“Airplanes are a monument to human effort,” said Joe Dougherty, a Chicagoland corporate pilot, because building and maintaining them is no easy task. He spoke of all airplanes, not just the Citation X he flies for work or the Bowers Fly Baby he flies for fun. Like several airplanes that preceded it, the Fly Baby was on his bucket list of planes to fly. The plane, which celebrated its golden anniversary in 2012, is a low-cost flier many pilots can afford. “If you can scrape up $8,000, and you have a garage, you can be operating an airplane,” Dougherty said. “There are very few machines like that for the money.”

Affordability was a prime requirement of EAA’s first and only design contest, announced in 1957, seeking easy-to-build, easy-to-fly designs. Entries needed folding wings and the ability to follow the pilot home on a trailer. The Fly Baby, designed by Peter Bowers, a Boeing engineer and founding president of Seattle’s EAA Chapter 26, was one of two airplanes ready for judging at EAA Rockford in 1960. But because neither plane had flown the contest-required time, EAA postponed judging until 1962, when the Fly Baby was first among six entries that included the Turner T-40, Nesmith Cougar and Spezio Tuholer.

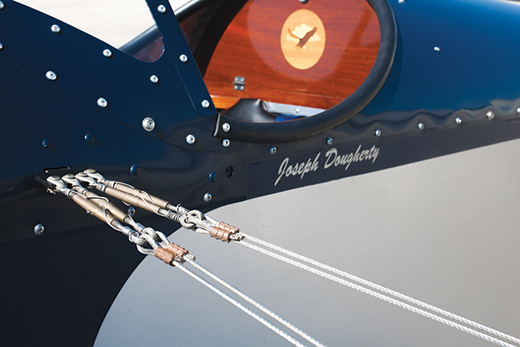

Joe Dougherty and his Bowers Fly Baby.

The prototype’s registration, N500F, represented the number of plans Bowers hoped to sell and the abbreviation for the system that duplicated them. Before he passed away in 2003, shy of his 85th birthday, he’d sold 10 times that number. The prototype was Chapter 26’s club airplane until the mid-1980s. It inspired Ron Wanttaja, whose web site, BowersFlyBaby.com, is the design’s unofficial go-to source for information, advice and digitized 50th anniversary plans ($145, including postage, for both the monoplane and biplane versions).

Dougherty met the Fly Baby through several of Bowers’ 26 books, describing the photo of the author “flying it without any head gear on…it just looked like it would be a really nice flying airplane.” Then he met a colleague of his brother, Gene, a physicist at Fermilab, who’d built two Fly Babys. Worried that a new owner might be injured flying it, the builder dismembered one of them, Dougherty said in somber tones. “I was distressed that a very nice airplane was ruined.”

To more comfortably accommodate his 6-foot-4 frame, Dougherty built heel-wells for his size 13s.

The Fly Baby is not only affordable, it’s accessible. Bowers stood 6 feet, 2 inches tall, so the cockpit accommodates Dougherty’s 6-foot-4 frame. The airplane’s reputation for shedding its wings did not deter him. “Managing risk is a pilot’s preeminent responsibility,” he said, so he read the accident reports (conveniently collected at BowersFlyBaby.com, along with advice for builders, pilots, maintainers and prospective owners).

The NTSB accident reports sort into 23 pilot errors, 12 engine failures, three collisions, 13 wing failures and five “other.” Bowers did not design the Fly Baby for aerobatics, but that’s how six lost their wings. Improperly stored, rotten spar carrythroughs claimed two, and the failure of a corroded turnbuckle and improper repairs after a previous accident got another two. Fatigue cracks in solid flying wires and unequal tension of the stranded-cable landing wires downed two more. Finally, one pilot didn’t put the spar pins in place after unfolding the wings.

