Ever consider what it might be like building an ultralight? But first, how do ultralights fit into the arena of “regular” Experimental airplanes like the ones featured here in KITPLANES? For those not familiar with the technicalities of an ultralight, allow me to briefly summarize the details of what defines an ultralight. Then we’ll consider how they complement their larger brothers.

Ever consider what it might be like building an ultralight? But first, how do ultralights fit into the arena of “regular” Experimental airplanes like the ones featured here in KITPLANES? For those not familiar with the technicalities of an ultralight, allow me to briefly summarize the details of what defines an ultralight. Then we’ll consider how they complement their larger brothers.

While you may hear pilots and builders use the term ultralight to describe a small, light aircraft in general terms, the FAA has very specific rules as to what constitutes an ultralight. Full details are spelled out in Part 103 of the FARs, but here are the highlights.

An ultralight has a single seat (pilot-only capable), an empty weight of no more than 254 pounds and a maximum speed of 63 mph. So, if you ever see a small plane with more than one seat, or one that obviously weighs more than 254 pounds, that aircraft does not meet the legal criteria of an ultralight.

In addition, an ultralight does not receive an airworthy certificate from the FAA (so it is never inspected) and does not require a pilot’s certificate to fly. (Be careful with that rule!)

I think the idea of an airplane you can build without FAA involvement and fly without a license is very appealing. The ultralight regulations are truly an amazing privilege in the U.S. and allow many people to experience and experiment with flying.

This brings me to how ultralights fit in with other aircraft. I contend that ultralights are a gateway for people who are toying with the idea of building and flying larger kit aircraft. Many an ultralight enthusiast has gone on to build a full-size Experimental. At the other end of the spectrum, ultralights allow experienced pilots and builders to fly inexpensively without medicals, licenses or yearly condition inspections. It’s flying—just for fun.

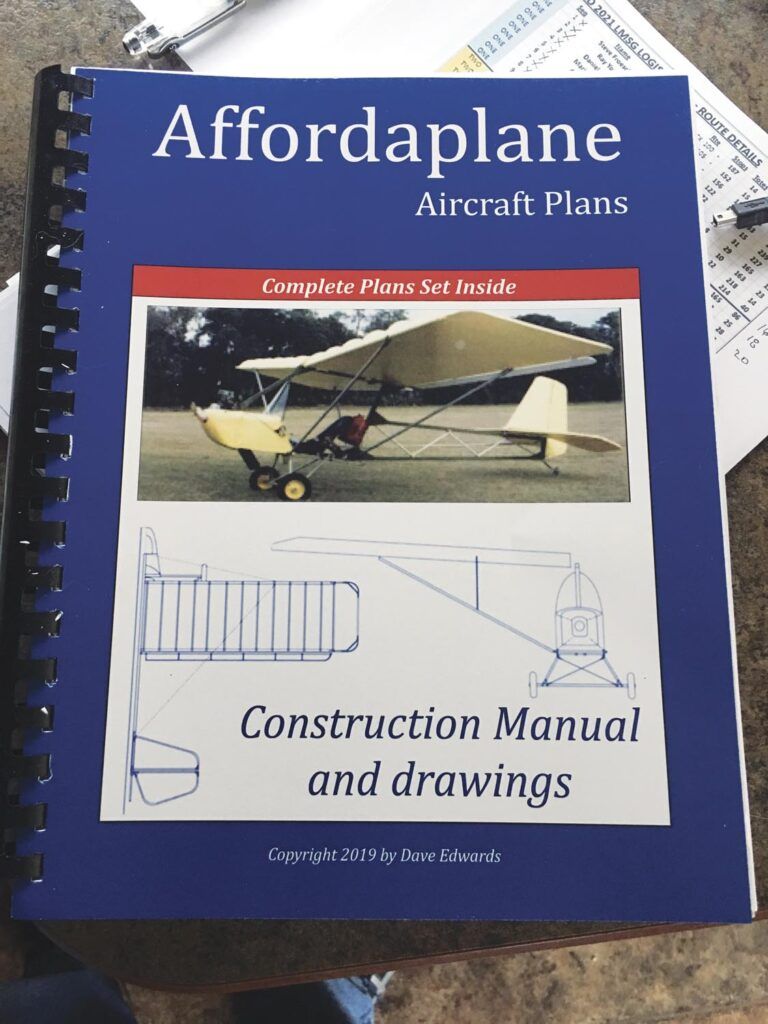

While there are many ultralight kits available, there are not a lot of plansbuilt choices. After some research, I settled on a design that offers a complete set of plans on paper or electronically in PDF format. It is called the Affordaplane and it was created by Dave Edwards.

