Like some sort of verbal restricted area, certain subjects are such tropes in aviation scribbling that I steer around them like they were cumulonimbus. But sometimes the risk of not saying anything is too high to ignore, and it seems now might be one of those moments. While you could justifiably predict I’m going to ramble on about fuel cost or bans, I’m going even more basic: noise.

Disturbing the peace has probably been an aviation issue since before Orville and Wilbur, as Sir Hiram Maxim’s flying ditty weighed nearly four tons, boasted two 180-hp steam engines and 18-foot propellers. It had to have huffed and chuffed annoyingly to the neighbors even in the 1890s, but Hiram had a really big yard so noise complaints aren’t what we remember him for. He had other inventions more worthy of complaint, regarding not only noise but some of their other effects, especially if you were on their receiving end.

But again, Maxim was a stretch ago and we’ve moved on as the cliche goes. In the noise department that means the admittedly glorious but eventually tiresome roar of four 3000-hp supercharged radial engines taking off over your bungalow has come and gone, along with the head-splitting shriek of low-bypass turbojets. Today we have amazingly hushed high-bypass turbofans whisking the sullen legions to and fro, but as my brother who lives under the departure end of a major airport can attest, even these miracles of sound suppression don’t quite cut it on a daily basis.

Then there are us, we happy few, sallying forth above our neighbors 180 barking horsepower at a time. Nearly steampunk in our attachment to rivets and open exhaust, we’ve got propellers whapping at the air and flight characteristics destined to keep us bleating overhead interminably. Think of the flight school’s doggy old 172 clattering around the pattern ad nauseam or Joe Plaid snarling off to lunch in his open-exhaust homebuilt. Even a saint would be forgiven for googling what FLAK stands for.

It’s worth acknowledging at this point that little airplane noise—just as smoking cinders from steam locomotives and manure in the streets—was once tolerated but not so anymore. The world population has doubled since I was a schoolboy and we’re all living on top of each other. In short, there’s more noise everywhere and people are tired of it.

But it’s much worse than simple proximity. Technological change moving faster than humans can evolve means attitudes have hardened since the prevalence of tricycle landing gear. In a society gone mad, any intrusion—including noise—has become personal, and while I don’t want to be the one telling you, no one likes you or your flying machine. Where once chances were fair you might have been admired for being a pilot, or at least for building your own plane or even just for being outside doing something, today you are not liked. As in despised for mindlessly flaunting your disdain for climate change, your disregard for the underserved, your flippant consumption of fossil fuel, your disdain over the horrors of lead poisoning, your disgusting embrace of elitism. In a recent photo op regarding outlawing 100LL in two years, a California legislator linked private aviation to environmental injustice. Other quotes from the event are, “The drastic effects of this toxic fuel are evident all around us,” “We deserve a clean, healthy environment where our children can thrive, not one where their well-being is sacrificed for someone’s personal hobby” and “There are three airports within a 10-mile radius and that’s just not OK.” Make no mistake, a meaningful percentage—a minority today, but a measurable and likely growing number of people—have no use for the very idea of private aviation. Your clinging devotion to the idea of just anyone flying over the rest of us is both frightening and abhorrent. Bragging about it at wide-open throttle with the prop set on fine pitch is becoming a middle finger to oppressed masses. Or so the narrative has become.

This may sound delusional in the Midwest, but in the cauldrons of unrest that are our cities it is depressingly true. The whys are beyond this short column, but the timeworn challengers are happy to stoke the pressure. The building barons salivate over another airport driven to extinction no matter what the excuse. Local politicians are too happy to bring in the greater tax revenue from such “underutilized” real estate. The casual citizen doesn’t mind having the noise go away. The timid are happy those dangerous planes won’t be crashing into their house and stopping the rain of lead justifies any action. If privileged nutcases still want to fly they can go somewhere else farther away.

