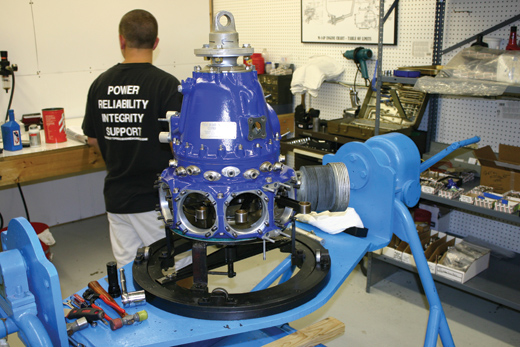

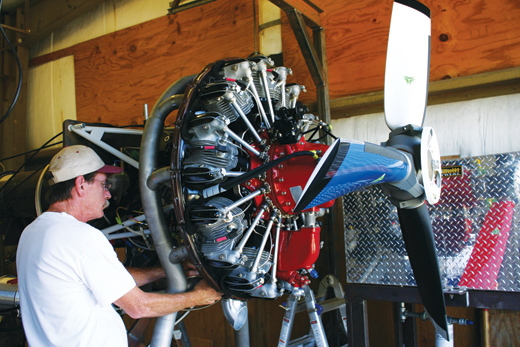

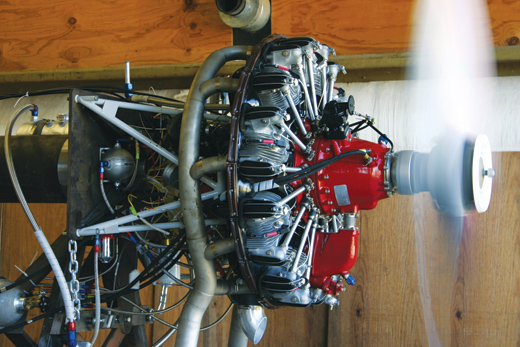

A Barrett-overhauled Vedeneyev looks just right on the front of a Waco. The 360- to 420-hp, nine-cylinder radial is popular in a variety of airframes, including the Pitts homebuilt.

The growth and detail development of the radial engine during WW-II was nothing short of phenomenal. In a few short years, the radial gained power and reliability, and it looked set to be the motivator of all things large and wing-y. And then came the jets. While the turbine engine killed the big radials for use in military and civilian aircraft after the war, the big round engines would persevere in utility roles.

A surprise to many, the radial remains an important gap filler. Most small turbines start at 400 shaft horsepower and go up from there—way up, actually—but have neither low cost nor great fuel efficiency in their favor. Familiar flat, opposed-cylinder engines top out at 350 hp for most applications, though there are a few exceptions. (The 425-hp, geared, turbocharged Continental GTSIO-520, as used in the Cessna 421, is an example, as is the rare eight-cylinder Lycoming IO-720.) So there’s still a need for an engine in the high-300s to low-400-hp range.

An M14P undergoing overhaul at the Barrett facility in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The geared reduction drive is incredibly robust, says Monty Barrett, as long as it’s assembled properly during overhaul.

Into the Gap

Slotting right in is the Vedeneyev M14P, a nine-cylinder, air-cooled engine with an interesting ancestry. It began life at the Ivchenko Design Bureau in the Ukraine during the 1950s as the AI-14, but after a consolidation of Russian aerospace, it landed under the control of Ivan Vedeneyev. There it was developed for aircraft and fixed-base operations (driving generators). In its various guises, the M14P has been used in aircraft as diverse as the gawky PZL Wilga and the stunningly beautiful Pitts Model 12. As you would expect, the M14P provides impressive power—nominally 360 hp but as much as 420 in certain variations.

Production ceased in 1989, but there are many running engines and a wide range of cores available. In the last 10 years, Monty Barrett, paterfamilias of Barrett Precision Engines, has continued to collect good cores and conduct a profitable niche business bringing these engines back to like-new condition. The business started as simple rebuilds, but as his familiarity with the engine grew, he started to see ways to improve it, both from the standpoint of improving known flaws (more accurately, compromises) and freeing owners from the yoke of rare, outdated accessories.

