Have you ever thought about becoming a licensed airframe and powerplant (A&P) mechanic, but put the idea out of your head because of the daunting requirements?

According to the FAA website, you can get the experience you need to become a certified mechanic in one of three ways: You can sign up for a two-year program at one of the aviation maintenance technician schools. You can work for an FAA repair station or FBO under the supervision of a certified mechanic for 30 months. Or you can join one of the armed services and get training and experience in aircraft maintenance. Of course, the FAA has to confirm the validity of your logbook entries to verify you meet practical experience requirements before you can take the test.

For many of us middle-aged (or older-vintage) flyers, there’s just too much everyday life going on to put things on hold for two years (or more) to log enough experience to satisfy the FAA and pass the testing process.

Hold on there! The FAA skipped over the relatively new class of Light Sport Repairman. In fact, a Light Sport Repairman with a maintenance rating can take you all the way down the road to an A&P.

The background to this is when the Light Sport Aircraft (LSA) rules came out, the FAA recognized that requiring an A&P for maintenance and inspection of simple Light Sport Aircraft might be problematic. As anyone who owns but is not the original builder of an Experimental airplane knows, it can be a hassle to find an A&P that is both available and willing to do a condition inspection. Proponents of the Light Sport concept understood that adding scores of new aircraft to the maintenance and inspection burden of a limited number of A&Ps could only lead to long waits and high costs. Since the idea of LSA was to make recreational flying more affordable, some special considerations were in order.

In what can only be described as a remarkable example of cooperation between the various stakeholders, including but not limited to the FAA, manufacturers, educational institutions and industry advocates such as the EAA and the AOPA, the Light Sport rules that emerged included two innovative options to train and license Light Sport repairmen.

The first is a Light Sport Repairman Inspection certificate (LSR-I). This is a particularly unique certificate. The training is an intensive 16-hour curriculum over two days followed by a test to confirm you have absorbed and understood the material. Getting a Light Sport Inspection rating allows you to do annual inspections only on your E-LSA. You cannot inspect any other E-LSA. If you sell yours, you cannot inspect it for the new owner. If you buy a different E-LSA, you have to apply to the local FAA field office (FSDO) and have them replace your inspection certificate for a new one specific to your new E-LSA. Most people who take this course already own an E-LSA, but you could take the course in anticipation of purchasing an E-LSA in the future.

While an inspection certificate is a great option for E-LSA owners, the real game changer is the Light Sport Repairman Maintenance certificate (LSR-M). With it you are authorized to perform for hire maintenance and return an S-LSA to service as well as perform annual condition or 100-hour inspections on any LSA. You can look up the detail about both ratings and more in FAA Advisory Circular (AC) No: 65-32A “Certification of Repairmen (Light Sport Aircraft).” There are some basic requirements, such as being proficient in English, but owning an airplane is not one of them. Anyone who wants to work on and inspect an S-LSA can take the course, which is 120 hours.

