“One-thousand unrelated miracles occurring in the proper order.” That was how my squadron life support officer described how the F-4 Phantom’s Martin-Baker ejection seat functioned. In another briefing on another subject, our squadron weapons officer used the same phrase to explain how an AIM-7 Sparrow semi-active radar-guided missile worked.

These lessons took root early in my career as an Air Force F-4 weapons systems officer, and they made perfect sense to me. The seat’s and the missile’s proper function required specific mechanisms to correctly operate in the correct order. If anything happens out of sequence, then the entire sequence may fail.

Hey, it’s no different when it comes to building and flying an airplane. We build certain components before others. We build up and install the engine before the baffles. We usually build the fuselage before that, so that we’ll have a place to hang the engine. It’s usually smarter and easier to install the wing lights and wiring before mounting the wings to the fuselage.

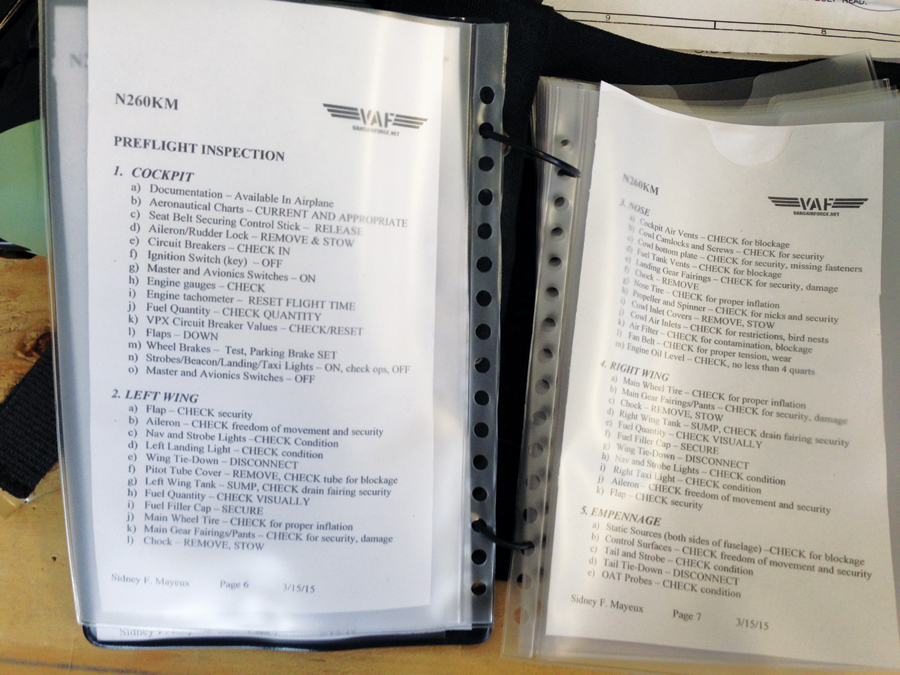

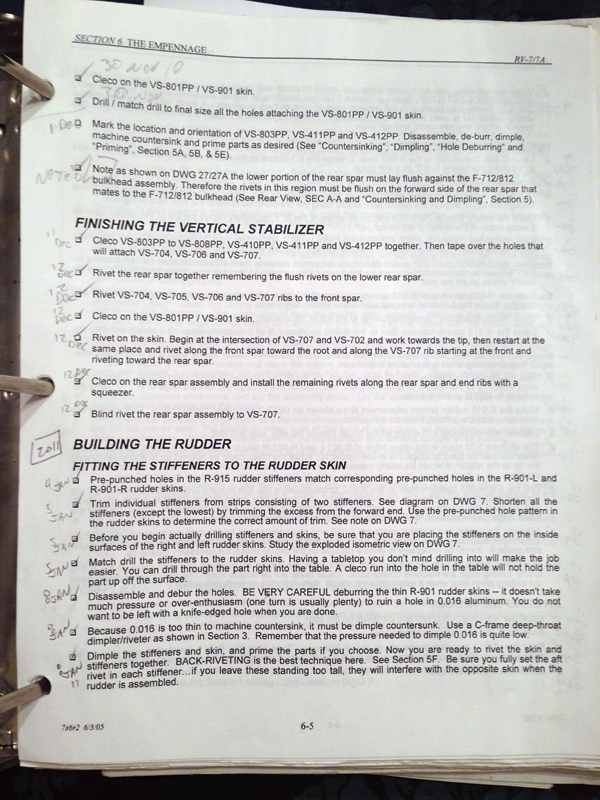

Most all aircraft kits come with a construction checklist in the form of a builder’s manual. My RV-7A build manual was a real lifesaver. I learned early that I could successfully complete a reasonably well-crafted aircraft part or assembly if I stuck closely to the steps outlined in the manual. As I completed each step, I checked it off in pencil with a completion date, which made it possible to find the dated photo entry in my KitLog Pro builder’s log.