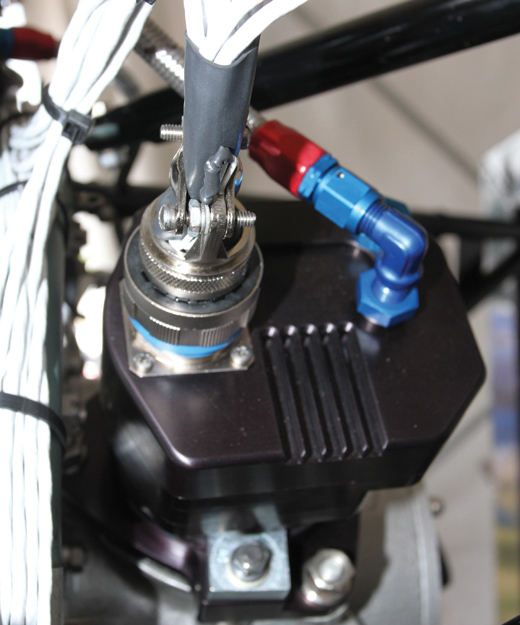

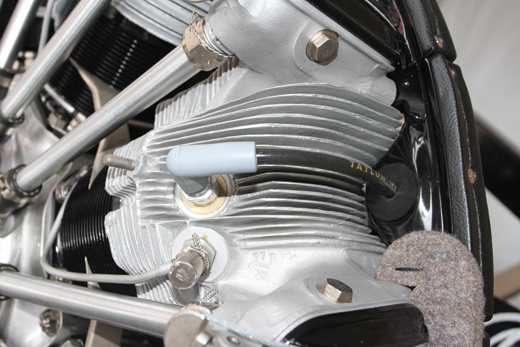

Barrett’s electronic ignition bolts straight to the M14P’s magneto sockets (above). A heavy-duty wiring harness sends trigger signals to the coils (below), which are mounted near the cylinders they serve. Automotive plugs (right) are part of the package. Incidentally, the silver barrel visible below the spark plug is part of the M14P’s air-start system; it does not use a conventional electric starter.

Slug Fest

“These are really great engines,” says Barrett, who should know. He’s seen the insides of many, has visited the Ukraine to talk with the original engineers, and can claim to have a thorough backdrop of aero- and auto-engine experience to offer as a comparison. “They’re extremely well built in the ways that matter,” he says, pointing out that while the external surfaces might lack the polish of American engines, all the important aspects are there. “The machining in these engines is very good,” he says, “especially the gear train.” He maintains that the Ukrainian designers and manufacturers concentrated on what made the engine work, not what made it pretty.

But there were inherent limitations in the engine that stem largely from the design compromises intended to suit the M14P for harsh life in Russia and elsewhere. In addition, because the engine was meant to run on particularly low-grade fuel, the standard compression ratio was a mere 6.3:1, low by flat-engine standards, but in line with other radials. What’s more, the pistons used an antiquated five-ring design. Barrett felt the engine could probably benefit from slightly more compression and definitely from a more modern ring pack.

Barrett’s forged M14P pistons bring the compression ratio up to 7.75:1, but, more importantly, they use a much more modern ring set that reduces oil consumption from a typical 1 quart in 1 to 2 hours to 1 quart in 10. “This has benefits for power and for keeping the engine cleaner inside,” Barrett says. The pistons are intentionally the same weight as the originals to preserve balance factors. “When we supply pistons for overhauls taking place elsewhere, we ask the overhauler to give us the weight of each piston assembly, and we match that. We do the same in house…matching the weight of the piston assemblies that came out.”

A top overhaul, including the new pistons and honing of the cylinders, typically runs $7800. A complete overhaul including the new pistons runs about $23,000.

Barrett developed a new spray nozzle for the Airflow Performance fuel-injection system, which replaces the automatic carburetor most often found on the M14P.

