Here’s an aviation trivia challenge: What is an RLU-1? Here’s a hint: It won the Most Unusual Instrument Panel and Most Popular Homebuilt awards at EAA Rockford 1965. Here’s another: The designation identifies the first airplane Charley Roloff, Bob Liposky, and Carl Unger designed. The last member of this trio, wearing a tie, backwards flat cap, and red waistcoat, gave rides in the prototype at EAA conventions for decades.

That’s right. The RLU-1 is the Breezy.

The prototype retired to the EAA Aviation Museum. This one is the handiwork of Jeff Point. A pilot since 1989, the 45-year-old Milwaukee Police Department captain said building a Breezy “was kind of a whim.”

Still flying the RV-6 he built in the 1990s, he said the building bug bit again. “I wanted something different, something low and slow.” Having recently married and acquired a hangar at East Troy Municipal Airport (57C), the economics of “scratch building really appealed to me.”

An annual pilgrim to EAA Oshkosh since the 1980s, Point watched riders line up for rides in the Breezy with Unger and, after his retirement, Arnie Zimmerman. “I never took a ride on one, but I always thought they were neat, so why the heck not.”

A Breezy is like a motorcycle, said Point, who has ridden them for decades. You don’t ride in either of them—you ride on them. And like a motorcycle, flying a Breezy requires acclimation. Using your toes as a visual reference comes quickly. Adjusting to the pitch changes takes longer.

Flying the Fulcrum

On the ground, a Breezy is “pretty neutral around the axles,” said Point. A force of 30 pounds will put its tail on the ground, “and it is pretty happy to sit there with the nose in the air.” That’s why pilots tie down a Breezy on all four corners.

In profile, it is essentially a steel-tube teeter-totter. The pilot and passenger are ahead of the center of gravity, and the main wheels are behind it. On takeoff, the main gear is the fulcrum, and “when it rotates, the pilot goes from the ground to 6 feet in the air.”

Point’s Breezy “stalls at 41 mph, but on takeoff you can’t rotate the thing at any speed under 45 when solo. With a heavy passenger, it is 55 or 60 mph before you have enough authority on the tail to rotate.” To increase its authority, Point extended the elevator 2 inches. “In hindsight, 3 would have been better.”

The plans show no trim system. “For the life of me, I don’t see how you could fly the airplane without it,” he said. If rigged for trim when solo, the CG change with a heavy passenger would demand “a lot of back pressure.” To avoid this, Point installed electric trim, mounting the servo on the elevator.

Off the ground and flying around the CG, the magnitude of pitch changes calm. Until you do stalls, said Point, who put the Breezy through a comprehensive 40-hour flight test program. They are not violent. “But when you are way out on the nose, even a 5-degree drop feels like the bottom fell out of the elevator. I had to do a dozen before I started to get comfortable with them. I never worked up the courage to spin it, and I don’t know that I ever will.”

Power changes have little influence on pitch because the tail feathers and prop are on the same plane. Weight and balance is another matter, and Point tested the Breezy at its fore and aft CG limits.

“I had 230 pounds of me in the pilot’s seat and 240 pounds of ballast strapped in as far forward as I could get it, and I couldn’t get it to the forward limit,” he said. “I was more worried about the aft limit, really,” and bolting dumbbells to the tail examined it. “It’s a little more sporty, but nothing crazy as far as stall behavior or pitch stability.”

Point included climbs and descents in his CG testing, and plotting the data points revealed VX and VY and best-glide speeds at different weights. “Best glide is 52 mph solo and 56 mph with a passenger, which is convenient because that worked out to be VY.” But Point climbs at 60 mph because it lowers the nose a bit and increases the stall margin.

Breezy Glass

A Breezy’s instrument panel is under the pilot’s legs. Point’s is unique. An MGL Avionics XTreme EFIS replaces VFR steam gauges. “It’s a slick little unit, an entire Cub panel on one screen, and I’ve been really happy with it.”

Easy installation influenced his decision. Engine sensors connect to the brain box mounted just ahead of the O-200; a two-conductor wire connects it to the screen. A lightweight B&C alternator and EarthX lithium battery provide 12 volts.

Data logging was another factor. “It records every single parameter at 1 hertz (Hz), and you can download it to an SD card. It’s really nifty when doing flight testing because writing things down in a Breezy is a challenge. You can concentrate on flying the test profile precisely. Then you dump the downloaded data in an Excel spreadsheet and go to town.”

Under his right leg is an MGL communication radio with intercom, switches and circuit breakers, and auxiliary power ports. “This is an IFR [I follow roads] airplane,” said Point. “There is no GPS, no loran, no transponder, no ADS-B. If I need to find my way somewhere, I’ve got ForeFlight on my iPad mini that I wear on a kneeboard.”