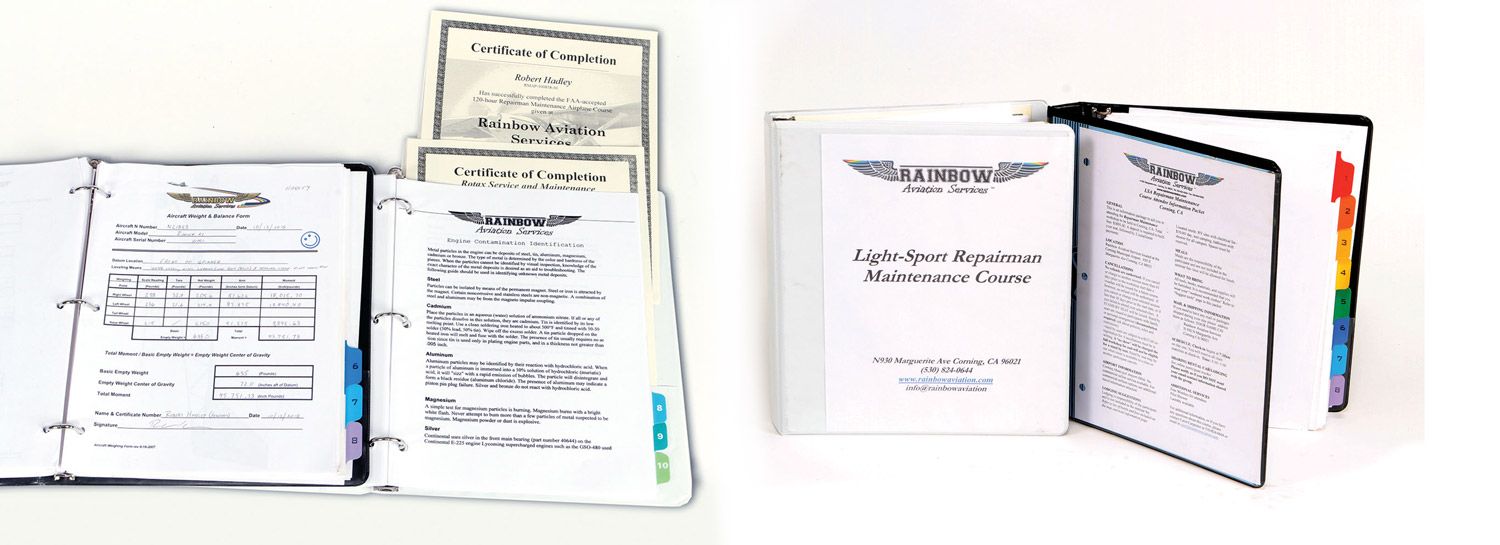

I took the 120-hour course in October of 2018. The class I attended was conducted by Rainbow Aviation, which at the time was located at the airport in Corning, California. They have since relocated to Missouri, and from the pictures that Carol Carpenter sent me, the classroom facilities look like a major upgrade.

There are other operations that provide maintenance training, but Rainbow was the first to get their curriculum approved by the FAA and they probably have more experience teaching the course than anyone.