Fuel Delivery

Standard on the M14P is a Russian-designed carburetor breathing into the supercharger inlet port, a fairly normal arrangement for a mid-size radial. (The M14P displaces 644 cubic inches.) But the carburetor is difficult to set up and hard to get parts for. In response, Airflow Performance developed an injection system using its Bendix-style throttle-body/controller and single fuel injector housed in a spacer between the throttle body and the supercharger inlet. In this way, the system became a single-point injection system, mainly because there’s no simple way to install the injectors at or near each cylinder’s intake port. (And with the supercharger doing double duty increasing manifold pressure and acting like a 100LL-drenched Cuisinart to help atomize the fuel-air mixture, you wouldn’t necessarily want to put the injectors at the ports.)

The Airflow Performance setup worked dramatically better than the original carburetor, according to Barrett, but wasn’t yet perfect. He noticed that during certain power conditions, the No. 6 cylinder would fall out of group. That is, its exhaust-gas temperatures would drop, indicating a locally rich mixture. Barrett felt the injector wasn’t atomizing the fuel as well as it could, and so droplets of fuel were falling out of suspension. To test his theory, he tried new fuel nozzles with varying sizes and numbers of orifices until he landed on one with 48 holes. On his dyno, this one change resulted in a 100-pound increase in static thrust, or about 10 hp. Moreover, the mixture distribution came together. “We can run this engine to 50° F lean of peak [EGT], and it’s still very smooth. That takes the 50% cruise fuel flow from 15.5 gph to 12.2, and we get a 40° F drop in cylinder-head temps as well.”

The complete fuel-injection upgrade including boost pump runs $5300.

Allen Barrett prepares an M14P for a run on the company’s test stand. This highly instrumented setup can look deep into the M14P’s soul, and it was critical to the development of the injector nozzle and ignition system.

Sparks to Go

The final piece of the puzzle was a new ignition system to replace the M14P’s outmoded magnetos, parts for which have become increasingly hard to find. Introduced at Oshkosh last year and promoted at Sun ‘n Fun this year as ready to go, the ignition is a relatively conservative design. It starts with two integrated modules that bolt to the engine where the magnetos usually reside. Inside are the analog circuits to run the system, as well as a permanent-magnet alternator for power backup.

In normal mode, the system runs on ship’s power. But should that power drop offline, the internal sources will take over without a hitch, according to the company. “It was designed so that a complete power failure in the airplane won’t mean anything to the engine,” Barrett says.

While the system is simple, it isn’t dumb. “It’s fully bolt-on,” Allen Barrett (Monty’s son) told me at Lakeland this year, “and has an automatic start function that fires the plugs at top-dead center until the engine reaches 500 rpm; then it ramps up to the running advance.” Monty Barrett explains the timing-advance philosophy. “I wanted to avoid having a lot of [ignition] advance at idle to keep the temps down. I also wanted to keep the maximum advance reasonable so we wouldn’t run into detonation issues.” As a result, the three-dimensional advance curve looks like a field with a tent in it—that is, maximum advance occurs at 27 inches of manifold pressure and 1700 engine rpm, a typical cruise setting. There’s less ignition advance above and below that power point. Not only are these new “electronic mags” more efficient and capable than the Russian devices, they’re 20 pounds lighter overall; that’s for the full set and includes removal of the “shower of sparks” starting system needed with the original mags. Finally, Barrett acknowledges that the hardware developed for the M14P could easily be transferred to flat engines. “We’re going to do it,” he says, “but we want to take our time and carefully map the other engines.”

For the M14P, the system, together with the latest pistons and injection nozzle, resulted in one engine producing 400 hp (corrected) on Barrett’s dyno—and that’s an otherwise standard M14P, typically rated at 360 hp.

Barrett sells the ignition system for $7700 complete. At a time when a new 300-hp, six-cylinder engine is crowding $60,000, the M14P looks like a great deal. A complete overhaul including these new products runs $36,000, while an engine purchased outright costs $46,000. That’s not bad to get 360 hp onto the front of your project—especially when you consider that the Vedeneyev is cranking out this power with relative ease and sounding great in the bargain. Long live the radial!

For more information, contact Barrett Precision Engines at 918/835-1089.

Hello!

How can I buy ignition for m-14?