The iPad also found his iPhone after an unbuttoned right cargo shorts pocket led to a drop test from 500 feet. “Apple’s Find My Phone app is the real deal!” said Point. A dot pinpointed the phone in a Mukwonago farm field about 5 miles from the airport. Driving to the field, he walked to the dot. Surrounded by tall grass, he hit “Play a Sound, and I heard a glorious beeping about 15 feet away and found it, no worse for wear.”

Building Little Projects

“Building an airplane is not one big project,” said Point. “It is 10,000 little projects. If you keep completing little projects, sooner or later you’ll have an airplane.” The challenge was working in his two-car detached garage and making room every night for his wife’s car. “My entire workshop was on wheels so I could slide everything to the side when Sally got home from work.”

The satisfaction of completing the nine-year project was its greatest joy, Point said. Second to that was his first Breezy flight, courtesy of Arnie Zimmerman, who “let me fly it for an hour back when I started building mine—it convinced me that this was a project worth finishing.”

Point ordered his plans from Carl Unger in 2008. (His son, Rob, took over when Unger died in 2013 at age 82.) Point described the plans as “pretty sparse; they leave a lot to the imagination.”

Building the prototype, RLU didn’t draw plans because they guessed that few people would want a ride, let alone plans. They never guessed that it would be Rockford’s most popular homebuilt in 1965. So they measured the prototype and drew the plans, said Point, adding, “There are a few dimensions that don’t add up.”

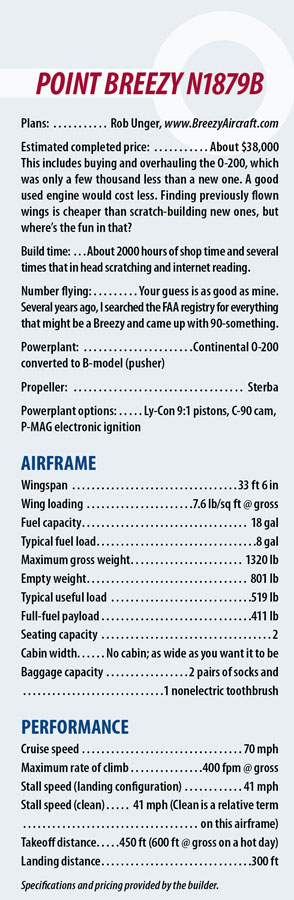

With its wide back seat, the prototype is a tandem three-seater. Point built his seats according to the plans, but with insurance and Light-Sport eligibility in mind, his single-stick Breezy straps in two people.

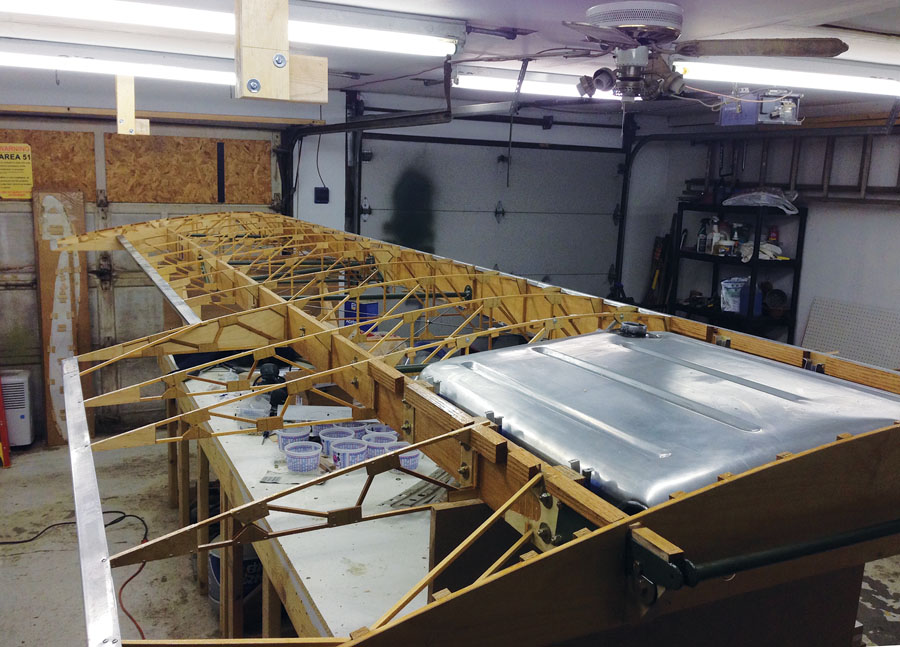

There are no wing drawings because the prototype used rebuilt panels from a Piper PA-12 Super Cruiser. Rather than scrounge, Point went shopping at Wag-Aero, in nearby Lyons, Wisconsin. He bought plans for its Sportsman 2+2, wing spars, some plywood, “and a mile and a half of quarter-inch cap strip.”