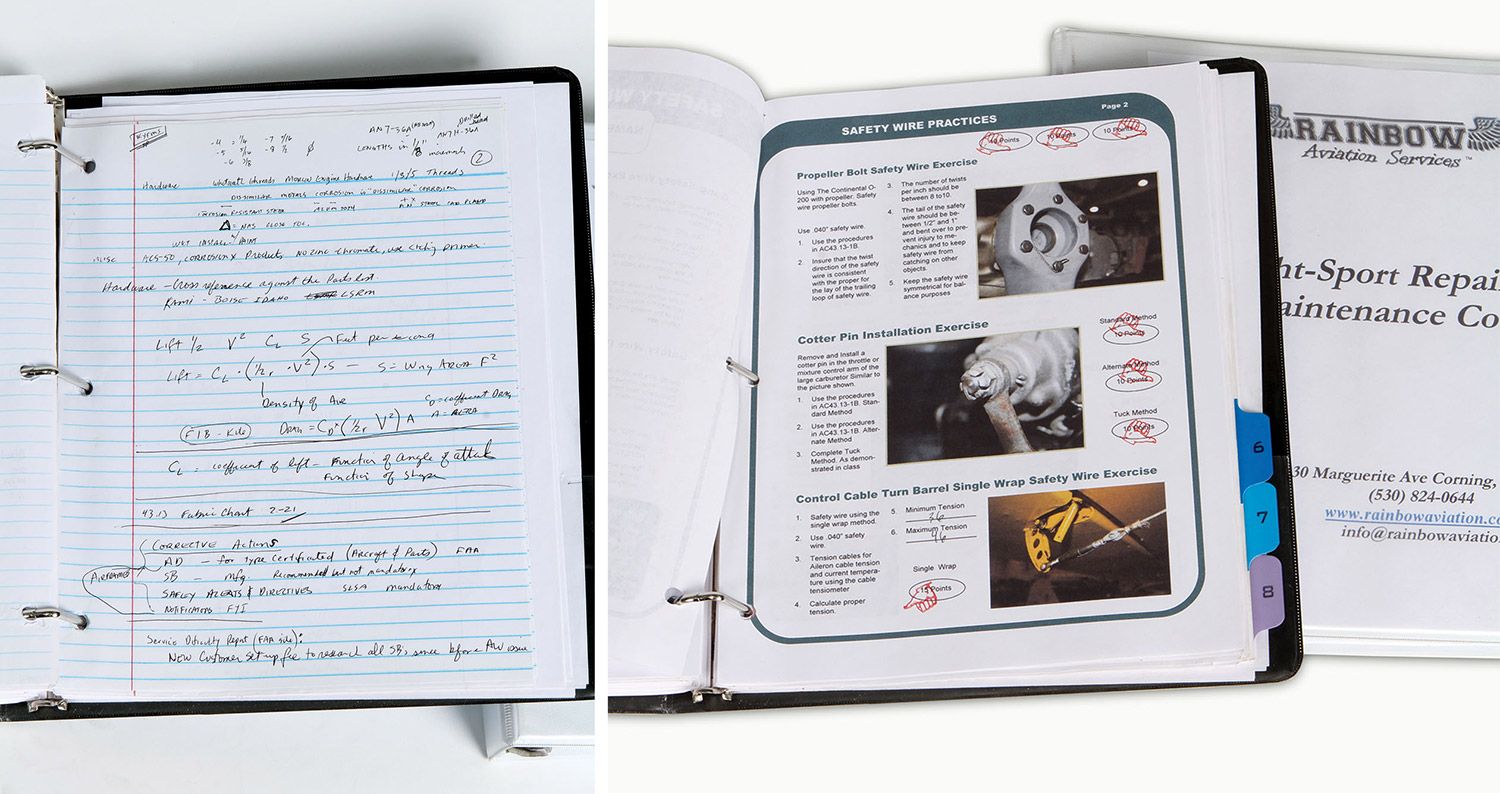

At Rainbow, class sizes are limited to about a dozen students, and the time is split up 65% lecture and 35% practical. The practical training is both in the shop and on the flight line, and you can expect to get your hands dirty.

Upon signing up, I received an email packet with a ton of information on where to stay, the course outline and a questionnaire to help them prepare for my arrival. About six weeks prior to class starting, I received another email with details on what to bring (safety goggles, earplugs, etc.) as well as a series of reference documents on corrosion, hardware and safety wiring that were required reading.

My class was a mix of young and old, male and female. From what I understand, this was typical.

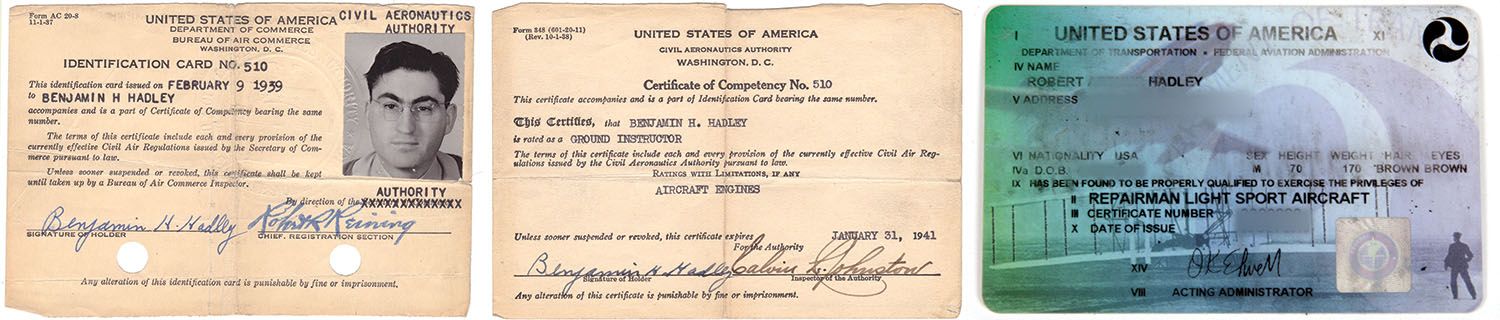

Everyone had a slightly different reason for wanting to get their repairman maintenance certificate. Some had jobs lined up, others planned to do inspections as a side business. The young lady in our class, Ann from Oregon, took the class so she could maintain and inspect her father’s S-LSA. For me, at age 60, it was a combination of factors. My primary reason was there are a lot of E-LSA and S-LSA with Jabiru engines out there, but very few A&Ps willing to work on them. I felt I could fill a niche by being a West Coast Jabiru guy. Another factor was, even though an LSR-M is not the same as an A&P, getting certified as an aircraft mechanic was an homage to my dad, who got his CAA (pre FAA) “aircraft and engine” certificates in the 1930s. (He was certified as an instructor on engines in 1941.) Although he died in 1998, I felt a compelling need to keep the tradition alive.

Lastly, as a certified Light Sport repairman-maintenance, any work you log on an S-LSA, E-LSA or any N-numbered Experimental, including building (as long as the project has an N-number reserved) counts as “being under the supervision of a certified mechanic” and can therefore be applied toward the 30-month minimum for the A&P exam. This is a great option for serial builders. After a couple of projects one could easily qualify for the A&P exam!