It doesn’t matter if our detractors have lost touch with reality or not. They are present and joining forces with environmentalists, developers, politicians and anti-capitalists. Out on the coasts they’ve become a factor. We two-hundredths of the population aren’t going to change many minds, at least not quickly, but in the meantime we could make less noise. Out of hearing, out of mind as it were. It’s that or die the bureaucratic death.

As Experimental aviators there are three opportunities to mitigate our aural footprint. We can incorporate noise abatement—at least some acknowledgment of it—into the hardware of our planes during construction. We can take action as pilots in command. And we can participate in the political and community outreach domains—such as fly some Young Eagles and write a few letters.

While the majority of objectionable airplane noise is propeller generated, there are few practical alternatives to the props now available although taking the huge financial jump to a constant-speed prop should prove meaningfully quieter. In any event quieter props would seem a worthy goal of our commercial patrons.

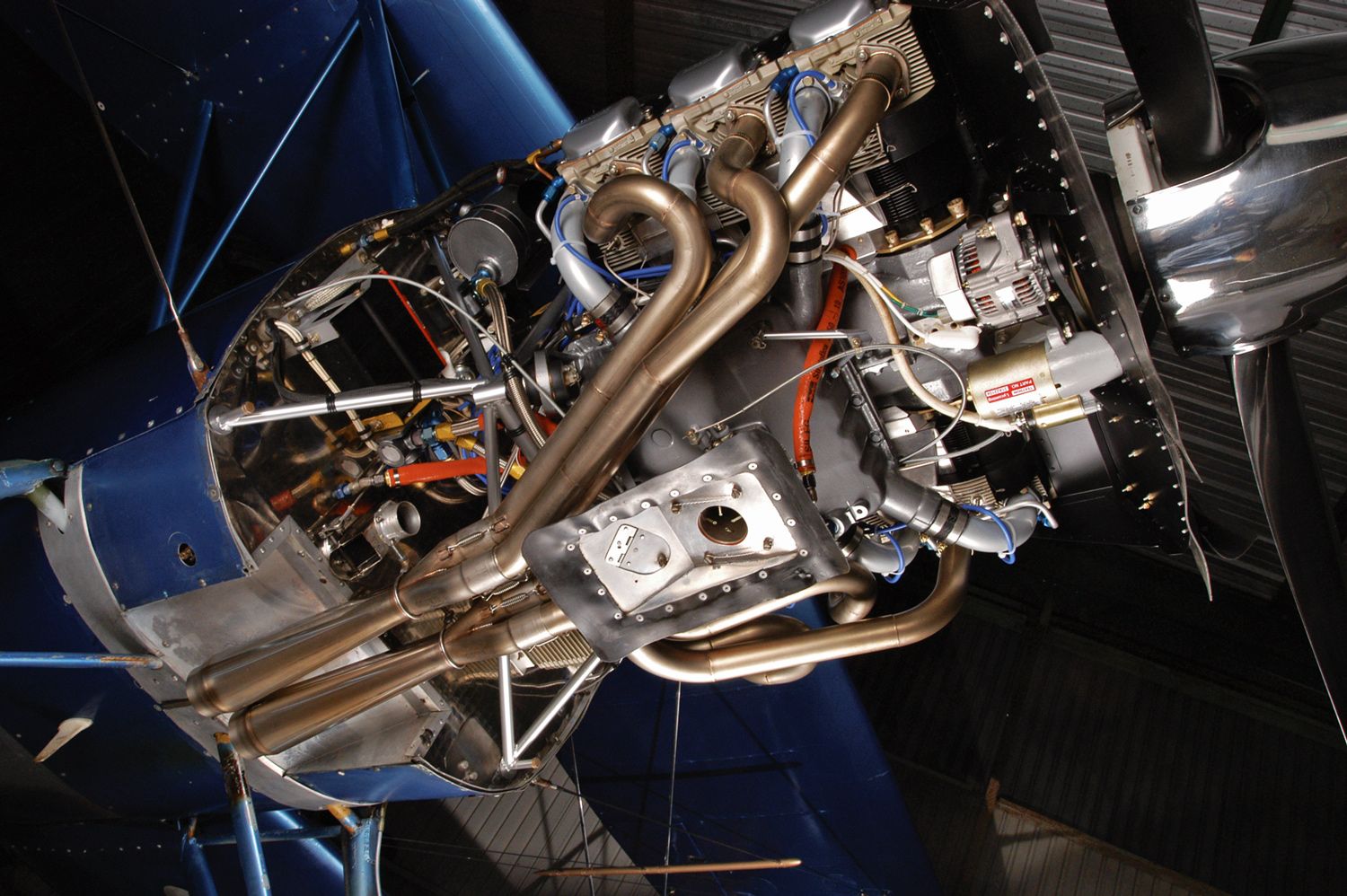

Engine exhaust noise is more under our control as builders. Short individual stacks can be effective for power, but are both hideously loud and in a raspy, unpleasant way. Consider admittedly more expensive (and weightier) crossover or collected (four-into-one, six-into-two) exhaust systems. They are far quieter, especially when designed for the correct length, and offer superior torque plus heat cuff possibilities. We could consider mufflers, but they are a difficult technical issue on most current airframe/engine combinations. Still, it’s something for us to individually and collectively consider.

Or let me offer my favorite building solution: Construct a fast, high-power airplane that even at not quite full chat gets up and away in a hurry. Good for everybody.

On the piloting side limiting propeller rpm and moving the loud lever the other way when nearer the ground-bound can definitely help. It all depends as there are so many variables. My home field has a vast, nearly unpopulated military base on one side and my hometown on the other. I make a small heading change to favor the military base on the upwind to the point where I might have inadvertently dragged a wingtip through their restricted area, and when turning crosswind over the houses I