Dougherty’s Fly Baby, N922JK, doesn’t have the wing-fold mechanism. He said it’s a very simple design, “a single tube and one bracket with one bolt to hinge on—I could build it in about an hour if I needed it.” The N-number reflects the month and day in 2007 that Dougherty married Kristina Kerwin, an attorney for a global consulting firm. Above it, the “Balsa Flies Better” logo commemorates the models he built that introduced him to aviation. Just behind the Continental C-65, silver letters spell “Certamus Volare,” Latin for “strive to fly,” which defines his life.

Born in Winfield, Illinois, a decade after EAA crowned the Fly Baby its design contest winner at Rockford 1962, Dougherty first flew as a Boy Scout and later learned to fly at Lumanair in Aurora, Illinois. He earned an aviation management degree at Southern Illinois University, then returned to Lumanair as a flight instructor and charter pilot. He started flying corporate after a stint with an air ambulance. He got his first airplane, a Luscombe, in 1994, and traded it for a Cessna 172 in 1996. After five years without an airplane, he bought a Pitts S2E in 2004.

Equal wire tension is an important Fly Baby safety item.

The Pitts was “absolutely a dream to fly,” he said, but it was expensive to own and operate. Enter the Fly Baby (found on www.Barnstormers.com) at Ray Community Airport (57D), outside of Detroit. Dougherty paid $8,500 for the airplane that, disassembled, just fit in a covered snowmobile trailer for the December 2007 road trip to its new home. Dougherty thoroughly inspected, repaired and restored the Fly Baby. Working with Al Heinze, an A&P-IA who supervises and signs off his work, Dougherty logged everything, documenting the practical experience that will one day lead to his A&P ticket. He spent 360 hours working on the Fly Baby before its first flight in June 2008.

The airplane’s fourth owner, Dougherty knows little of the builder who started it 1968, or how far the second builder got before Robert Hunt finished and flew it in August 2004. After logging little more than 75 hours, Hunt sold it for reasons unexplained. What Dougherty does know is that all were careful craftsmen, adept at bonding wood with Aerolite and T-88 adhesives.

The turtledeck baggage compartment.

Reminiscent of the stick-and-tissue Comet models he built as a kid, the Fly Baby uses spruce and fir and plywood instead of balsa. Dacron replaces tissue. Always hangared, the fabric was in excellent condition, which he said was one reason he bought it. Plywood ribs with spruce cap strips ride spruce spars, and a probing visual inspection deemed the 28-foot wingspan fit for flight.

Stringers form the top and bottom of the fabric-covered, semi-monocoque fuselage. Dougherty tap-danced a screwdriver handle over every inch of every glue joint, listening closely for the dull report of debonding. Where he could see the joint, he pressed firmly and tried to separate it. Worming his way into the fuselage, he paid special attention to the aft spar carrythrough and back by the tailwheel, the two areas most susceptible to rot.

Following the safety advice on Wanttaja’s web site, Dougherty upped the landing wires to 5/32, double-swaged both ends. He also angled the landing-gear fitting aft to better accommodate the forces on it.

His search revealed some lightly corroded metal parts and some hardware-store bolts that secured the 16.7-gallon fuel tank to its mounting rails. He replaced them all. Worried that his size 13 shoes hit the fuel tank’s crossbeam support, Dougherty made new floorboards of cherry veneer with 2-inch heel wells. He built a new seat for more comfortable geometry, securing himself with a Hooker Harness. He preserved the bald eagle flying before a Stay-Puft cumulus that Hunt inlaid on the door of the turtledeck baggage compartment.

The Fly Baby paint scheme reflects the original rather than recreating it.

Keeping the airplane true to its era was important. Dougherty built a stock three-panel flat windshield to replace the single piece of curved Lexan secured by a roll-over bow. “If you look at the Fly Baby, the landing gear is the same shape, upside down, as the windshield is right-side up. That’s an important design element to the airplane.” The panel is steam-gauge VFR. Batteries power the Icom A6 handheld transceiver connected to an external antenna. The paint scheme doesn’t duplicate the prototype, but they are related. Dougherty’s wife selected the colors from the Randolph enamel and butyrate dope palettes. “I was thinking royal blue and silver, and she said it needs to be navy,” he said, adding that she was right because the combination draws constant compliments.

