We know that most of you are hard-nosed, “show me the numbers” types who value an objective assessment and accurate descriptions over fluff and circumstance. And we love you for it.

But we also recognize that the beauty of flight is something positively magical. To capture it on film—or, more accurately these days, as a pile of ones and zeroes—is a special thing, not easily accomplished. Here at KITPLANES®, we put a surprising amount of effort into gathering compelling images for your enjoyment, and it’s not the work of a moment. Because we are often asked how we get the magic to hold still long enough to put it on the page, we thought we’d bring you along on a photo shoot to show you just how it’s done.

Man, Then Machine

The first priority for us on a photo assignment is to determine that we have qualified formation pilots. All of the work we do requires two aircraft to fly relatively close to one another, stabilized in cruise flight, so safety is absolutely the first priority. Sometimes the pilot in the airplane to be photographed has military experience—usually a good sign—and that gets us a leg up in the vetting process. Regardless, actual formation experience is absolutely essential. Teaching yourself formation flying is bad business, doubly so during a photo shoot.

As a safety precaution, I keep a long list of excuses at the ready in case it becomes obvious that the guy flying the following airplane isn’t up to the task. Cameras jam, CHTs skyrocket…anything can happen on assignment. Our belief is that it’s better to try a second time with a different crew than to push on when it’s clear something isn’t working. In our business, we don’t have the option of flying a “mock” mission before the actual photography, but it’s something I recommend among weekend-flying friends just to be sure all of the sticks are up to the job. Safety first, ego last.

Autumn colors can make a shot work even when the light fails to cooperate.

A Mountain of Variables

With the personnel elected, the next step is to arrange both the subject and camera aircraft. It’s harder than you think. First, the two aircraft need to be reasonably close in performance because the best images are captured when the ships are side-by-side with little to no relative movement. The idea of a 50-knot-faster airplane just “flying by” doesn’t cut it in the world of pro photographers. (Besides being dangerous, the poor photographer has little opportunity to frame and capture the shot.)

So we need two aircraft that can hang together in cruise flight. Sometimes this puts one airplane at the extreme of its performance envelope. I recall having to fly my GlaStar Sportsman at 60 knots indicated to keep pace with the Breezy we shot in 2009; that required dropping a notch of flaps and paying close attention to both power and the slip/skid ball. The Breezy pilot was fairly cobbing it to stay alongside.

A slow subject aircraft presents less of a problem than a fast one. When the airplane being photographed is significantly faster than the camera platform, it must slow to the lower portion of its performance range to stay on station. This usually results in a nose-up pitch attitude that can look dynamic when captured by a true pro, but causes problems for the rest of us, and can even complicate framing for the photographer when the natural horizon slips into the shot. Worst of all is when the subject aircraft has to drop flaps to remain safe. When there’s no other option, you can always climb to altitude and run the shoot downhill, giving the lead (platform) aircraft a fighting chance.

Don’t be afraid of letting the background become an important part of the photograph. The Murphy (above) was photographed near Chilliwack, British Columbia; the Velocity (below) over Avalon, California.

Glass Ceiling

When you look at a professional image next to one you might have captured from your own airplane, you may notice how much sharper the professional images are, and how much more saturated their colors. There’s one very good reason for this: We don’t shoot through windows. Ever. Well, almost never. High-end photographers often lease a special B-25 bomber with an optically perfect nose bowl (and other apertures) that allows the Canon-hauling set to stay warm and get the ideal shot.

For us, it’s all open doors and windows, which creates something of a problem finding the best platform. My Sportsman was equipped with a third door on the left side that we removed for air-to-air photography. (Naturally, I did a substantial amount of flight-testing, including a lot of slow flight and cross-controlled stalls, to be sure the open door didn’t create any odd handling characteristics. The worst artifact was a nasty booming sound that appeared only below 65 knots with the flaps extended. Eventually, I determined that a vortex from the inboard side of the flap, which was just outside the opening, was coming into the cabin and smacking the bulkhead cover sealing off the tail cone.) Just inside that open door, the photographer could slide backward and aim the camera at the following airplane. We have also used the Sportsman with one of the front doors removed, but it can be difficult to twist around in the seat to capture the trailing aircraft.

Photographers love the Beech A36 Bonanza (and its fuselogical twin, the B58 Baron), the Piper Cherokee Six/Saratoga, and any aircraft that was once a jump plane with a removable door. We have also made various single-engine Cessnas work: The 172 and 182 are passable platforms with the copilot’s window open, but the 210 requires a bracket to keep the window open in flight.

Regardless of the aircraft used, we always have a preflight briefing with both pilots and photographer. In this session, we’ll discuss the direction of the flight, the approximate altitudes and the air-to-air frequency we’ll use. We also discuss escape strategies. For example, should we encounter traffic during the shoot, it’s stated and understood that the airplane up and to the right will always break to the right and climb; the opposite would be true for the following aircraft. We also discuss the word or words to be used to initiate a break and reinforce for the pilot of the lead aircraft that he’s solely responsible for maintaining terrain and airspace clearance as well as looking for traffic. In fact, the role of the platform pilot is just as vital as that of the other stick—he needs to be smooth, aware of his surroundings and prepared to call off the shoot at the first sign of trouble.

For the pilot in the subject aircraft, there’s just one job: Remain safely in position relative to the camera platform. Period. No looking around, no fiddling with the GPS. Watch and respond to the other airplane. That’s it. For some high-performance aircraft whose engines are fussy, I like to have another pilot aboard the subject ship whose sole job is to keep the engine happy, switch tanks, watch the gauges. If I’m the pilot of the subject airplane, I’m not looking inside much, if at all.

