Rotax owns the Light Sport Aircraft engine market, but the stalwarts are laboring to reclaim lost territory. The 100-horsepower Rotax 912S is a mature design, and the parent company was geared up to deliver engines needed when the finalization of LSA rules jump-started this new sector of general aviation. The 912 series is a substantial player in the Experimental/Amateur-Built segment as well.

Continental and Lycoming strived to create LSA-suitable powerplants from existing designs. Continentals is a carbureted 100-hp O-200D, a slightly reworked version of the O-200A, the first engine installed in the Cessna C-150, which was produced from 1959 to 1977. More than 22,000 O-200-powered 150s and 150 Aerobats were manufactured.

In 1978 Cessna replaced the O-200A with a 110-hp carbureted Lycoming O-235-L2C and called it a C-152. The -L2C engine was replaced by the 108-hp O-235-N2C in 1983. Nearly 7000 152s and 152 Aerobats were delivered before the end of production in 1985. The O-235 was first certified in 1940. Many post-WW-II Piper airframes such as the PA-12 Super Cruiser and the PA-22-108 Colt were powered by this tough little engine.

Many homebuilt designs were created around these two engine families as well, in part because they were so plentiful on the used market and also because they are extremely well proven designs. They are not flawless, but each engines specific weakness is well understood, with many fixes available in the aftermarket.

Continentals O-200D is the firms best bet for LSA acceptance, and has been selected for use in the Cessna SkyCatcher and Zenith Zodiac CH 650.

Weight for It

The 912 makes its 100 hp from relatively small displacement (roughly 83 cubic inches for the 912S, 74 cubic inches for the 80-hp 912) thanks to a prop-speed reduction unit (PSRU) of, typically, 2.43:1. Liquid cooling and the small displacement permit the 5800-rpm maximum engine speed. Capacitive-discharge ignition and altitude-compensating carburetors are standard, and when the 912 was introduced, fairly unusual.

Both of the legacy engines go about things the more traditional way. They are large-displacement engines (201 cu. in. for the O-200 and 233 cu. in. for the IO-233) turning a relatively slow rotating (2750 takeoff rpm for the O-200 and 2400 takeoff rpm for the IO-233) crankshaft thats bolted directly to the propeller.

Earlier iterations of the O-200 and O-235 engines used magnetos to generate and distribute ignition system spark and updraft single-throat carburetor fuel-metering systems.

The legacy engines weigh quite a bit more than the Rotax 912. Where the 912 weighs 125 pounds (claimed) dry, the O-200 is 176, and the IO-233 is around 200 pounds. Airframe accessories such as hoses, mounts and exhaust systems can easily increase the weight of the engine assembly by 50 pounds or more.

The O-200Ds Simple Diet

Changes from previous O-200s include a 14-pound reduction in weight obtained by making changes to the crankshaft and crankshaft flange, the oil-sump assembly, the accessory case and by installing a lightweight alternator and starter.

Mac Little, director of communications and marketing at Continental, says the crankshaft design underwent finite element analysis, allowing TCM to remove 4 to 7 pounds from the crankshaft itself. Its easier to find 16 1-ounce weight reductions than it is to find one 1-pound reduction, Little said. Examples of this philosophy are the cylinder barrel cooling fins. Little cooling is needed at the base of the cylinders, so the fins are tapered toward the mounting flange. There are no provisions for a vacuum pump or a diaphragm-type fuel pump; however, there’s a pad for a spin-on oil filter.

Instead of self-certifying the engine in compliance with ASTM standards, Continental opted to go for full FAA Part 33 certification, which was awarded in October 2008. Part 33 is a modern regulation that requires engines to hit their stated horsepower rating by a factor of +5/-0%. The compression ratio was raised from 7.0:1 in the A-, B- and C-series engines (certified under the less exacting requirements of CAR 3) to 8.5:1 in the O-200-D to comply with this requirement.

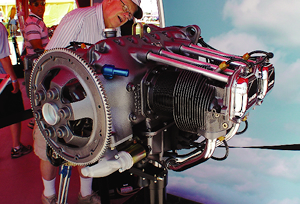

The IO-233 is an aggressively pared-down version of the O-235 with electronic ignition and a lightened accessory case. Note the tapered fins on the cylinder barrels; these shave precious pounds.

