Most pilots are, to some degree, weather nerds. We have to be. And it’s not a passive relationship. Understanding the mechanics of weather is as important as the ability to read a radar image or decode a station report. Weather is a fascinating topic not just because of the way it influences flight (and our decisions regarding it), but also because it contains so many variables. An air mass can act one way, or it can act another. Meteorologists predict, but the weather will have its way.

The Sandberg weather-station complex is visible from across the valley.

I watch weather regardless of my flying plans. Dan Checkoway’s Weathermeister site is open on my desktop computer while I work, usually displaying the area conditions for Southern California. Much of the time, it’s boring: bright summer skies; the overcast marine layer from May through August; thunderstorms in the deserts; and high winds in Burbank and Chino when Santa Ana conditions prevail. If you’ve lived and flown in SoCal for as long as I have, you learn to recognize the trends and habits of the weather. Much of the time, the excitement is in reading the pilot reports.

But Not Always

One of the weather stations that shows up on the broad Los Angeles-area briefing is Sandberg, an automated weather-reporting station (ASOS) by the identifier of SDB. Sandberg is not an airport but a remote reporting station on top of Bald Mountain in the foothills to the east of Interstate 5—landscape that motorists see only for the sprawling concrete as some intermediate point between Los Angeles and the great central valley to the north.

Rolling hills surround Bald Mountain, where the Sandberg weather station is located, influencing the movement of weather in the valley and making the station’s reports seem excitingly dire.

For me, it’s more than that. This area is a notorious weather maker. The Mojave Desert to the east pushes westward like an arrowhead into this stand of mountains, bracketed to the north by the Tehachapi range and to the south by the westernmost finger of the range that hems in the Los Angeles basin to the north. Just to the northwest of Sandberg is the Tejon Pass, at 4239 feet the highest point of I-5 as it descends northward down a section called The Grapevine.

Weather systems coming from any direction meet this unique topography and then, well, all hell breaks loose. Strong winds from the east funnel up the western edge of the Mojave, swirl over the mountaintops and make flights along the IFR airways Victor 23 and V459 more than a little interesting. There have been days when the ride is perfectly smooth in the central valley, rough as a cob over the VORs at Gorman and Lake Hughes, only to become glassy again on the descent into Los Angeles. At times strong winds from the north create perfectly smooth mountain waves with updrafts and downdrafts of 1500 fpm or more. I’ve flown through there with winds at less than 15 knots at altitude and received the roller-coaster treatment, and other times with winds at 35 knots and felt nary a bump. The difference of a few degrees of wind direction can mean everything to the little human in the 2500-pound airplane.

Rising terrain on all sides of Bald Mountain help turn moderate weather factors into something really interesting at the ASOS weather station.

Sandberg Central

By watching the hourly reports pretty much year-round, I’ve noticed an interesting trend. Often, Sandberg has the worst weather in all of Southern California. When the wind is, say, 270° at 20 knots at Mojave (33 nautical miles to the northeast), it’s 300° and 35 gusting to 40 at Sandberg. When the weather at Fox Field in Lancaster, 24 n.m. to the east, is generally good, the report from Sandberg often looks much worse.

Here’s one example. On December 19, 2011, while Lancaster reported sky clear, winds 270° at 9, Sandberg was 300 feet and overcast, visibility 2 statute miles in mist, with winds out of the south at 5. It’s changeable, too: About an hour after that observation, Sandberg turned Low IFR, visibility less than ¼ mile, vertical visibility 100 feet. In the tabular form presented by the Weathermeister web site, it’s easy to see the bad weather at a glance; Checkoway has wisely chosen to highlight certain adverse conditions in red type, with other color codes for moderate conditions. Basic, benign conditions are white type on the black background, so it’s easy to scan down the list of station reports to spot the ugly stuff.

