Wendell and Martha Solesbee have been working for almost two years assembling their Lancair Evolution and are now nearing the end of that process. When we last checked in for the November issue, the Solesbees had hung the mighty Pratt & Whitney PT6A engine and were working through systems installation and integration. That’s no small task, which is why the magazine deadlines caught up with and passed their efforts. (This series did not appear in the December issue, so you didn’t miss anything.)

Of course, part of the delay was due to the nature of the next step: painting and its related preparation. Fortunately, the Solesbees are uniquely qualified to face the challenge of painting. Not only have they built two other award-winning airplanes—a Giles aerobatic plane and a Lancair IV-P—but they also own an automotive paint and body business that restores some 200 cars per month. They and their son, Terry, showed us what it takes to put a first-class paint job on their first-class project.

The Solesbees rented a portable booth to paint the Evolution. It fit well in their hangar at the Chino airport. The booth itself is made of plastic sheeting over a pipe framework. Note the large fan box on the end near the outside.

Since the days of the IV-P, Lancair has made great strides in the quality of its composite work. Where the older Lancair model used hand-laid molds, the Evolution molds are made with computer precision. As a result, there are no more waves and bumps in the fuselage and wings. Parts come out of the mold smooth and straight, and they fit together with much greater precision. It’s probably fair to say that the previous idea of “lock together” parts was true only in the most general sense; most composite aircraft from the 1980s and ’90s needed a lot of finish work to make them look like show winners. Every place where composite sections joined presented new opportunities to refine your smoothing and sanding skills.

Terry Solesbee block-sands and fills the fuselage after the first coat of primer to smooth the high spots left from the manufacturing and assembly processes. He is using a flexible long board to better conform to the continuous curves of the Evolution.

The quality of the Evolution parts saves the builder time and effort when preparing for paint. Here’s an example: The Evolution has a seam where the two halves come together and a recess where the pressure bulkhead bolts through the fuselage. These two areas must be filled and blended into the body. That’s not a lot of work when you consider the size of this airplane.

Other areas that required significant work were the cowl sections, especially the ducts in the lower cowl that couldn’t be incorporated into the mold and had to be hand-fitted. Solesbee says this was the hardest part of the plane to build. Carbon-fiber cloth and epoxy took care of the structural tasks, and a mixture of glass bubbles (often called micro) and resin are used for non-structural filler. Wherever a little extra strength was needed in the filler, flocked cotton fibers (flox) were added to the mix. Because the inlet duct is both large and prominent, the Solesbee’s completed this part of the kit with great care.

Wendell and Terry load the Evolution fuselage into the paint booth. Once the plane is inside, the fan box simply wheels back into place. The dolly that Wendell welded together makes moving the big Evo fuselage easy for two people.

Sand in Your Shoes

Once the cowl was built and fitted, and the seams in the fuselage were blended in, there remained many little things to do.

With any composite structure, pinholes in the skin must be filled. A good high-build primer, properly applied, does the job best. You might think that spraying would be the preferred technique, but actually it is hard to blow primer into a small hole. Small disposable paint rollers work much better, because the rollers press the paint into the holes. The Solesbees used WLS epoxy primer, a product popular with Lancair builders. The primer provided a good material for sanding and blocking, which they tackled next.

Terry puts a second coat of primer on the elevators. Unlike the first coat, which is better applied with a roller, there is no reason not to spray the second coat. Good lighting and ventilation make the booth a pleasant place to work in.

On the curved surfaces that make up most of the Evolution, sanding and blocking is primarily done with a long board using a cross pattern, first 45° to the axis of the curved surface and then 45° in the opposite direction to make a 90° cross pattern. This ensures that no flat spots or low spots will be introduced into the surface by the sanding process. It works well but requires patience for good results. The blocking process reveals low spots that need additional filling, as well as high spots, which must be dealt with carefully to avoid sanding completely through the gelcoat into the carbon-fiber cloth. This process begins with a fairly coarse grit sandpaper such as 80 or 120. The long-board paper comes on rolls with a sticky back, making it easy to use.

With the considerable size of the Evolution it was nice to use two paint guns simultaneously to apply the base white coats. To do this you need two good painters and an air compressor large enough to keep up with two guns.

A lot of testing and mixing went into the color selection process before any paint went on the Evolution. Test strips were painted, allowed to dry, and then checked outside in natural light. Only then could the Solesbees be sure of the colors they would end up with.

Often, when a particularly tough situation presents itself during the blocking process, a guide coat is applied to more clearly reveal the low spots. What’s a guide coat? In this process the surface is sprayed with a thin coat of flat black lacquer and then cross-sanded with a long board. Sanding removes the black paint except in the low spots, clearly identifying areas that need to be filled. Solesbee said that the Evolution was in such good shape that he did not have to use this technique.