Aircraft woodworking will not overly challenge anyone “who’s built a birdhouse in a shop class,” said Point. “It’s a lot of cutting out and sanding sticks so they fit together in a nice pattern.” He used T-88 epoxy to unite the sticks and an old paper cutter to subdivide thin plywood sheets into 2000 1-by-2-inch gussets that reinforce the rib joints.

Besides closely matching the PA-12 wings, the Sportsman plans “filled in a lot of the details on the wing-attach fittings, struts, and tail feathers.” In figuring out the rigging, he “routed the aileron cables up the front strut Vagabond-style and the interconnect behind the rear spar Cub-style.”

A salvaged 18-gallon Decathlon wing tank “was a perfect fit for the Wag wings,” Point said. “I rarely fly with 18 gallons; 8 to 10 gallons is the usual load. With 18 gallons I have 45 minutes of flight time with a 3-hour reserve.”

When it was time to cover the wings, “my friend, neighbor, chapter member, and Kitfox Mark IV builder Bill Stilley talked me into trying” the Stewart System. As for the paint scheme, “I just like the WW-II trainer look,” he said.

“I really liked Stewart for ease of use, from their glue all the way through the top coat,” said Point. “It is a completely different way of thinking. I’m convinced that people who have problems with it didn’t follow the instructions and sprayed it like urethane. Bill and I both took awards home from Oshkosh in 2018 [Plans—Outstanding Workmanship and LSA Honorable Mention], so it must be pretty good stuff.”

Scrounging is a part of every Breezy birth. Point found his unique yoke in a scrap heap. “It’s out of a 1946 Cessna, the only year the company used that pretzel style yoke on the 120 and 140.” He found the Cessna 150 nose gear fork on eBay, “and I got the nosewheel from a guy who started building a Breezy a hundred years ago and abandoned the project.”

The nose gear proved to be the project’s greatest challenge. “With all the heavy welding involved, [the nose fork fitting] gets out of round, so getting the nose gear to fit took some effort,” said Point. A novice welder, he took the EAA SportAir class and attended the gas welding workshop during Oshkosh. After a lot of small-part practice, an FAA-certified welder at the airport analyzed his technique before he started on the Breezy.

Point built the 6.00×6 main wheels and Cleveland brakes from a disparate collection of bits and pieces from different airplanes, “but the patterns match and they all work.” A single left-hand lever controls the master cylinder from a go-kart, and “I can chirp the wheels at 40 mph.”

Ol’ Ironsides Power

Point is a member (and currently president of) EAA 18 in Milwaukee; another member, Ron Scott, was technical counselor on Point’s RV-6. Perhaps best known for his half-century leadership of the EAA convention communication crew, Scott also designed, built, and first flew Ol’ Ironsides, N1879, in 1969. Powered by a Continental O-200, it looked like a 7/8-scale Wittman tailwind. What made it unique was its stressed fiberglass skin construction.

Scott died in November 2015. Ol’ Ironsides made its last flight several years before that, Point said. After 45 years of service, an axle weld broke while rolling out on a grass strip. “The gear leg dug into the turf, and not even Chuck Yeager could have saved it at that point.”

Scott was getting ready to retire his wings, and Point was engine shopping, “so I made him an offer; he sold me Ol’ Ironsides’ engine on the condition that I’d give him a ride when the Breezy was done. Unfortunately, I came up about a year short of delivering on that promise.” As homage, Point registered his Breezy with Ol’ Ironsides’ N1879 appended with a B, for Breezy.

