“For all sad words of tongue and pen, the saddest are these, ‘It might have been.'”

—John Greenleaf Whittier

It would have been great if all 13 original entrants in the CAFE Foundation’s Green Flight Challenge had shown up at Santa Rosa, California, during the last week of September 2011. The collective creativity and craftsmanship would have certainly dazzled, and the cross-pollination would have bred many new and exciting concepts for future developers.

But the four entrants that did make it provided enough excitement for all in attendance, and the results were certainly a sign of things to come. Still, one wonders of the other possibilities and what they portend for the future of general aviation. We’ll look at those possibilities, because they are promising aircraft literally waiting in the wings for their moment of glory.

Synergy’s roomy cabin has space for at least three more people.

John McGinnis, Synergy

If anyone has generated intense interest in new aerodynamic approaches, it is John McGinnis, a Montana-based designer and builder with a controversial blend of theory and practice that promises unprecedented speed and flexibility. His plan to win the GFC included a six-passenger equivalent load and “twice the best economy speed,” two-upping Pipistrel. Coyly avoiding specific performance statements yet to be proven, McGinnis is not shy about giving the impression that he would have won the event.

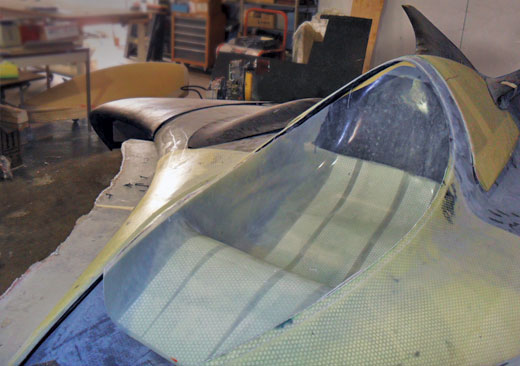

John McGinnis, family and friends vacuum-bag one wing panel for Synergy.

That would have been in a one-off prototype meant primarily for the competition, however, and the lack of GFC pressure has allowed him to return his attention to a more practical kit prototype, including tooling for a series of pre-production prototypes to sort out the many details that make a successful GA aircraft. Successful demonstrations of the airplane may help entice investors and provide a solid financial grounding for the enterprise. Pictures on his Facebook page show an extra-large cabin, well-designed details, and a large and enthusiastic group of family and friend volunteers. He also notes that updated performance calculations show Synergy would have defeated the other Green Flight challengers.

Synergy’s multifunction nose cone shows the level of detail on the aircraft.

A well-done slideshow promises “triple the fuel efficiency of competing designs,” and double the speed “without the limitations of long wingspan, fast landings, small engines or cramped cabins.” The assertion that this can all be done with a 200-horsepower diesel engine gives some sense of the lightweight structure McGinnis is hoping to achieve, and explains why helpers have flocked to his Montana enclave to support this pioneering exploration of “powered aerodynamics.”

Despite setbacks, McGinnis has an optimistic view of Synergy’s future, a future many are contemplating with great hopes. His straightforward approach and well-reasoned presentations have made many converts, including those who would have been his strongest opponents in the GFC.

Greg Cole, Windward Performance

Cole has been tight-lipped about his company’s promised entry, the DuckHawk. He had originally intended to enter the GosHawk, a sleek two-seater that had overtones of Lancair in its lines—not surprising because he once worked for that firm. Its 50.8-foot span, 83.6-square-foot wing gives it an aspect ratio of 30.8:1 and a sink rate of only 130 fpm at 46 mph. With its eyebrow-raising 480-pound empty weight, the HKS 700E two-cylinder powered craft will be an economical way to tour or go gliding, using only two-thirds of a gallon of gasoline to travel 100 miles in an hour at 300 passenger miles per gallon (pmpg). It would not have won the contest, but as a viable commercial vehicle, it should be popular with owners and flying schools. Cole continues to work toward an electric realization of this airplane, a motorglider/Light Sport Aircraft that would provide extreme economy of operation.

The DuckHawk became an alternative because Cole thought GFC rules favored electric craft, and he was eager to develop one. A variant on his popular SparrowHawk sailplane, the DuckHawk would have a standard-class wing that, with its low weight, would require little power to achieve the necessary cruising speed. Unfortunately, Cole could not make even the second deadline for the contest. Both the pure sailplane and electrically powered version will be available in the not-too-distant future, though.