Pass the Primer

After blocking and filling until smooth, it is time to apply a second coat of primer. The Solesbees used gray primer, but in retrospect admit they should have used white. White primer would have provided a better base coat for the white paint to follow, making it possible to use fewer coats. If you’re thinking, “Who cares if it takes two or three coats to cover the primed surface?” keep in mind that on a plane the size of the Evolution, an extra coat of paint adds several pounds to the empty weight. As a builder, you’re always looking for ways to save weight, unless doing so impacts safety. Primer and paint aren’t even remotely structural.

Wendell and Terry are all dressed up in their “bunny suits.” As soon as they finish mixing their paints and filling their guns, they will start covering the Evolution with its white base coat.

It’s the nature of composites that after the second coat of primer a few more tiny imperfections surface that must be fixed. If simple sanding won’t cure them, then it might be necessary to fill them with glazing putty. This is only for the smallest imperfections, because it’s essentially just very thick paint. After spotting here and there, these areas need to be primed again to ensure the surface is uniform in color and texture. This second coat of primer is sanded with a dual action (DA) sander or by hand using 400-grit sandpaper. Flat and convex surfaces can be sanded with an air-powered DA sander, but concave (inward curving) surfaces must be sanded by hand because the edges of the sander can cut into them. The 400-grit leaves a smooth surface that still has enough roughness to grip the finish paint.

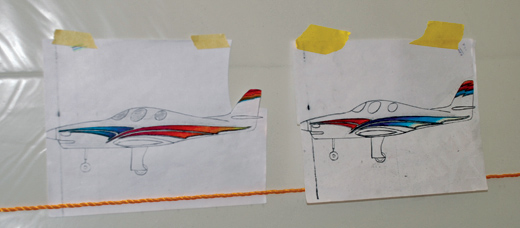

Before the color scheme can be laid out on the airplane, it’s worked out on paper. The Solesbees experimented with many variations before they landed on the final design. Even then, minor changes were made when the actual pattern was masked out.

With masking tape and plastic in place to protect the white base coat, the fuselage is now ready for the first application of color. It will take several times through the masking process to apply all of the various colors.

Covers the World

It is important that the primer and the finish coat paints are compatible. Most finish paints work well with epoxy primers such as the one the Solesbees used, but never assume anything. Always check with the paint manufacturers to be sure all products will work together. A paint job can lift because the finish coat and the base coat don’t like each other—it’s an ugly phenomenon that you never want to see on your own project. This is one place where an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and then some.

The various colors go on one at a time with a smaller paint gun. These water-based paints are much less toxic and require less personal protection than the more hazardous urethane paints. Unfortunately, they also dry much more slowly.

To ensure quality results from their painting project, the Solesbees rented a portable paint booth and set it up inside their hangar. The booth is simply plastic sheeting draped over and fastened to a pipe framework that can easily be set up, torn down and moved from place to place. A large exhaust fan with an even larger filter is installed at one end, and an equally large filter for intake air is built into the other end. The fan box is on wheels so that it can be moved out of the way to push the plane into the booth. This is a slick setup and easily accommodates the large Evolution fuselage without the wings, which must be painted separately.

With the masking removed, Wendell and Terry inspect their handiwork on the tail of the Evolution. Terry will follow up with striping and shadow details later.

Once the plane has been primed with a second coat and sanded, it is time to go over everything with a tack cloth to remove any traces of dust or lint. Tack cloths can be purchased at any good paint supply store. They are cloths impregnated with a sticky or tacky chemical that grabs all the loose dust without leaving any residue.

The White Stuff

Finally, it was time to start spraying those freshly primed and sanded airplane parts. With such a large surface to cover, the Solesbees pressed Terry into service to handle a second paint gun. He also has many years of painting and auto-body experience, and is especially adept at striping and graphics. It’s nice to have a spare expert in the family to make short work of a big project.

Wendell removes the masking from a section of the fuselage. With the slow-drying water-based paints used for the colors, it is important to be patient while unmasking. It would be a shame to rush at this point and have to redo so much hard work.

Terry is pleased with the results as he and Wendell remove the masking tape from the last color application. It is easy for something to go wrong when working with such a complex color scheme.

The Solesbees used Sherwin-Williams Genesis urethane paint for the base white coat. Two double-wet coats went on in quick succession, providing full coverage over the gray primer. “Two double wet coats” is terminology Solesbee uses to describe the application process in which a first coat is applied with a 50% overlap of the spray pattern, followed by a second similar coat applied immediately after the first while it is still wet. The urethane provides a tough and durable base for the color details to come, but it is nasty to work with. It requires special protection for the painter applying it to protect skin and lungs from potentially harmful effects. As with any toxic chemical, careful review of the paint’s material safety data sheet (MSDS) is in order before using it. (See the sidebar, below.)