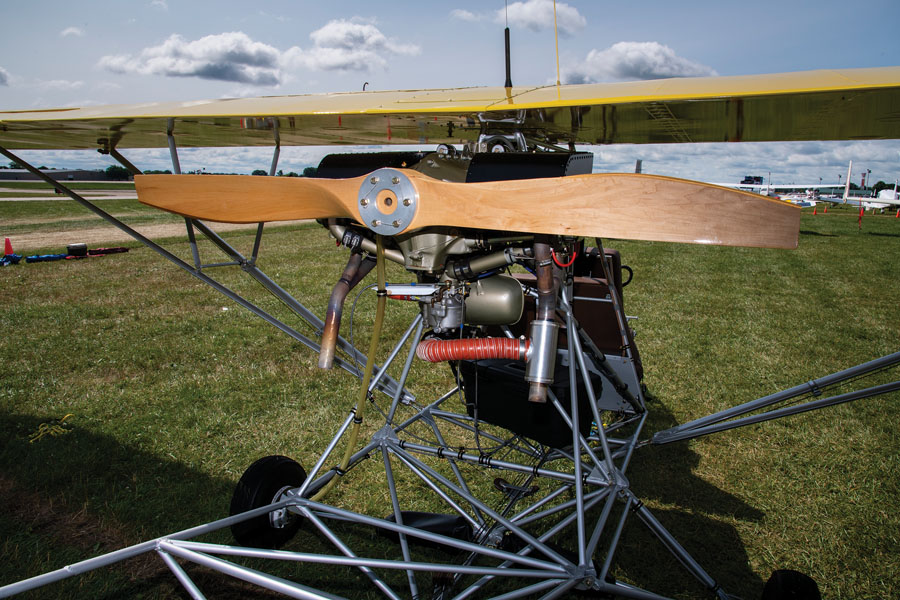

Point dismantled the O-200 and sent the cases to Tulsa, Oklahoma, so DivCo, Inc. could do a prop-strike inspection and make the necessary changes to convert it from a puller to a pusher. For their inspections, all the steel parts went down the street to Aircraft Specialties Services.

Point dismantled the O-200 and sent the cases to Tulsa, Oklahoma, so DivCo, Inc. could do a prop-strike inspection and make the necessary changes to convert it from a puller to a pusher. For their inspections, all the steel parts went down the street to Aircraft Specialties Services.

Point rebuilt the engine with a new-old-stock C-90 camshaft that “all of the experimental Super Cub guys swear by” because it shifts the torque curve to the lower end of the rpm range. With its new 9:1 Ly-Con pistons, “my O-200 might actually make a hundred horsepower.”Seeking redundancy, Point replaced the left Slick 4301 magneto with a P-MAG electronic ignition system. “The Breezy does not lend itself well to power-off landings. It lands nice and slow, but it doesn’t give its riders a whole lot of protection, and I didn’t want to take any unnecessary chances with the reliability of the motor.”

For most of its life, Ol’ Ironsides didn’t have a starter. “But as Scotty (and all of his hand-proppers) got older, we convinced him to add a lightweight starter and battery. He said he should have done this years ago!” Today, a lightweight B&C starter brings the O-200 to life.

Point had to figure out the Breezy’s throttle quadrant and its connections on his own. Ed Sterba carved the prop. “I told him what I was looking for dimension-wise, pitch-wise, rpm-wise, and he nailed it on the first try. Ed makes a nice prop—my RV-6 started with a Sterba prop—and it is exactly what I wanted.”

First Flight

With a goal of flying to AirVenture 2017, Point worked feverishly. “Around April, I found myself pushing, contemplating shortcuts, and I finally said, ‘That’s It! I’m not taking the airplane to Oshkosh this year.’ It was the best thing I ever did. It took all the pressure off, and I was able to do things in a more deliberate manner.”

The Breezy passed its FAA inspection on August 5, 2017. Before making its inaugural flight, Point traveled to Bult Field (C56), “the Breezy capital of the world,” for some stick-and-rudder preparation. “I’d flown a Breezy before, but not recently,” Point explained. Mike Fisher has a two-stick Breezy, “and I wanted to get comfortable before I flew mine for the first time.”

Before his first flight on August 26, 2017, Point strapped 120 pounds of ballast in the back seat to center the CG in its envelope. Then he strapped on a helmet and parachute, which he wore for flight testing. Since then, he dresses for the weather. Wind chill is a preflight consideration, he said. Dressing in layers helps, but 60 F is his threshold for flight.

If there was a surprise in building a Breezy, it was sharing it with his wife. “Sally likes to ride motorcycles and all that stuff,” Point said. She doesn’t share his airborne passion, “but she really enjoys the Breezy, and we fly together after work on warm days.”

I had a very nice Breezy from 1982 to 1985. The first time I flew it solo was to bring it home from another airport a couple of hours away. When I broke ground, the nose wanted to go straight up, even with full down elevator trim. After getting home with the sorest, stiff arms you can imagine, I found out the minimum weight for the pilot for CG purposes was 190 lbs – I weighed 150! No wonder it wanted to climb uncontrollably! After strapping a 40 lb steel “torpedo” to the keel everything got better.

I do have some actual IFR time in it – another story for another time!

I still miss it.

Best – David Howe

Back in about 1975, a Breezy flew into Casa Grande, Arizona where I was skydiving. It was such a cool machine, and one of our more experienced jumpers talked the pilot into taking him up to 3,000 ft, where he set up for the jump. Everything went great, except for when Scotty stood on the right main gear (which the pilot had neglected to use the brakes on), and Scotty went spinning off. But all ended well, and Scotty was probably one of the very first Breezy jumpers back in the day.

Great article as usual Louise. I need to ask, beg wheedle, cajole Jeff for a ride if I can muster up the courage…a lot different than my RV-7 or RV-1…

Jerry Fischer