make a power reduction, even in slow-climbing, small-engine puddle jumpers such as our C-140A. A corresponding lowering of the nose keeps the speed up and enough of a climb going, but with definitely less racket. It’s sufficient to get me around the pattern for landing practice or away from the airport with minimal delay before powering up and heading out of Dodge. Your airport may not offer such obvious options, but ground tracks are something to study and work with.

When you fly is another mitigation. We’re all busy and often are lucky just to have any time to get in the air, but if you have a choice it’s smart to avoid early mornings, especially Sundays. Or at least avoid pattern work at those times.

The other operational issue is the blue knob, should your fly buggy have such a control. Some propellers are incredibly loud, but pulling back the rpm helps immensely. In my fast-climbing Starduster, I use it all for takeoff and initial climb (just seconds to pattern altitude), but then pull back to 2300 rpm and maybe 20 inches to cruise climb away from the ground before returning to full throttle if going high.

Above all, avoid burying the prop knob against the instrument panel when 10 miles out for landing. I’ve seen guys do it; their explanation is they don’t want to forget to put the prop in prior to landing, so they do so one zip code out from the airport and get it over with… and I feel like kicking them out the door. Driving around at low altitude with the prop in high pitch, especially with the gear and flaps hanging out, is a hanging offense. I can’t think of a more useless way of closing an airport.

Enough with my noise. Just remember—everyone on the ground is listening and increasingly getting ideas.

Hi Tom,

I’m a new pilot this year and only just closed on my Flight Design CTSW a week ago. I’m glad I have come across your article so early in my flying career. I’ll definitely be keeping my neighbors in mind as I fly. Thank you for your thoughtful words!

Cheers,

Wayne

As a kid, born in 1943, that grew up with a surviving World War 2 combat pilot, who flew most of his life, I have loved airplanes all of mine. Have ridden in a lot, in the Army and including civilian aircraft but never got my pilots license. Anyway, I love aircraft, especially small lightweight private aircraft. I just found this site.. I really enjoy your humorous, witty choise of words, on this important topic. Thanks again!!!