Sanding, sanding and more sanding. That is what painting is all about. Before the clear coats go on, the entire fuselage is lightly sanded to remove any small imperfections and ensure a good grip for the next layer of paint.

Once dry, the white base coat is sanded with 800 grit in preparation for the color details to follow. This process began with a sketch of what the Solesbees wanted to do. Several schemes were drawn with colored pencils and considered before a final design came together. Next came mixing and spraying a number of colors on a metal sample board to see what they would really look like on the airplane. With all of this finally accomplished, the masking tape went on, tracing the design. The first step was to place green masking tape to the outside edges of the color details. Next, blue 3M Fine Line masking tape was laid up against the edges of the green tape. With the Fine Line tape in place, the green masking tape was then removed. Large areas that were to remain white were covered next until only the areas to be painted with the first color were left exposed. Then it was ready for color.

Color with Universal Appeal

The Solesbees used Planet Color, another Sherwin-Williams product, for the color details. This water-based paint was much different from the urethane base coat—namely in its lengthy drying time. However, Sherwin-Williams highly recommended it for its ability to retain its vivid colors for years. The paint caused some frustration for the Solesbees, but they were pleased in the end. Because there are several colors on their Evolution, the Solesbees put in considerable time and patience to achieve the final results. All of the masking, painting, unmasking, re-masking and painting again is a tedious and painstaking process that is frankly not for the impatient or inexperienced. Terry added a few finishing touches of shadows and stripes to set off the striking design.

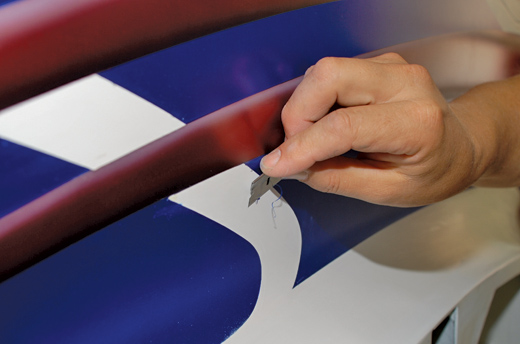

By razor trimming the edges of the color, the clear coat will go on flatter and not build up on the ridges of the accent stripes. This work takes a steady hand and is not recommended for the inexperienced painter.

Before the clear coat was applied, the edges of the colored designs were razor trimmed, another task best done by an experienced and steady hand. Another pass with the tack cloth, and the clear coat went on in two double-wet coats. To really make the finished paint job perfect, the Solesbees took the extra step of carefully block-sanding the clear coat with 400 grit to remove every little wave and imperfection. After that, the clear was hit with 1000 grit and 2000 grit in successive steps. Finally, a good polishing brought a pearl luster to the finish.

Terry has applied shadows and accents with an air brush. These extra touches go almost unnoticed at first glance but upon closer scrutiny really add flair to an already impressive paint job.

You can do it yourself, as the Solesbees did, for a few thousand dollars in materials and a lot of work, or you can pay someone $30,000 or so to do it for you. Most Evolution builders will just write a big check.

The difference between a good paint job and a great one is a lot of extra work. Terry blocks out the clear coat to remove the remaining tiny ripples and imperfections. He will follow with additional sanding using 1000 and 2000 grit. It is critical that he removes only a portion of the clear coat and not disturb the paint below.

If you want to do it yourself, there are some things you will need, starting with a good spray booth. You can rent one or make your own with plastic sheeting. In any case, don’t skimp on the ventilation or lighting. You will need more of both than you think. A good spray gun and compressor that can provide plenty of air comes next, and don’t forget the water trap and inline water filters; water in paint is a disaster. Personal protective equipment, based on the MSDS recommendations, is a must. And lastly, a good paint job is impossible without good paint and preparation products. Expect to pay as much as $400 per gallon for high-quality paint, and more for some colors. It’s expensive, but your airplane is worth it. It won’t be easy to match what the Solesbees did, but with patience, some experienced help and a lot of hard work you can turn out a nice-looking airplane.

This detail shot of the wing shows the colors, striping and shadowing that artfully combine to present a truly amazing display of the Solesbees’ painting skills.

Next time the Solesbees will be reassembling their airplane, getting it inspected and taking it on its first flight. This is the real excitement of building your own airplane—two years of effort culminating in one moment of pure emotion. There is nothing quite like seeing your baby take off for the first time under its own power. You won’t want to miss it!

The finished fuselage shows off its new paint job in the Southern California sun. With limited space in the booth, the wings had to be painted separately and can now be reattached. You can see how many colors were used to make this Evolution one of a kind.

For more information, call 541/923-2244 or visit www.lancair.com.

Evolution became a separate company after splitting off from Lancair, Was this a (plain) Evolution or a Lancair Evolution? And in any case, Evolution is now owned by JMB Aviation in Europe with production moved to the Czech Republic, or Czechia, if you prefer.