The year was 1961. The handsome young man from Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin, loaded his wife and son into the family’s ’57 Studebaker and headed south toward Rockford, Illinois. None of them knew the pleasant 140-mile drive was the start of a lifetime journey.

Arden Hjelle (“jell-e”) loved anything mechanical. For a kid in post-WW-II America, mechanical talent meant cars—first a Buick roadster, then a Packard, a Lincoln, a Porsche, and a Cord. All were well-worn, of course, but that didn’t matter; the fun was in fixing them and making them run. Arden landed a job as an apprentice machinist at the local auto parts store while still in high school, and married his sweetheart, Jean, two weeks after her graduation. Life was good.

Getting drafted and sent to Korea didn’t slow him down. In a fit of common sense, the Army stationed him in a motor pool, repairing the machines of war. Always restless, he spent his off-duty time building a motorcycle from scrap, and most of a tiny straight-six engine the size of a cigarette pack. Eventually his enlistment ended, and when he came home, his old job as a skilled machinist was waiting for him.

Learning to Fly

Hjelle settled into a comfortable life, in a house by Lake Winnebago. Jean insisted there be no more cars around than fit in the garage, so Arden built a four-bay shop building larger than the house. When cars grew stale, he built a cabin cruiser, just the thing for a family with a lake in the backyard. And, of course, he grew fascinated with airplanes. The GI bill paid for flying lessons in the light planes of the day, mostly Champs, J-3s, and C-140s. Hjelle steadily built the hours necessary for a commercial ticket, renting and borrowing like any new pilot.

It was impossible for a young flyer from Fond du Lac to not know of Winnebago County’s most famous aviator, air racer Steve Wittman. Wittman’s base was at Oshkosh, only 15 miles to the north, where he managed the airport and ran his Wittman Flying Service. In August of 1956, Wittman hosted the first Professional Race Pilots Association (PRPA) race to be held at Oshkosh, a three-day event which no doubt attracted local pilots like bugs to a light. The total crowd was estimated at 100,000 people; on Saturday, they so overwhelmed the organizers (an Oshkosh civic group) that the CAA representative threatened to shut down the whole show. Wittman won the final by 3/10s of a second after 12 laps around a 21/2-mile course, collecting a grand total of $850 in prize money.

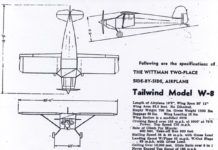

No one was surprised when Hjelle began to think about building an airplane. Wittman’s 1953 Tailwind design was the obvious frontrunner, but there were a limited number of other two-place designs, and then, as now, the EAA Convention was the place to see them. The birth of a son may have slightly delayed the process, but by 1961 three-year-old Tim was deemed grown enough for the fly-in camping trip.

The 1961 EAA Convention was the ninth for the growing association, the third year at Rockford IL, and first scheduled for a full five days. Visitors found about 85 fixed-wing homebuilts in the showplane area, with the Tailwind (12), the Corbin Baby Ace (11), and the Nesmith Cougar (6) being popular. At 160 hp, Steve Wittman’s personal all-red tricycle gear W-9 was the most powerful homebuilt at the Convention. Like every homebuilder before or since, Hjelle walked the rows, inspecting the designs and measuring them against his favorite. The Cougar made the short list, but in the end he stayed with the Tailwind. That fall, Jean drove up to Oshkosh with little Tim to buy the plans.

Building the Tailwind

The next 31/2 years were a blur of activity. As a skilled engine machinist, Hjelle wasn’t challenged by overhauling a C-90 Continental, or making tapered gear legs from scratch. The tube frame wasn’t complex, the systems were simple, and the designer was close by if there were questions. As it turned out, Steve Wittman had reason for regular visits to Fond du Lac, and he began to stop by the Hjelle place. Nearing 60 and without children of his own, he took an interest in the young man, which quickly grew into a deep mutual friendship.

N117A was completed just prior to the 1965 EAA convention. Wittman did the first flight. Finding time for a 50-hour test period was difficult, as the Hjelle family was occupied with another new arrival; Jean gave birth to a daughter, Sue, less than a week before the show. Nonetheless, Arden and young Tim, now 7, flew the Tailwind to Rockford on schedule.

N117A was mobbed all week, start to finish. The Tailwind was then the most popular design in the homebuilt world (there were 25 at the show), but no one had ever seen a Tailwind quite like this. The cowl was a custom job with ram air, a slot exit, and a built-in landing light. The interior was fully upholstered in a pattern much like Detroit’s latest hot car, the ’65 Mustang. The control surface gaps were perfectly straight, and the doors…well, nobody could believe the doors. It wasn’t possible to slip a business card under an edge anywhere, yet they closed with the solid click of an expensive briefcase. It was, in the eyes of many, a quantum leap in craftsmanship—handcrafted, not homebuilt.

In those early days, many of the aircraft awards were sponsored. Witt-man offered a trophy for “Best Tailwind,” of course. Ditto for the folks from Razorback, the new fiberglass fabric covering. As predicted all week, N117A received both, plus the big cup: the EAA’s sole “Most Outstanding Workmanship” award.