For more information visit www.rainbowaviation.com or Google “Light Sport repairman training providers.”

Well written summary. BUT…This article would be improved by including what CANNOT be done with this training, especially for E-AB aircraft. The use of the term “experimental” is unclear and often causes confusion between E-LSA and E-AB. This article continues that tradition by not clearly and always emphasizing and explaining what this training does and does NOT allow for E-AB aircraft. Should specifically reference and clarify rules on who can perform and cannot perform the annual inspection for E-LSA versus E-AB, whether owned or non-owned.

It makes the distinction more than adequately. Read it again. Then feel free to pen another article on the topic of your choice, such as E-AB maintenance and inspections.

The article was not clear to me, as a new owner of an E-AB LSA aircraft, only by omission. You probably already knew this, which is why you think the article is clear. I did read it again.

Thanks Robert for a good written article. It was moving to see your and your father’s licenses side by side.

After retired from Engineering a few years back, I got my LSRM-A, training at Blue Ridge Community College, Weyers Cave, Virginia. It was a very enjoyable experience, that I would highly recommend. In the interest of safety all pilots should gain good mechanical aptitude. I had an engine out at 6500’ once. Sure got my undivided attention. Best glide speed and avoid stalling. You can hang around up there for a surprising amount of time.

What is the support reference for the statements in the last paragraph regarding applicability toward required experience for the A&P certification? Not according to my local IA.

https://www.aopa.org/news-and-media/all-news/2020/november/pilot/maintenance-training-career-gateway

Excerpt from the AOPA link above

“Mike Zidziunas was the first LSRM in the country to earn his A&P under this rule in 2009. He saw the potential in light sport aircraft and enrolled in one of the first LSRM courses offered. He has gone on to leverage the opportunities the certificate presents, opening a Rotax service center, working with manufacturers assembling LSA aircraft, and continuing his training by earning an inspection authorization”

Bob

Thank you. I had no idea.

Hi Mr Hadley. I really enjoy your column in KP. It’s one of the first I read.

I’d like to ask a more detailed question about the 30 month experience to qualify to test for the A&P. I have found in the FARS the statement about working as an LSRM for 30 months, however, I’ve not found anything that confirms that building an ELSA or an E-AB also counts. Is there an advisory circular or a letter from FAA legal that codifies these additional options? I’ve talked to Rainbow and didn’t get a good answer. I’m imagining going to my local FSDO after building a couple of E-AB aircraft over the course of 30 months and having them just look at me funny then telling me there is no such option.

Thanks

Mr. Hadley, could you please cite where in the regs you learned that the time building an E-AB (with an N-Number) while holding a LSRM cert can count towards A&P experience? My ASI is not seeing it and that it throwing my plans off. If you can’t cite it, the article needs to be revised/corrected or other folks will follow it and be seriously frustrated.

About the same time my article appeared (which was several months after writing it and a couple of years after I took the course), the FAA issued guidance regarding what counts toward A&P experience requirements. While building time is no longer accepted, maintenance and repair work done on experimental aircraft does count (but the work must be traceable to an airworthy aircraft — so always log the N number and task in your A&P logbook). Keep in mind that the examiner would review the entries to make sure the tasks represent a wide variety of disciplines.

Check out the below link, which includes additional clarification for the following statement:

“Update October 22, 2020:

FAA Order 8900.1 has been amended since the version quoted below, with the addition of a note that reads:

NOTE: Manufacturing of any type of aircraft, including amateur-built experimental, does not count towards practical experience. However, practical experience gained on amateur-built aircraft after the aircraft has received an Airworthiness Certificate may count.

{This is in 8900.1, Vol 5, Ch 5, Sec 2, Par 5-1134 “Eligible to Test”}”

https://www.kitplanes.com/editors-log-60/#:~:text=NOTE%3A%20Manufacturing%20of%20any%20type,an%20Airworthiness%20Certificate%20may%20count

Thank you for all the great information. Is there any test study prep material available to purchase before taking the class?

The 2023 version of the FAR/AIM book is a good place to start. As I mentioned in the article, if you take the class from Rainbow Aviation (and sign up early), several weeks ahead of the class, they will send you study material.

While it helps to have a some experience with engines and airframes, the course is as much about understanding the regulations as it is mechanical aptitude.