in 38 flight minutes.

The next four test flights (2 through 5) required climbing to 10,000 feet in several conditions (Vx and Vy, flaps up and half down). I attempted to report OAT at each 1000-foot level, but on the first climb I realized when getting to 4000 feet that Id forgotten to push the mic button while reporting. It was back down to start over.

Flights after the first one required putting 100 pounds of ballast in the right seat, which was the most difficult part of the program-accomplished with double plastic-bagged sand set in a box strapped to the seat.

Summary Judgment

All of this worked to complete the five flights at close to the 5-hour test minimum. Reports included 1 G and accelerated stalls and stall-warning checks in all configurations and several loadings, indicated and true airspeeds at various altitudes, power settings and configurations, trim effects, controls effectiveness (little or no rudder was needed for banks at a 100-knot economy cruise airspeed) and fuel consumption. Phase I was finished. As I write this, 15 passengers have experienced the airplane, and they all like it.

So far, the Vans RV-12 is the only ELSA kit available in quantity, but these test techniques can and probably should be used by EAB test pilots of LSA-qualifying airplanes and also the faster, heavier variety of homebuilts. This stuff is useful, fun and beats floating around the sky waiting for the hands on the clock to move.

![]()

Dave Martin served as editor of this magazine for 17 years and began aviation journalism evaluating ultralights in the early 80s. A former CFI (airplanes, gliders, instruments), hes flown more than 160 aircraft types plus 60 ultralights (including a single-seat, no-basket hot air balloon). Now living at a residential airpark in Oregon, he flies his new Vans Aircraft RV-12.