Right Time, Right Plane

Some say all success is a matter of timing. If so, the time was right for Arden Hjelle. The build-your-own-airplane movement was exploding, and now it had a star. In a 1966 Sport Aviation cover photo, he has the look of an All-American, the sort of fellow you wish your daughter had married. By late 1967, Hjelle’s Tailwind had reached Flying magazine, featured (along with a Mustang II, a Smith Miniplane, and Cassutt) in an article which attempted to explain the homebuilt phenomenon to owners of the certified breed. Despite not being a Bonanza, it was described as “…gleaming, glossy, epitome of the art…”

A teenager from Milwaukee, Ronald Wojnar, set his heart on winning the EAA’s 1967 model airplane competition, and was introduced to Hjelle by a family friend. Hjelle, after a bit of conversation, decided the kid was dead serious, and gave him some of 117A’s extra paint and upholstery material, the loan of his Tailwind plans, and the opportunity to photograph every detail. Wojnar proceeded to scratch build an incredibly detailed miniature and win the contest. One of the prizes was his very own set of Tailwind plans, received from Steve Wittman himself. Wojnar went on to Purdue University, became an aeronautical engineer, then served in the Wisconsin Air Guard while working his way to a senior position in the FAA. Today, 48 years later, he still has the plans.

Behind the scenes, Hjelle was becoming a go-to guy for custom machine work, in particular for his friend Wittman, who had proposed an entire new racing class. Formula V racers would be much like Formula I, but limited to VW engines in order to keep costs down. The Hjelle/Wittman engine concept faced the flywheel end forward. A conical-shaped housing enclosed an extension shaft, which in turn drove the prop. Airframe and engine development proceeded through the late ’60s, and both Wittman and Hjelle flew the new V-Witt racer in 1970.

EAA Moves to Oshkosh

The EAA went looking for a new home in late 1969, as the Rockford site had simply become too small. The airport at Oshkosh seemed to have the necessary space, and local leaders thought the convention might become an economic windfall. The Winnebago County Board of Supervisors voted to approve a 15-year contract, including a $25,000 commitment for site improvements in 1970 alone. The money would be needed, as there was nothing on the west side of Wittman Field but farmland.

Technically, 1970 would be the second time the EAA came to Oshkosh. The tiny 1958 meeting had been held in concert with the PRPA air races, but it was such an organizational mess that everyone wanted to forget it. This time would be different. In the 12-year interim, the organization had grown to around 50,000 members, many of whom were willing to volunteer and donate. There wasn’t much time, but work parties were assembled every weekend, and things got done. The sole permanent structure was a steel building erected just north of the tower; everything else would be in surplus army tents. The real focus was a new campground, complete with a paved street grid, electric lighting, and a water well (It’s now the Warbird area).

The 1970 convention was tiny by today’s standards. Except for temporary parking, the entire site was within a rectangle north of Waukau Ave., between Knapp St. and the runway. Opening day found the famous Brown Arch hung over a gap in a snow fence, but nobody cared. Airplane Heaven had found a home.

For the first time, there would be three Grand Champion awards, Homebuilt, Antique, and Warbird. About 280 homebuilts were registered, and those ranks had changed. The rapidly growing homebuilt movement meant the flight line was no longer a collection of Pietenpols, Smith Miniplanes, and homely Stits designs. Now there were new two-place biplanes like the Starduster Too, with their beautiful elliptical wings. The era of the Pitts Special had truly arrived, with no less than 28 in attendance. Three of Bob Bushby’s Mustang IIs and 13 Thorp T-18s heralded a riveting experience for homebuilders. And yes, there were 27 Tailwinds…including N117A.

The World’s Best Homebuilt?

Hjelle had not been resting on his laurels. Whatever little details left undone in the rush to make the ’65 convention had long since been corrected. In addition, the airplane now sported wheelpants, gear leg fairings, and a new metal propeller designed specifically for the C-90/Tailwind combination by Sensenich chief engineer Henry Rose. The fundamental build quality, however, remained the key. When the points were tallied, 117A was again judged the best homebuilt in the world…and the very first Oshkosh Grand Champion.

The years following that first Oshkosh were busy ones for Arden. Professionally, he was much in demand, and ultimately opened his own engine shop in 1978. He was asked to join the nominating committee for the EAA’s Board of Directors in 1979, and served in that position through 1988. He never built another airplane, but he did have one more airplane project in mind.

N117A’s panel is original, right down to the leather key fob, with one exception. The KX175 nav/com wasn’t introduced until sometime in the early ’70s.

In ’73, Steve Wittman rolled out his latest Tailwind, which was then just a bare tube frame. It collected an immediate crowd because hanging inverted on the firewall was an aluminum-block Olds V-8. Hjelle had been working with the aluminum Olds on behalf of auto racing customers, liked it, and got his friend Wittman interested in the idea of converting it to aircraft use. Their goal was simplicity and low cost; it would be direct drive, using a shaft extension much like the Formula V engine, supported by a modified Olds bellhousing.

Wittman first flew the Olds in mid-’74. There were teething problems, but no show-stoppers. Hjelle continued development, increasing displacement to 265 cubic inches. By all accounts, Wittman loved the Olds Tailwind and flew it until shortly before his death in 1995. Today N37SW hangs in the main terminal building at Wittman Field.

Arden Hjelle still lives in the Fond du Lac area. His son Tim continues to operate the family business, Fond du Lac Auto Machine. They still have N117A, and recently Arden’s granddaughter got a few lessons in flying it. Some things are just too good to ever let go.