You can learn about the Affordaplane at www.affordaplane.com, and more research can be done via Google. I was attracted by the evidence of more than 20 years of flying history, along with YouTube demonstrations. I admit that I did not invest too much effort in researching this choice, but the $20 cost for the set of plans allowed me to dive right in for the purchase. What followed was an order to Aircraft Spruce for some tubing and the start of a journey of building. Raw materials, along with my prior kitbuilding experience, allowed me to scratch build a flying ultralight just like the plans promised within a year.

I had a secondary purpose for taking on this build. You see, I began my own flying and building skills by way of the ultralight. I had built and flown two ultralight kits before obtaining my private pilot ticket back in the 1990s. I was aware that others could also benefit in this manner and eventually move on to bigger and more challenging avenues with Experimental planes. I felt that if I could show others how to assemble an ultralight aircraft using the same materials and techniques that an FAA-inspected Experimental aircraft needs to earn an airworthy certificate, then I would be providing others with an example that could pave the way to building larger flying machines.

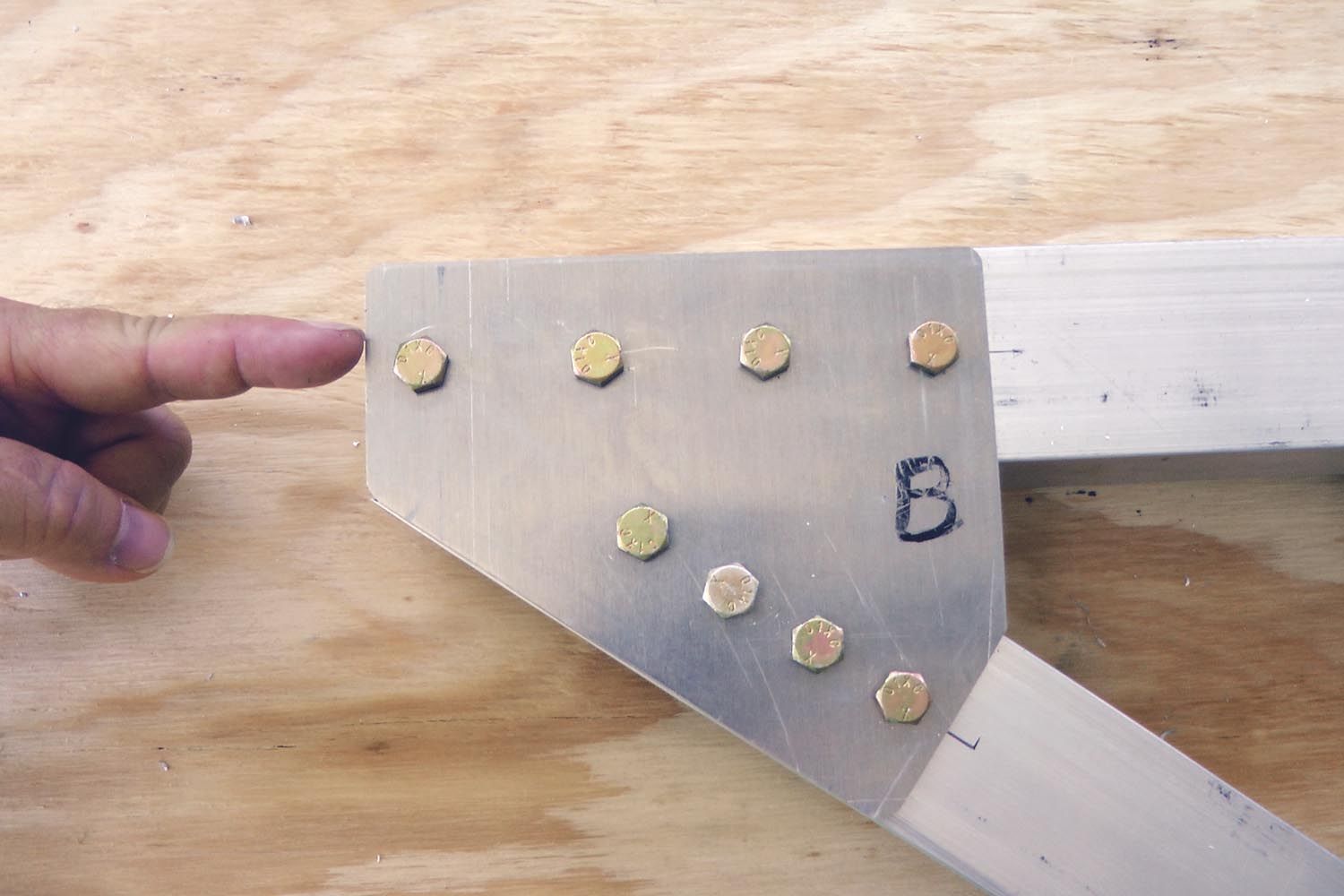

For instance, as the Affordaplane is not a kit and fasteners are not supplied, it is easy for the novice builder to consider using hardware store nuts and bolts. The plans do specify AN hardware—but a new builder may not know or consider why this is critical. My experience with Experimental aircraft construction could allow me to explain and demonstrate proper parts and techniques required at each step of this ultralight build.