During the active winter months here in SoCal, I’ve seen Sandberg report freezing fog, snow showers, low visibility, howling winds and some of the coldest temperatures around, in part because the station is at 4400 feet MSL—not high by Sierra Nevada standards but in combination with its unique place in the topography and access to the cold, usually dry desert air mass, it’s enough to make the reports interesting.

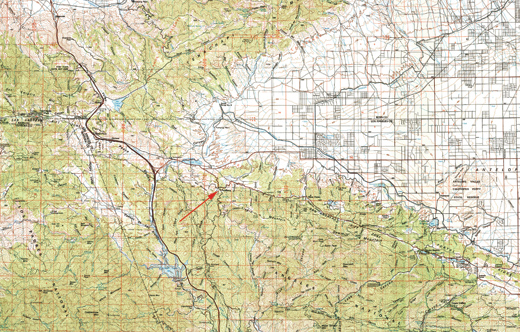

A USGS topographical map suggests how the flat, windy desert surrounding Palmdale and Lancaster, California, might influence weather in the higher terrain to the west. Sandberg is located at the arrow.

The Place, In Person

Just before the Christmas holiday, I decided to visit Sandberg myself. Sure, I’ve flown over it and perused the area digitally thanks to Google Maps and Google Earth. Airborne at 1000 feet AGL, I could make out the fenced-in weather station, but the surrounding terrain didn’t offer much of an explanation. Sandberg ASOS seemed to be located on top of a low hill, immediately surrounded by grasslands with the area’s native oaks nearby.

This is as close as you get to the Sandberg ASOS without hopping the fence.

It wasn’t until I borrowed a dual-purpose motorcycle—a BMW G 650 GS Sertão capable of light off-road duty—and rode to Sandberg that all the puzzle pieces clicked into place. Approaching from the northwest along County Highway N2, it’s obvious that the Sandberg area and Bald Mountain peak comprise a bit of topography that rises quickly and steadily from the westernmost Mojave basin; weather patterns with any kind of momentum must carry it over this rugged terrain.

I found the main road to the ASOS where N2 intersects with the Old Ridge Route, the switchback road built in 1915 as a north-south conduit along the ridges of the San Gabriel and Tehachapi mountains. A short ride down a pockmarked, mostly dirt road led to, well, less than I’d hoped for: a roped-off road heading up to the ASOS. I could see a way around the fence line but decided that trespassing wasn’t on the menu for the day.

I backtracked to the south and rode for a few miles on the Old Ridge Route, which still has pieces of concrete and asphalt in place but is mostly dirt and has clearly been ravaged by the elements. Fortunately, from there you can’t hear the hiss of tires atop the eight-lane I-5 just to the west, but you can get a view of the ASOS and its relationship to the surrounding terrain. From a half-mile away, I had an epiphany. Sandberg ASOS stands proudly atop Bald Mountain. Looking to the north, to the west, and to the south, it’s obvious that there’s nothing much to stop weather ripping across the hills and striking the sensitive equipment full force. Moreover, its location on top of the mountain explained how the nearby desert airports could report good visibility when Sandberg’s data stream suggests a full sock-in. (With freezing rain, snow pellets, vermin and locusts, for all I know.)

I was quite surprised to see how Sandberg looked from the ground. In my mind’s eye, I had the station in a shallow, clear valley with trees surrounding it on hillsides. I should have been looking at a true topo map, not just the satellite view. For all the times I wondered why anyone would build an intermediate weather station in such a valley, I now know precisely why someone would build it on top of Bald Mountain. Besides being a lot more useful in forming a mental picture of weather across this interesting and ever-changing microclimate, it’s a whole lot more entertaining.

![]()

Marc Cook – Former KITPLANES® Editor-in-Chief Marc Cook has been in aviation journalism for 23 years and in magazine work for more than 25. He is a 4500-hour instrument-rated, multi-engine pilot with experience in nearly 150 types. He’s completed two kit aircraft, an Aero Designs Pulsar XP and a Glastar Sportsman 2+2.