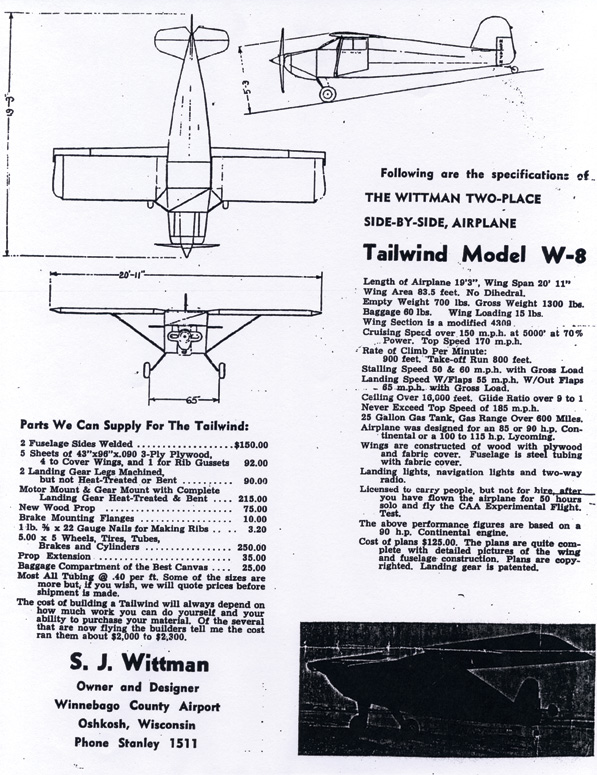

Nature abhors a vacuum, even a small, very specialized one. I know this because I saw it on The Science Channel, but thats not all. In the close-knit group of Wittman Tailwind builders, word of our cover story got out and I was contacted by Jim Stanton. Stanton sells a simply titled three-ring binder full of massively useful information called Building the Wittman Tailwind.

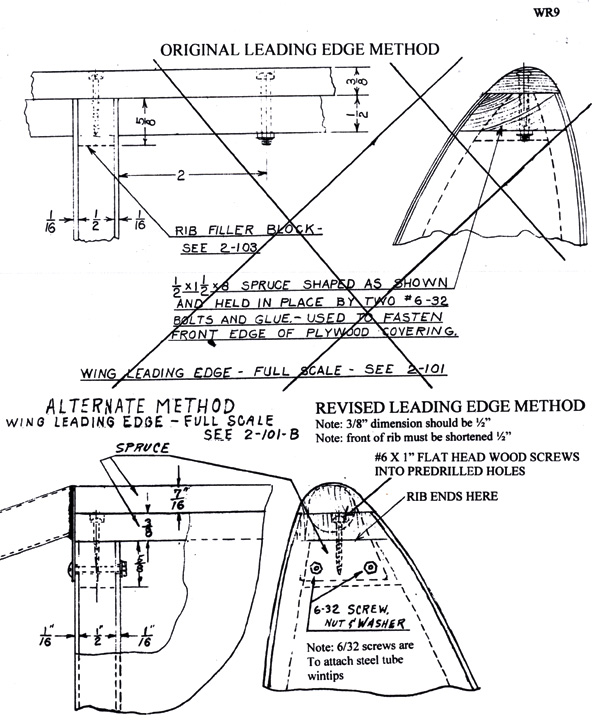

When he emailed, Stanton was careful to note that while the current purveyors of the plans, Aircraft Spruce & Specialty, are doing a fine job supporting the design, plans themselves have some significant errors and discrepancies. He should know. Stanton built a W8 in 1964 thats still flying, and has been involved with the design ever since. According to Stanton, the manual contains collected corrections, hints and tips from the early 1960s, collected by Bud Harwood, and from later builders such as Jim Clement. This format is wonderfully analog in a world of Wikipedia and user groups. (Speaking of which, there is an active group for the Wittman designs, in case you absolutely have to go digital.)

I spent a rainy afternoon appreciating Stanton’s collection of corrections and advice, and it provided some interesting insight into the Tailwind design. For example, something I’d noticed in person while we photographed Jim Rust’s W10 for this month’s cover was a joint in the lift strut near the bottom. Most designers would try to make the strut one piece, as it’s a heavily loaded structural member. But I learned the reason in Stanton’s book. Like many of the novel ideas found on the Wittman aircraft, there were probably several reasons for the stub struts, it says in the manual, describing the steel weldments that emerge from the fuselage side and rise slightly to meet the streamline tubing. Keeping the strut-attach bolt away from the fuselage side does reduce drag. Wittman told me that for the purposes of calculating strut loads in compression, the stub strut is considered part of the fuselage. Thus, the length of the main strut for calculating compression loads is approximately 5 inches shorter than if a more conventional fitting were used. I believe the stub strut more efficiently transfers loads into the fuselage structure than could any type of conventional fitting. It is much easier to weld the stub strut to the fuselage than to weld a heavier fitting.

Ah-ha. So old Steve Wittman knew what he was doing, as if we ever really needed any convincing. With the benefit of Stantons guide, the genius of Wittman’s design is clear. The steel-tube structure appears to be as simple as you can make it, very straightforward. Id originally dismissed Jim Rust’s comment that you could build a Tailwind with a hacksaw and a torch as enthusiastic banter, but now I’m starting to think that while a power bandsaw and a few other modern tools would make your life easier, they aren’t absolutely essential to hewing a Tailwind from the raw.

Seeing the Tailwind from the inside out, so to speak, makes you appreciate why the early days of homebuilding had to be this way. There was no guarantee that the plans creator would be in business long; indeed, offering blueprints often was not in the business plan at all. Early enthusiasts hounded designers like Wittman to offer plans, probably at the threat of just reverse-engineering the thing without the full knowledge of structure, load paths, and aerodynamics, to name just a few of the fiddly requirements. Because commercial kitting was still far off, designs that were popular in the formative days of the Experimental movement had to be buildable by just about anyone with the desire and knowledge of welding, fabric, wood and sheet metal. The number of airframe-specific parts was few.

So much has changed. Today’s homebuilts are full of specialized parts, and not many builders are confident enough in their welding abilities to, say, create new engine mounts out of raw tubing. In the heyday of the Tailwind, that was the only way you did it. I consider all the beautifully machined aluminum pieces in my Sportsman—the CNC-cut members that connect the top of the strut to the internal wing structure, for example-and realize that should any of them need replacement, the only realistic call is to the factory.

Access to this inside information makes me appreciate that plansbuilt designs—at least in this small data set—can be brought to life by those who are not geniuses or artists, just regular guys with a passion for building and the ability to read plans. It also strikes me that plansbuilders have to be inquisitive-why are the tubes angled this way, how have other builders tackled that tube cluster?

I’m both grateful for and envious of those who have the willpower and desire to start (and finish!) an airplane from scratch. Even a small, simple airplane like the Tailwind is a big undertaking, yet it’s an important marker to fully appreciate where we’ve been and how far our sport has evolved.