So why do I need a pre-buy inspection, you ask? You’ve already seen the airplane, you really like the paint scheme, and the panel has most, if not all, of what you want. And you went and flew it for 30 minutes and it handled great!

I would ask how many of you got married after one date, but I fear there is always one who will raise his/her hand. Instead I will share with you some of my thoughts on the need for a pre-buy inspection and why I think they are becoming even more important as time passes on. Then you can decide if you should take this step prior to buying. Remember, we’re supposed to be having fun here, so no sense taking the beauty home, only to find out it wasn’t all that we thought it was.

My experience has led me to believe there are three critical areas that need to be closely scrutinized: the airframe, the engine compartment, and the aircraft wiring/plumbing. Each area has its own areas of specialty. And to accomplish a good pre-buy, the aircraft should be opened up as if ready for a condition inspection, and performed by a knowledgeable and experienced person relative to the specific aircraft.

I like to start with the airframe, which is a little different than in the certified world. Why? Because Experimental/Amateur-Built aircraft aren’t built on assembly lines where we can be reasonably sure that everything aft of the firewall is the same. Here we can be reasonably assured that every aircraft is going to be different. A good place to start is with the tail, as that is where the builder usually started, and this is where you can see how the progression of skills begins.

Notice the hairline crack on the nosewheel wheelpant bracket? The aircraft was flown extensively off grass, and the axle through-bolt was not torqued properly.

There are some critical holes in the tail that don’t leave a lot of room for proper edge distance if not done carefully. I have seen some tails on aircraft that had bolt holes mis-drilled and covered up, and some even missing bolts and rivets. I have seen one that I thought was not even airworthy enough to be flown home. I had one customer whom I really felt sorry for, as he had purchased an aircraft sight-unseen. The workmanship was really bad and it took him a while to make things right, eventually reselling it.

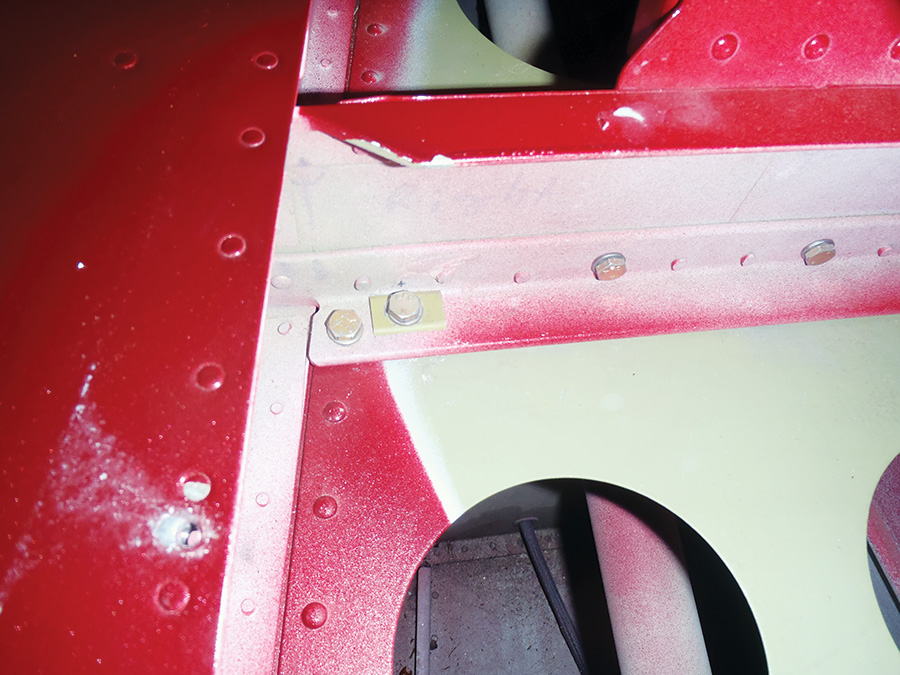

The rear spar bolts are another very critical area to check for proper edge distance. I think it is important to check and see if the aircraft has been built according to plans, or if there have been any modifications-especially those that might affect the structural integrity, such as drilling holes into longerons for equipment without adhering to edge distance rules, or removing too much bulkhead material behind the instrument panel to fit all of the whiz-bang equipment.

The landing gear is another area to check, especially if the airplane has been routinely operating off of grass or unimproved strips. These types of operations do take a toll and lead to cracks in weldments and wheelpant brackets, as well as corrosion due to the moisture from dew or wet grass. A good cleaning, followed by an inspection with a bright light and magnifying glass, will usually do the trick here.

