Having a control cable fall out of a pulley groove in your aircraft is not normally on the list of things to worry about. With proper cable tension, the likelihood of a problem with cable derailment is just not on the radar.

However, when the tension of a cable is relaxed, it is not uncommon to find the cable popping out of the pulley groove. Correcting this condition usually requires help by hand to set it back in place.

So when is the tension of a cable ever relaxed? The most common time to encounter a relaxed cable is when you are relaxing in your hangar performing maintenance or a condition inspection on your aircraft. Let’s say your homebuilt design uses a cable to operate the elevator. The cable will become loose when you disconnect the cable shackle from the elevator. (You might be checking for free movement of the elevator—looking for that noise).

While the cable is disconnected, depending on gravity and the position of the pulley, there is a good chance that the cable will fall out of its groove. Not a big deal to reposition the cable back in—but the trick is to have access to those pulleys. If the pulleys are out in the open, there’s no problem. But if they are buried in an enclosed space, you may be confronted with many fasteners and access panels before finishing your job. In some cases, you may need three or four hands to guide that cable back in place while hooking up the ends. I have seen aircraft designs where rivets were required to be removed to gain full access to cable pulleys.

Fortunately, there’s a simple solution—the pulley guard. This device can take several forms, but the principle is the same: Trap the cable so that it cannot move to a position outside of the pulley groove. This is a component you need to make yourself; don’t look to find one at a store.

Cut some scrap aluminum sheet (about .025 inch or .032 inch thick is just fine) into approximately half-inch strips slightly longer than the diameter of the pulley. After marking the center of the length, find an object about the thickness of the pulley width to use as a form for bending this strip around. (I found a piece of plywood that was just right). The center you marked on the strip is used to center the two bends around the form.

The last step is to drill two holes at each end of the strip that will fit under the pulley’s axle bolt and nut. Take some care before marking and drilling. We want the position of the guard’s gap to not touch the pulley edge, but not be so far away that the cable can escape the groove. Take your time holding the guard in this “just right” position and mark the two holes for the bolt on each side.

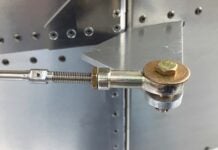

The pulley’s axle bolt and nut are tightened down, securely trapping the guard underneath. We don’t want the guard rotating and causing unforeseen problems. If you are worried about movement of the guard, a rivet placed through the guard and bracket can address that concern.

An alternate method for keeping the cable in the groove is to use cotter pins and a quarter-circle metal corner on each side of the pulley (see photo below). These cotter pins act as cable guards and are placed at just the right distance from the edge of the groove. If a cable wraps around the pulley at a sharp angle, more than one guard is needed (or multiple cotter pins). Note the series of holes at the perimeter. This design provides a universal fit. The location of the cotter pins is based on the angle that the cable wraps around the pulley.

Alternate guard style using cotter pins. Because this pulley is removable for a wing folding feature on a RANS aircraft, the guard keeps the cable with the pulley when it is slack.

For a minimal amount of effort invested in fabricating guards for your most vulnerable pulleys, you will be relieved of time-consuming frustrations for years to come during maintenance operations on your homebuilt.

![]()

As the founder of HomebuiltHELP.com, Jon Croke has produced instructional videos for Experimental aircraft builders for over 10 years. He has built (and helped others build) over a dozen kit aircraft of all makes and models. Jon is a private pilot and currently owns and flies a Zenith Cruzer.