Before the 1970s there really weren’t any kit aircraft. There were lots of homebuilts constructed from plans, and Aircraft Spruce (among others) was turning out materials packages for popular designs—but they were just that—packages of raw materials that approximated what you needed to fabricate parts for a particular set of drawings. Hardware was rarely (if ever) included, and while there were custom houses producing a few engine mounts and the like, you were just as likely to receive a few lengths of the appropriate sized 4130 steel tubing as you were something that looked like you could hang an engine on it.

I have seen numerous claims as to who produced the first complete aircraft kit, and I am not going to try and adjudicate as to who actually deserves the honors, but in the early 1970s a few such kits began to appear. Even then, the word “complete” had different meanings to different people. At least one manufacturer taped a razor blade to the outside of the box, so that the new owner had the appropriate tool at hand with which to open the boxes—now that is complete. Except…things that might sit awhile, like paint or primer, still needed to be purchased. Very few kits include all of the fluids you’ll need, and there is significant debate over the inclusion of assembly lubricants—are they a “tool” or part of the airplane?

All kidding aside, builders today have a wide variety of kits to choose from, and it pays to look into the particular company’s definition of completeness. You can still purchase plans and raw materials—many such offerings can be found in the back pages of this magazine, produced by small companies and offered with little more than moral support, experience on the end of a phone, and (honest) best wishes for your build. If you choose to go this way, and this is your first build, we’d suggest that you find an experienced builder nearby, and add them to your circle of friends. Airplane construction is full of specialized techniques and methods that, while not always difficult, aren’t always intuitive.

Finding all of the necessary materials to go along with your plans can also be a struggle. It is important to realize that very, very few airplanes can be built safely using hardware store materials and parts. You’ll want to quickly bulk up your catalog collection with names like Aircraft Spruce, Wicks, B&B Aircraft Supplies, and others too numerous to mention. Haunt the fly markets at Sun ‘n Fun and Oshkosh, of course—but beware of parts that have been around since the Great War. There might be some degradation of insulation or flexibility.

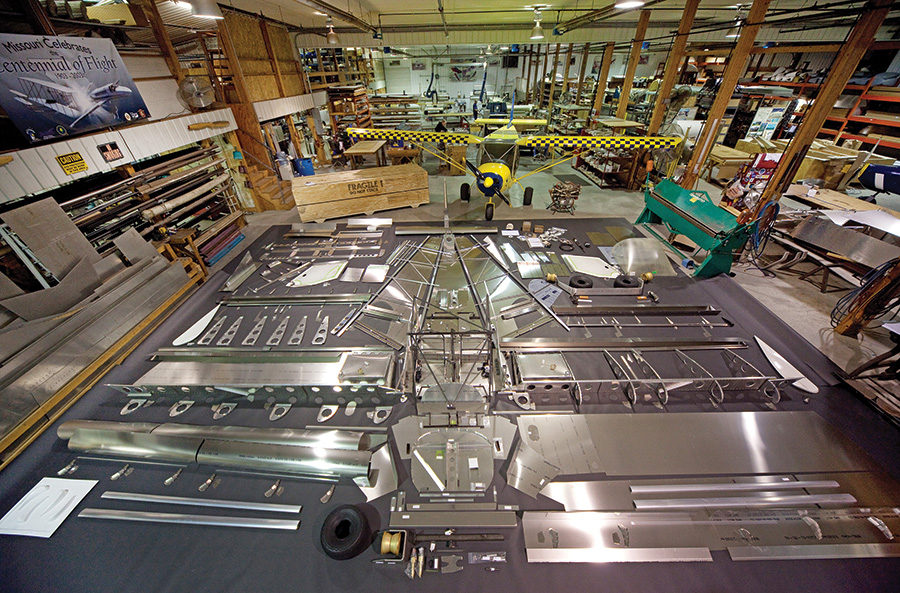

The kit for the Zenith STOL CH 750 includes virtually everything you need to build the airframe. (Photo: Courtesy of Zenith Aircraft Company)

A Closer Look at Kits

Let’s take a step up from plans and look at kits. Yes, there are kits that really require very little fabrication—and the instructions are very much a matter of inserting Tab A into Slot A—or at least they seem like that to someone who has built from scratch. Late-model designs from the big names are often like this, and the instructions will hold your hand from start to finish. Not long ago, the kits from Van’s Aircraft started out in excruciating detail when it came to building the tail pieces (the first part of the job). They almost told you which hand to use to pick up the part before attaching it to another part.

But as the process of building the airplane went along, Van’s assumed that you had learned the various methods of construction, and before you knew it, you were in final assembly, and the step says, “Install the wing.” Well, not literally—but indeed, there was much less detail as you went along. The latest offerings from the same company, however, maintain a level of detail throughout, from start to finish. There are builders who have completed fine aircraft who, before they started, had barely changed the oil in their cars. Remember—this is about education—and it shows.

Many of the companies that you find listed in these pages offer very complete kits. But most still require you to buy your own paint, fluids, battery, and upholstery. Frankly, this is good for the builder because paint dries out—and many have their own ideas on what they want for the interior. There are kits that come with complete avionics packages, and builder forums are full of comments that indicate that builders would rather have this, or that, instead—so it’s a no-win problem for the kit company.

Some kit companies have chosen an interesting middle-of-the-road stance on completeness. Sonex, for instance, offers complete kits with pre-punched parts and matched-hole construction, yet they leave out most of the standard hardware you need to complete the project. They provide plenty of rivets, but no nuts or bolts. Why? Because of financial efficiency. Instead of keeping a huge variety of aircraft-grade hardware in stock (an expensive prospect for any small business), they provide a complete list of hardware needed for each kit to companies that do have a complete inventory of such hardware—like Aircraft Spruce or Wicks. The builder goes to these suppliers who can provide a complete hardware package based on Sonex’s list. Since Sonex tells the customer up front in their cost estimator how much the hardware will cost, there is no misrepresentation here. It is efficient for everyone involved, since a large company can use their economies of scale to provide the hardware at a lower cost than the smaller company can.

The Cassutt wing and tail kit includes these welded structures, but not much else. You’ll need covering material and other items to convert these frames into usable parts. (Photo: Paul Dye)

What’s Not Included?

Many plans and kits have traditionally stopped at the firewall, with little more than a suggestion to “Hang the engine here, and build a cowl around it.” Take a look at a complete set of plans and what the kit offers in the way of firewall-forward instructions and materials. If you have been working on airplanes much of your life, you can probably gin up what you need pretty easily. If the extent of your experience with aircraft powerplants is to check the dipstick to see that there’s oil, you might want to reconsider certain kits—or at least find a buddy that knows their way around a Lycoming or Continental to help out when it comes time.

Regardless of the level of completeness, expect that you, as a builder, will be doing some purchasing. Even if that kit company provides the oil for the engine, you’ll be finding things that you want to change or upgrade. Buying avionics when you open the first big boxes is probably not a great idea anyway. The radios could easily be obsolete before you plug them in for the first time, and warranties often are based on purchase date—not the date the equipment is put into use.

The best thing you can do when shopping for an airplane is to research the level of completeness. Ask those who are already building how many times they order extra parts each month—or week. Get an idea what you are in for. There is no right or wrong here—just differences in philosophy (and capability) between manufacturers as to what will work best for them and their customers. Remember, it’s important to be comfortable with your kit company’s style of business because you are going to be married to them for as long as you are building and flying their aircraft. Get comfortable with whatever you choose—and then build on!