Gene Sheehan, Feuling Green Flight Challenger

While many are reticent about specific performance numbers for their still-to-be-tested aircraft, Gene Sheehan is happy to give detailed information about the development, status and demonstrated performance of the Feuling Green Flight Challenger. Derived from Sheehan’s, Tom Jewett’s and Burt Rutan’s original 1977 Model 54 Quickie, the new airplane has a PMG brushed electric motor and natural laminar flow (NLF) airfoils, cutting cooling and aerodynamic drag from the original design by 30%.

Two 1.25-inch holes in the cowling provide all the cooling air necessary for the electric motor and controller on the Feuling Green Flight Challenger. Its clean lines show clearly here.

The motor, which Sheehan says costs around $1000, is controlled by an Alltrax unit normally found on golf carts and neighborhood electric vehicles; it’s capable of 19 hp at full tilt, but only for about 10 minutes, being temperature limited for such output. It can run on 74 volts at 110 amps continuously (8.14 kilowatts or about 10.9 hp) without stress. Sheehan explained that it takes only two 1.25-inch holes in the cowling to adequately cool the motor and controller.

Power comes from three to six 30-pound battery packs, depending on how far one wants to fly. An hour around the pattern requires three: two in front of the firewall and one in the original fuel tank’s location under the pilot’s knees.

The Challenger can hit 160 briefly, and on its continuous rating of 100 amps cruises at 119 mph. Sheehan had planned to run at 105 mph for the contest, running six battery packs to give the necessary range, with two under the pilot and two on the bulkhead behind the seat. Charging the three packs for an hour’s flight, based on his electric bill, costs $1.58, making that weekend hamburger flight more reasonable than ever. He said that potential electric-aircraft pilots will need to look at upgrading their house’s electrical system, because even 20-amp breakers cut out under a charging load.

Economical at all levels, the Challenger had total development costs of about $65,000, and Sheehan agreed that a kit might be possible for a reasonable price. The big cost for potential builders would be the batteries. Seven packs (six maximum in flight plus a spare) provided reputedly at cost by the supplier totaled $17,000. Sheehan feels that batteries are the weak link in a promising technology, and that even a 2x jump in cell performance would have a profound effect on the market.

Asked how the Feuling craft would have fared in the GFC, Sheehan good-naturedly said he thinks he would have been competitive, “But I wasn’t there.”

Richard Ike and Ira Munn, Seraph

Having met Richard Ike and Ira Munn at the GFC Expo at Moffett Field in early October 2011, I can attest to their earnest commitment to their angelically named creation. Munn has supplied current photos of the airplane under construction, showing a 7-foot, 8-inch wide fuselage (with the wingroots) with a low V tail and 3-feet, 8-inch removable outer wing panels. The whole span is 15 feet. Dismantled, the craft can be moved on a trailer as necessary.

A front view of Seraph shows its F-117-like lines.

Nested now in EAA South Bay Chapter 96’s hangar in Los Angeles, the airplane is surrounded by other chapter projects, but it gets the benefit, Munn said, of the tools, expertise and support the organization can provide. Al Timmons is responsible for the interlaminar structural framework of the composite skins, their material, and layer selection and fabrication. With top and bottom fuselage skins being pulled from the CNC-fabricated molds created by Guy Martin Wenzel of Guy Martin Design and prepped by Al Timmons, the aircraft’s bird-like form becomes apparent.

This high view shows where the outer wing panels separate from the main fuselage on Seraph.

Seraph’s lifting body/blended wing shape was designed by Richard Ike, 3D-modeled by Rudy Ramcharan and 3D-mastered by Shawn Moghadam. Naimish Harpal of CFDmax was responsible for the computational fluid dynamics analysis. Noe Ramirez faced a challenge installing bulkheads in the lower fuselage half, because as Munn said, there are no straight lines anywhere on the fuselage.

Timmons created molds for the eleven-blade props, and Dietrick Alkonis made the prop hubs, which will be housed in ducts on the rear of the fuselage. Thrust will come from electric motors, the last part of a hybrid diesel-electric chain designed by Andre Williams of Regenerative Electrical Power Systems, Inc., which must be concealed for now.

A closeup of the Seraph cockpit shows the complex arrangement of different fibers, composites used in construction.

A fixed landing gear, with a nosewheel and an outrigger-type wheel under each wingtip, are neatly faired. The cockpit fits its single occupant tidily.