We use checklists in the airplane to make sure we cover all required actions, and in the proper order. For example, for fuel-injected engines, our checklists have us engage a fuel boost pump before takeoff to lessen the chance of fuel pressure loss. We write fuel/air mixture adjustments into our climb, cruise, and descent checklists.

Now, to be clear, the FAA doesn’t actually require operators to build and use an aircraft checklist. However, I contend that a well-operated aircraft should have a well-built and executable ops checklist. Furthermore, a conscientious pilot runs the checklist every time, either directly from the printed page, or from memory (but then verified by referencing the checklist). A pilot running the checklist builds his passenger’s confidence and comfort. And a pilot comfortable and versed in running a checklist is more likely to successfully and accurately run an emergency checklist when the going gets rough.

The Checklist’s Origin

In case you haven’t heard the story, checklists were invented after a 1935 bomber crash at Wright Airfield (now Wright-Patterson Air Force Base). Boeing launched their sleek four-engined Model 299 bomber as their entry to an Army Air Corps bomber competition. At the time (only 33 years after the Wright brothers flew their E/A-B project), the Model 299 was the most complex aircraft ever built. Yet pilots had to know their jobs by heart, and checklists didn’t exist.

On that autumn day, the pilots forgot to release a new locking system on the empennage flight controls. The bomber roared steeply into an uncommanded climb after takeoff, then stalled and crashed, killing two of the five crewmembers. This nearly doomed Boeing’s chances at winning a contract for its bomber.

Checklists were invented after the Boeing Model 299 bomber crashed in 1935. The pilots forgot to release a new locking system on the empennage flight controls. The design eventually went into production as the B-17 Flying Fortress.

After the event, Boeing engineers recognized the greater array of tasks required to pilot this machine. By organizing these tasks into a checklist format, they transformed aviation and aerospace safety in ways that echo through all levels, from Cessnas to space shuttles. They revived the 299’s potential, saving the airplane’s place in history as the B-17 Flying Fortress.

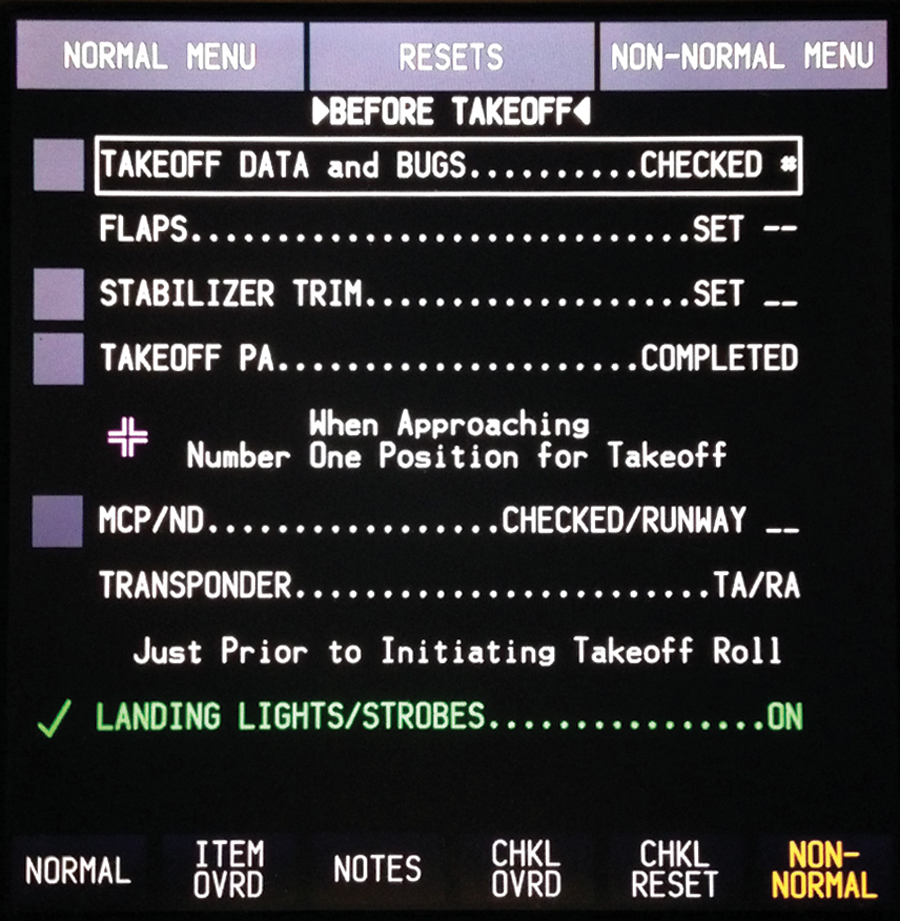

The Boeing 777-200ER electronic checklist, displayed on the lower center multi-function display. Items with grey boxes are open loop items, so the pilot must check it off. Other items are closed loop; the system senses the proper switch or handle position, and checks off the item. Green items are complete.