The classic air-to-air image: strong sunlight, a high-contrast background and an impressive prop disk.

Reflected Glory

Obviously there’s more to stunning aerial photography than getting two airplanes up at the same time. Most critical is the light. We do our best to shoot only in the “golden hour.” That is the time between sunrise and one hour after, or an hour before sunset until dark. Typically, the light is just nicer during sunset sessions, with a more textured golden hue that we generally prefer, though sunrise missions also usually benefit from smoother air. Morning or afternoon, you need the combination of the two—good light and smooth air. If you want good results, don’t even launch unless you have both. If we’re on site with anything more than a very thin high-level overcast, we won’t go. Hard overcast is great for shooting interiors but renders air-to-air images flat and lifeless.

Why do we love sunset shooting? First of all, the angle of the sun makes the image more dramatic, all else being equal. A low sun angle gives you the opportunity to have the airplane lighted and some of the background dark, an effective tactic with white aircraft, and you will also get some depth to the background. During this pre-sunset time, hills or mountains behind the aircraft will remain lighted as the valleys below them become dark, offering a bit of texture.

If you have pilots capable of switching leads, flying the camera ship on the subject can make for interesting angles. Here, the sun is just about to fully set, as evidenced by the light on the airplane but darkness on the ground beneath it.

We do very little shooting in a straight line. For the most part, we find open airspace with a clean background and in clear light, and then perform 360° turns until the photographer says stop, or one of us gets a cramp in the neck. We also alternate “step down” and “step up” formations. With the subject airplane stepped up, it’ll be at or above the horizon, with just the sky or clouds as the background. Stepping it down shows the ground and can be quite dramatic at the right time of day. We also ask the pilot of the subject aircraft to move around relative to the platform, taking him out toward the wingtip or back toward the tail, all over the place. The limiting factors here are the following pilot’s ability to see the lead aircraft and the photographer’s ability to get the subject in frame without parts of his airplane interfering. Some platforms give you more flexibility than others; you can see why serious photographers don’t like to shoot out of storm windows.

Lying down on the job, right? Not exactly. Here, Belvoir Media’s multi-talented Paul Bertorelli risks grass stains and bug bites to get just the right angle.

Camera Basics

We use a number of different cameras and lenses, but they’re all “pro-sumer” (a cross between consumer and pro level) or higher. My own camera, the bottom feeder of the bunch, is a Canon EOS 50D, which is a 15-megapixel single-lens-reflex body, shooting through a Canon 70-200 F2.8 L lens. It’s a big, heavy beast but gives good results. For most of the air-to-air images, the two aircraft are close enough that anything from a 70mm to 100mm lens will do. If you have to run out to 200mm, your following airplane is too far away and you’ll lose too many images to camera shake. The subject airplane should fill nearly the entire viewfinder.

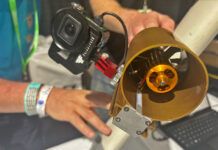

Getting true pro-quality shots is difficult with propeller-driven aircraft for one reason: You don’t want to “stop the prop” if you can help it. This requirement dictates a slower shutter speed, usually in the range of 1⁄90 of a second to as slow as 1⁄30. If you remember your Photography 101 course, you know that these slow shutter speeds invite blurry images overall. Here’s a bit of insider baseball: The pros all use small gyroscopes bolted to the lens. Ha! So that’s how they get those big, blurry prop disks and yet keep the body of the airplane sharp. And you thought they just had steady hands. To make life easier, we ask the pilot in the subject airplane to use maximum rpm for the flight—the faster the engine turns, the more arc the prop makes for any given shutter speed. Three- and four-blade props are the photographer’s delight.

Finally, we don’t get fixated on grabbing just one photograph. Once we have something on the chip that looks OK, we begin experimenting. Don’t be afraid of backlighting: A sunset behind an airplane is as evocative as it gets, and don’t be concerned that the airplane has gone dark. Change the relationship of the airplane in the frame and relative to the background. Notice how the most amazing shots seldom have the airplane smack in the middle of the photo? Composition can add a dynamic element.

Here are two examples of an overcast sky killing all detail and tension in an image. In both cases, the photographers lost the light near the end of the shoot, but grabbed a few on the way in. (They can’t help themselves.)

Back on the Ground

Good photographers will spend as much or even more time shooting the “ground beauty” photos as the air-to-air. Here are a few tips on how to make the best images possible. First, always pay attention to your background. You may think you have a clean shot of the airplane with mountains behind, but look again for telephone poles and the like. Watch, too, for reflections and shadows on the airplane. We love to fly polished airplanes; hate to photograph them. One tip for the ground shots is to step back and use the longest lens you have with the largest aperture. Increasing the aperture (which is the smaller number on the F stop) shortens the depth of field, or the amount of the image that is precisely in focus. Good photographers will use a short depth of field to blur unsightly backgrounds. When shooting close-up details and interiors, experiment with fill flash to add some “pop” to the image.

The final step is culling that chip full of images into ones we actually want to use, a difficult task because we often start with more than 500 frames. About a third can be deleted immediately, a third are workable, and of the remaining third perhaps 25% are worthy of a cover—or that coveted place on the office wall. Take your time when sorting images, and don’t think that Photoshop will fix a poorly exposed, out-of-focus shot. If you didn’t get exactly what you wanted, it’s often best to simply try again.

Our photo shoots often end after dark. In the summer, in Seattle, we don’t get dinner until 11:30—when we’re all dog tired. But days or weeks later, when we see the results of the mission, it’s always a delight to see a pro shooter’s work.