On fabric aircraft the age and type of fabric, as well as the covering process, should be considered. With regards to composite aircraft, checking for bad bonds and/or possible delamination in structural areas should be a high priority. Again, an aircraft-specific knowledgeable person is critical.

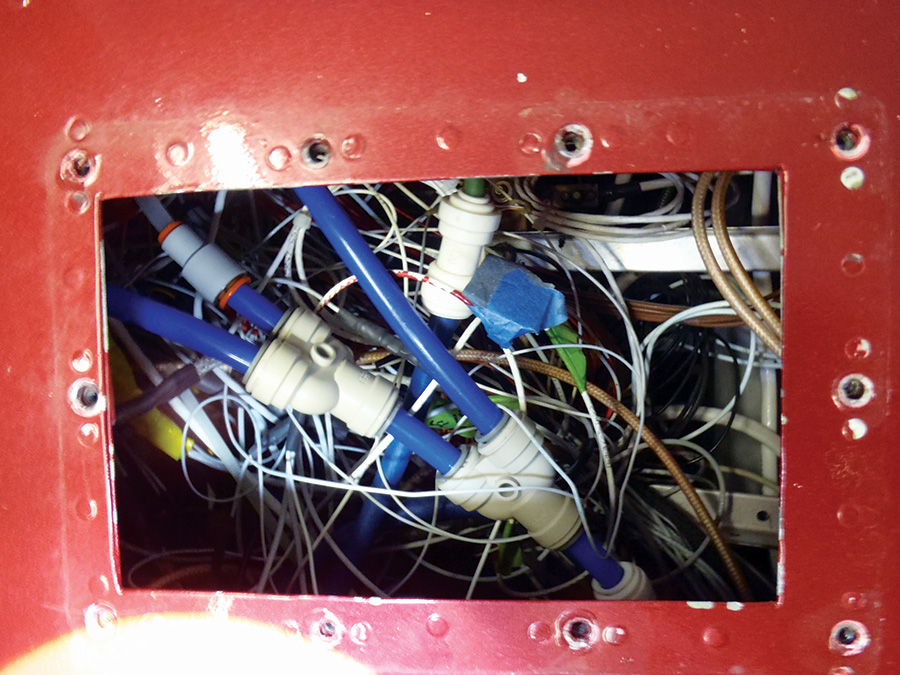

When it comes to plumbing, wiring, and systems, my experience has shown that these aren’t really the strong areas for a lot of builders. The proverbial rat’s nest of wiring can make it difficult to chase down problems, and sometimes is the source of unexplained gremlins, such as instrument gyrations when the microphone is keyed. It seems not everyone understands that the rubber motor mounts not only dampen the engine vibrations, but also electrically isolate the engine from the airframe, thus requiring a bonding strap from the engine to the mount/firewall to insure electrical continuity. And just because the bonding strap was initially installed doesn’t mean it is still intact. It needs to be checked regularly for structural and electrical continuity. I really like it when I see two bonding straps.

Sometimes I see prospective buyers thinking they are going to buy a cheap airplane and spend money upgrading the panel, not realizing that it could be a much more time-consuming and costly job than anticipated. In some cases, it could take a substantial amount of rewiring, including having to replace all of the old copper automotive wire with aircraft-grade wiring and proper grounding in order for the new stuff to work properly. Sad to say, but electrical systems seem to be a problem for many builders. And the simple electrical needs of early VFR-only aircraft are a far cry from the requirements of all-electric glass panels and entertainment systems in today’s aircraft. Wire routing, antenna distances, and grounding are so much more critical to insure proper performance and reliability.

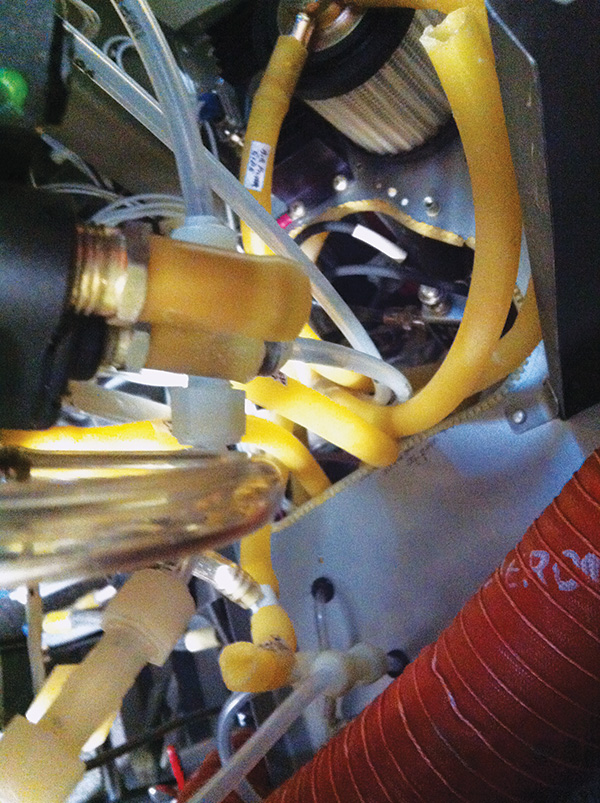

Look closely and you will see that the aged and fragile surgical tubing is no longer connected to the instrument. This was on an airplane that was regularly flown IFR without an autopilot!