Seraph’s design philosophy will be put to the test soon, with Dave Morss (one of the winning pilots of the GFC) and former Air Force Test Pilot Merrill Eastcott volunteering to guide the plane on its initial flights. Following success in that realm, the next step may be for an investor to help make the airplane a commercial reality.

Paul Lucas, Greenelis PXLD

The Greenelis PXLD was to be the sole French entry in the GFC, and it was exhibited at the 2011 Paris Air Show. With a wingspar built of carbon fiber with “innovative geometry” and a wing covered with plywood, Greenelis spans 11 meters (35.2 feet). Its fuselage has wood formers and longerons, and a plywood outer shell giving it its aerodynamic form.

The two-place side-by-side aircraft is powered by an 800cc Mercedes Smart Car turbocharged diesel engine that produces 30 kilowatts, or 42 hp. A single retractable, centerline landing gear (with outriggers) helps give the 275-kilogram (605 pounds) empty-weight airplane a 220 kilometer per hour (136.4 mph) top speed and a 160 km/hr (99.2 mph) cruise, at which its consumption is 1.8 liters per 100 kilometers (130.7 mpg), or 261.4 pmpg. This meets that GFC criterion, but as recent history demonstrates, falls short of winning performance.

Lawrence Speer was to be team leader for the GFC, and designer Paul Lucas helped construct it, along with Bernard Stervinou and Arthur Nirma. Alain Raposo developed the powerplant and its reduction gear, and Romain Lucas managed electronics. Julien Stervinou was responsible for the contest flight strategy, and Pauline Stervinou provided publicity for the project.

Greg Stevenson, GSE-Aerochia 3000

Greg Stevenson’s high-efficiency hybrid design is known as the GSE.

Greg Stevenson makes jewel-like innovative heavy oil powerplants at his Lake Tahoe machine shop, and was to power his GFC entry with a small unit that would be part of a highly efficient parallel hybrid system. Working on the design of the system with Dr. Andrew Frank of the University of California at Davis, the pair envisioned an airplane efficient enough to not only be competitive at the GFC, but to circumnavigate the world on 125 gallons of fuel, according to a discussion with Frank last year. (The Rutan Voyager required more than 1100 gallons.)

An adjustable propeller and excellent machining mark GSE design and execution.

The GSE entrant would, along with Synergy, exploit Goldschmied propulsor technology with thrust coming from a pod thruster and from an electrically driven prop aft of the tailboom-mounted rudder. Able to make the “heavy” composite shells for the aircraft, Stevenson had not yet made the “light” carbon-fiber-based assemblies that would have helped provide the light weight necessary for the competition. Nevertheless, GSE’s mockup did appear at the Google-sponsored Green Flight Expo at Moffett Field and drew a great deal of attention for its slender form.

Like Synergy, the GSE aircraft would use Goldschmied propulsor for additional thrust. See the CAFE Foundation library for papers by Goldschmied (www.cafefoundation.org).

The Yuneec E1000

Tian Yu, chairman for Yuneec, said the four-seat, twin-motor airplane would be flying in the GFC. The prototype was being tested by Martin Wezel, a German designer and pilot, when he was killed in the airplane outside Shanghai, China, in May 2011. Yuneec withdrew from the competition.

Calin Gologan, Elektra One

PC-Aero’s Elektra One had been flying in Germany and at Oshkosh, so the airplane’s withdrawal from the GFC was a large disappointment. PC-Aero had plans for Elektra One to be flying with a full complement of solar cells, and being recharged by its solar hangar this spring. The plan is to appear at Aero Friedrichshafen 2012, and be joined in the air by Elektra Two this year.

PC-Aero’s Elektra One appeared at AirVenture 2011. Solar cells were mounted, but they’re not connected here.

Mike Stude, Wings of Salvacion

Named for the builder’s wife, the ethanol-fueled Quickie derivative would have added yet another power source to the competition.

This Year and Next

Most creators behind these airplanes say they are moving forward, and have every intention of seeing their ideas fulfilled. This bodes well for the near future, and EAA’s AirVenture 2012 may benefit from the presence of the aircraft that were not able to attend the GFC. Who knows what the 2013 event will bring?

![]()

Dean Sigler has been a technical writer for 30 years, with a liberal arts background and a Master’s degree in education. He writes the CAFE Foundation blog and has spoken at the last two Electric Aircraft Symposia and at two Experimental Soaring Association workshops. Part of the Perlan Project, he is a private pilot, and hopes to get a sailplane rating soon.