Dougherty built a stock three-pane windshield, which mimics the triangular shape formed by the landing-gear struts.

Turning the prop, a friend heard debris crunching in the gears of the old magnetos. Dougherty replaced them with Slick mags, trading in the Bendix cores, with their hard-to-find conical gears. When the new mags’ drive gears missed by an inch, he learned that the 65-hp Continental had a 2-inch-deep -9 accessory case, not the inch-thick case of the A-65-8 listed on the bill of sale. Unable to reclaim his original conical gears, or find replacements, he bought a “dash 8” case, removed the starter gear, and filled its hole with an aluminum plug.

Other Wanttaja mods include a strap under the tailwheel spring, cross-brace on the rudder horn and a tiedown hook for solo hand-propping, which is released from the cockpit.

As Dougherty described it, the Fly Baby is “an exceptionally nice flying airplane with no bad habits. I’ve stalled it left and right, and it spins much steeper than I thought,” he said of the one-time educational exercise of the not-recommended maneuver. The airplane doesn’t have elevator trim (four flights led to a nice mid-range adjustment) or a static system. With the airspeed indicator venting into the open cockpit, the prop blast affects the static pressure: A power-off stall indicates 35 mph, a power-on reads 55 mph, and “climb and approach happens at 60 mph.” By carrying a bit of power to compensate for the wires’ drag, “you can grease seven of 10 landings,” he said. Typically, the Fly Baby gets off the ground in 500 feet and gets back on in 400 feet.

A whiskey compass is the only navigation system. “I thought it was important to have an airplane where you get reacquainted with the wristwatch and the compass and the sectional chart,” Dougherty said. Cruising at 70 mph can lead to uncertain situational awareness, which requires patience. “If a town is 10 miles away, and you’re flying into a breeze, it’s going to be awhile before you can even see which town you’re over.”

After securing its tail, Dougherty props the Fly Baby, which always starts on the third pull.

His longest cross-countries have been to Oshkosh, where in 2008, the Fly Baby earned a Bronze Lindy in the plansbuilt category. If the fit and finish of grand champions is a perfect 10, “my Fly Baby is a solid five or six,” he said of his restoration effort. “It’s an airplane that appealed strongly to the heartstrings of the judges, the romantic appeal of a plansbuilt airplane and a tribute to Pete Bowers.

“Somebody once told me the Fly Baby is an airplane you own for 100 hours, and then you’ll have been there and done that, and then you sell it,” Dougherty said. “And that’s exactly what’s happened.” But he’s found it a good home: the Eagles Mere Air Museum, in north-central Pennsylvania, 70 miles west of Scranton. It joins nearly two dozen golden era aircraft that fly every Sunday, weather permitting, at Merritt Field (4PN7). Many are the last examples still flying, and notable aviators, including Wiley Post, Roscoe Turner and Mary Brush, owned and/or flew several of them.

Four years ago, when his collection got to a size he thought would interest the public, George Merritt Jenkins opened the museum, believing that keeping these airplanes alive matters. “There’s no substitute for seeing and hearing the real thing fly,” Jenkins said. Looking like the 1935 Kinner Sportster B the museum is restoring, the Fly Baby possesses golden era attributes, Jenkins said, and it joins two other homebuilts, a Model A-powered Pietenpol and a Heath Parasol.

At his day job, Joe Dougherty flies the Falcon 7X.

There are two new airplanes in Dougherty’s life. At work, a new three-engine Falcon 7X has replaced the Citation X. And in his hangar is the Fly Baby’s successor, another classic wood homebuilt, the two-seat Volmer VJ-22 amphibian. Dougherty is already rated, and the Volmer’s builder checked him out on land and water before Dougherty flew it home from Florida.

One day, Dougherty plans to build an airplane, but today that task is “a little bit intimidating.” As it does with pilots, confidence comes with supervised experience, so he continues to build his hands-on skill set by sustaining the lives of classic homebuilts, aviation’s often-overlooked affordable fliers.