I’m also seeing a common theme among the older types of aircraft, especially RVs. Early RV kits were a far cry from the pre-punched kits of today. And many of the pre-punched parts in today’s kits actually had to be made out of raw materials, requiring more refined metalworking skill sets, as well as an understanding of the various types of metals and where and how they could or could not be used. I don’t mean this as disparaging in any way, but I think the last generation was more frugal when it came to aircraft building. It was a generation without a lot of extra spendable income, so build times were longer, and there were many trips to OSH scrounging for the deals in the Fly Market. I know-I was one of them! I’m seeing this show up now as the fleet ages and many of these builders are selling their airplanes. I see a lot of surgical tubing behind instrument panels that has become very brittle with age. When used in vacuum systems it is a recipe for disaster. I’ve recently seen hoses with date stamps of 3Q 76 going to oil coolers. Sloshing compounds in wing tanks are also prime candidates for problems. The bottom line on the airframe is to make sure it is solid. While all things probably can be restored to flying status with some time and money (Glacier Girl is certainly a prime example), most likely you are not interested in that type of project. Fixing a poorly built airframe can take a lot of time, unlike an engine compartment, which can be completely replaced in a couple of days.

Holes drilled without bolts installed, bolts installed where they shouldn’t be, and bolts not installed where they should be! There are four washers on one bolt, but the maximum is three. This is not even airworthy, yet was signed off as having done snap rolls in the logbook. Can you say “lucky?” Aircraft was represented as “high-end” and the seller was asking a premium price.

Speaking of the engine compartment, let’s zero in on some prime candidates in this area. Certainly a compression check and a visual/sensory check of the oil, as well as cutting open the filter, should be mandatory. Lots of kudos here for builders/owners who have had the aircraft on an oil analysis program! Looking at the spark plugs will also yield some clues as to how the fuel and ignition system are working, as well as some insight regarding internal cylinder health. Are they oily? Worn? Lead fouled? Be sure to check the baffling for security and cracking, the engine sensors for proper mounting, and the oil and fuel hoses for age and wear. Don’t forget to check the propeller leading edge as well as the spinner, and especially the spinner bulkheads for cracks. And here’s a couple of things that routinely get overlooked: the carburetor or fuel servo inlet screens, the gascolator screen, and the oil sump screen. I had one original O-320 (no dash number) on an RV-6 that still had the original blue paint on the oil sump screen AN-900 crush gasket. Hard to believe, but it appears that I was the first one to remove it in many, many years!

The rubber motor mounts are also an area that needs looking at for two reasons: they do age, and some builders used less-than-ideal rubber mounts, for the initial installation. I’ve replaced a number of these with real Lord mounts, and the owners really notice an improvement with regards to engine vibration.

In the end, a list of discrepancies should be presented to the prospective buyer, and any potential safety issues should be discussed with the current owner. Some may need to be fixed right away, and some may be able to be addressed in the future as a budget allows. Either way, everyone is more informed, and hopefully the flying fun can begin!

I have been discussing an idea with other contributing editors at KITPLANES regarding a potential rating system in the three areas I mentioned (airframes, powerplants, and systems) that should help buyers and builders rank an airplane. I’ll go into detail in a future article, but here’s the general idea: Not every airplane is meant to be an Oshkosh winner or last forever. Sometimes things can be adequate (acceptable), sometimes they can be better, and sometimes they can be best. As an example, think of tires. They can be had in everything from McCrearys to Michelins. I think over time our readers will even help refine the list. Stay tuned!

![]()

Vic is a Commercial Pilot and CFII with ASMEL/ASES ratings, an A&P, DAR, and EAA Technical Advisor and Flight Counselor. Passionately involved in aviation for over 36 years, he has built nine award-winning aircraft and has logged over 7400 hours in over 65 different kinds of aircraft. Vic had a career in technology as a senior-level executive and volunteers as a Young Eagle pilot and Angel Flight pilot. He also has his own sport aviation business called Base Leg Aviation.