Boeing’s checklist heritage continues to this day. Take for example the Boeing 777 airliner. In my job as a Triple-Seven Ground School Instructor at American Airlines, I teach upgrading captains and first officers how to run the big airliner’s electronic checklist (the ECL). The crew can call the ECL up on any of the three multi-function displays, and it will run in order—from Before Engine Start to Parking. The ECL features two types of checklist items: open loop and closed loop. For closed loop items, the airplane senses the applicable switch position. If it’s in the right position, the checklist “greens up” the item, and the pilot need not call it out. Open loop items require pilot action, and then he clicks off the item with his cursor and moves on.

For such a modern, automated piece of machinery, the 777 is surprisingly checklist-oriented. Pilots soon realize that the checklists exist to make sure all actions and systems are properly configured and are working properly. Pilots have great trust in this fine Boeing machine, but the checklist helps them verify that all unrelated miracles are indeed occurring in the proper order.

Memory Items, Boldfaces, and CAPs

Have you written critical action procedures into your POH’s emergency section? Some emergencies (like fires and engine power loss) require immediate pilot action to remedy the situation, keep the situation from getting worse, or stop the problem before it becomes unstoppable. For decades, aircraft builders and operators included special checklist steps and recommended pilots commit them to memory. The Air Force prints them in bold print and calls them boldface items or CAPs—Critical Action Procedures. American Airlines draws a red hashed box around them and calls them simply “memory items.”

The space shuttle’s Orbit Pocket Checklist (nearly two inches thick) provided immediate actions for malfunctions and emergencies.

In all cases, pilots have to know them by memory to get to fly the airplane. Airline and military pilots are tested on the steps; 100% is the minimum passing grade. When I flew the mighty Phantom, I had to complete a handwritten boldface exam on the first flying day of every month. If I incorrectly wrote any item of the memory test, not only would I not get to fly, but I also would have to explain the test failure to the squadron commander. To this day, I remember all of the F-4 boldfaces, such as the boldface for a takeoff abort (Throttles—Idle, Chute—Deploy, Hook—Down). I never failed a boldface exam. Never. Ever.

The boldface was gospel: You never deviated from it. But what if you face a situation when, at that moment, a checklist step actually creates a greater or new hazard? This is that part of the movie when the pilot must earn his flight pay. If the emergency—or multiple compound emergencies—makes it necessary to deviate from the checklist, the pilot should exercise good judgment and deviate. Don’t make the situation worse.

The author’s construction manual. Note the completion dates, which served as a backup record for his formal builder’s log.

Rolling Your Own Checklist

Although not required for E/A-B aircraft, it’s a very good idea to build a POH for your airplane. That POH can serve as the basis for your flight checklist (if you build one). There’s nothing wrong with printing the checklist on good old-fashioned paper, perhaps protecting it by laminating it at Kinko’s or sticking it inside plastic sleeves.

Today, however, we live in a more modern flying environment. Kitbuilders have dozens of app options to load their checklists into their iPads, tablets, or other electronic media. One simple solution involves building your checklist in Microsoft Word, saving it as a PDF file, then loading the PDF into iBook. The pilot can then open the checklist in iBook, and even execute the finger-spread maneuver to enlarge the text.

Typing “aviation checklist” into an app store search yielded 30 results, many of which are customizable to our E/A-B needs. For instance, FltPlanGo (from Flight Plan LLC) has a great checklist feature, is fully customizable, and even has a voice feature that can “read” the checklist items to you over your intercom.

All safety aside, for me, here’s the best part: Of all the positive aspects a checklist brings to my airplane, I look forward to the crew concept most of all. When I finish the Phase I fly-off, my bride Kelli will become my copilot. You can bet I’ll put her to work, making her a part of the crew. Oh, I’ll have my own checklist handy, and I’ll implement boldface memory items into the emergency section. But I want her to run the normal ops checklists; she’ll call the items, and I’ll run the switches. I think she’ll appreciate the chance to be more than just the passenger.

After all, if there’s anyone that insists I accomplish things in the proper order, it’s my Kelli Girl.

Note: All references to actual crashes are based on official final publicly-released NTSB and Air Force Accident Investigation Board reports of the accidents, and are intended to draw applicable aviation safety lessons from details, analysis, and conclusions contained in those reports. It is not our intent to deliberate the causes, judge or reach any definitive conclusions about the ability or capacity of any person, living or dead, or any aircraft or accessory.