How best to share my construction techniques and demonstrations while building this ultralight? The answer was YouTube! I made it a goal to film and explain every step of building, which created a series that anyone could follow if they also wanted to build this machine. About one video per week was my pace (I was building behind the scenes in real time) and then I summarized and demonstrated the effort needed for each step. In approximately one year, the entire ultralight was finished and flown (just a crowhop; I am not a flight instructor and that was the extent of flying demonstrations from me). This 50-part series is free of charge to watch on YouTube.

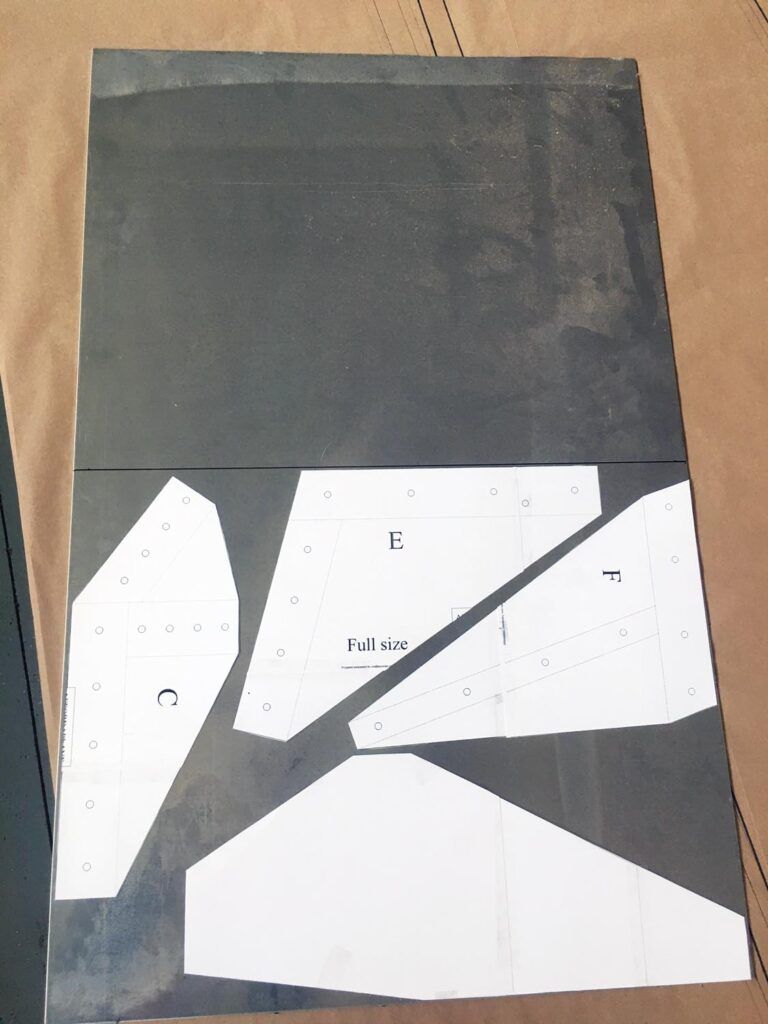

A full-size layout is drawn on the table prior to assembly.

Perhaps the most important requirement of any plansbuilt ultralight is meeting the legal weight requirement of FAR Part 103—less than 254 pounds. It is both a building and design challenge to make sure things are created strong and light. It wasn’t easy, but I always kept this goal in mind. There was no way to know in advance if I was successful until the last part was installed and the weight and balance recorded.

In future columns I’ll discuss some of the problems I faced while building the Affordaplane. Whether you have time to watch the videos or just fast-forward through several of them, you’ll get an idea of the skills needed to complete the project. Drilling, cutting, riveting, crimping, fabric covering and lots of AN hardware assembly are all required. These tasks are no different whether building an ultralight or a complex Experimental aircraft. Plane and simple!

I followed your Youtube series, Jon. Excellent work – both building and filming. Thanks. My choice for a part 103 will be a Eagle Eagle XL – I’m comfortable with oxy-acetylene welding thin wall chrome moly tubing an I like the more conventional structure. It is also a well proven design with lots of community builder support (though not as well documented as your build).

I think this is a fantastic article! The A-Plane beats the others hands down. While the Legal Eagle is a nice flying airplane, having to learn to weld is a costly and time consuming process. It takes years to become a good aircraft welder, and you are never sure of your welded joints strength. Plus the performance on a half vw motor is marginal.

With the A-Plane, you cut out flat pieces of metal and bolt them to square tubes, and you are done. Many people build their fuselages in one weekend. And you are guaranteed the strength. There is no question, no doubt. I think that is why the A-Plane is so popular, and other companies try so hard get some of her attention. Great article thanks!