Lycoming Joins the Fight

Lycoming introduced its IO-233 at AirVenture in 2008. Don’t let the numerology fool you: The O-235 was actually a 233-cubic-inch engine, so the displacement hasnt been reduced for the new powerplant. Considered sturdy, the O-235s big shortcoming in this battle is weight, and that was among the major goals for developing the IO-233.

Lycoming busted out with new technology early in the 21st century by actively developing and testing new reciprocating engine technology at its facility in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, prior to moving these efforts into the adjacent Advanced Technology Center and Advanced Solutions Center (ASC), which was dedicated in 2005.

Lycomings IO-233 engine is rated for maximum continuous power outputs of 116 hp at 2800 rpm and 100 hp at 2400 rpm. It can produce rated power burning (and will be certified for) 100LL fuel or Lycoming approved 91/96 UL (unleaded) fuels. Advertising copy states that the fuel consumption numbers are 5.25 gph at 75% power and 4.5 gph at 65% power.

The O-235-L2C used in the C-152 tipped the scales at 249 pounds. Lycoming says it hasnt messed with the power-producing core of the engine, which is partly why the TBO remains at 2400 hours. Thats 400 more than the O-200 series engines and 900 more than the Rotax 912.

Lycoming trimmed nearly 40 pounds off the weight of the O-235 by stripping off everything that was not needed, according to Mike Kraft, VP of engineering. The most obvious visual evidence of the weight-loss program is the accessory section of the engine. There is one pad for the E-Mag ignition system and a pad for a spin-on oil filter. Thats it. Standard equipment includes roller tappets, a lightweight starter and alternator, and a throttle body fuel-injection system.

The single-drive E-Mag system contains two autonomous ignition units and a miniaturized three-phase brushless alternator in a single housing. The alternator provides ignition power if there’s a loss of aircraft electrical power. The E-Mag, which developers Brad Dement and Tom Carlson say was designed from the ground up as a modern replacement for light airplane magnetos, automatically varies the spark timing from 20 before top dead center (BTDC) at idle to 39 at cruise rpm by reference to a fixed map that determines the correct firing angle by sampling engine rpm and manifold pressure. In an interview, Dement said the variable timing feature reduces fuel consumption by a gallon to a gallon and a half an hour at cruise rpm.

The I in engine prefix part numbers signifies that the engine is fuel-injected. Lycoming is calling the fuel-metering system on the IO-233 a throttle body fuel injection system. Unlike other GA fuel-injection systems, the Lycoming throttle-body system does not inject pressurized fuel to the cylinders via fuel-injection nozzles. Advantages of throttle-body systems include a lower parts count than the traditional carburetors, an increase in full power output because the system does not have a restrictive butterfly-type throttle valve, and a drastic reduction in the possibility of carburetor icing.

Continentals O-200D LSA engine isn’t much different from its older brethren, but thats OK. The systems are time-proven, familiar and dependable if the ignition (plug fouling and repetitive 500 internal magneto inspections) and fuel system (carb ice) shortcomings are recognized and anticipated.

The IO-233 is different from its elder in that the two systems with known liabilities-ignition and fuel-metering-are updated. But the engine also lacks the thousands of hours of field experience.

So whats the upshot for the Experimental builder? Continental does not yet have a dedicated lineup of engines for homebuilders and sells only through approved kit manufacturers and, prominently, Mattituck Aviation Services (itself a subsidiary of Continental). Lycoming continues to ramp up its Thunderbolt series of engines, and while the IO-233 was not, at press time, on the list of available T-Bolt engines, its a reasonable expectation that it will be one day.

![]()

Steve Ells is what you call a gen-u-ine mechanic, a bonafide A&P with an Inspection Authorization. Former West Coast editor for AOPA Pilot and tech guy for the Cessna Pilots Association, Ells has flown and wrenched on a wide range of aircraft. He owns and wrenches (a lot!) on a classic Piper Comanche. But don’t hold that against him.