Although not strictly required, it has long been considered good practice to include a restrictor fitting in the oil line between the engine and the pressure gauge or transducer. This fitting should be at the engine end of the plumbing, screwed directly on the engine, so that if the hose or gauge ruptures, the engine will not pump all of your oil overboard too quickly. A small restriction has no effect on the measured gauge pressure of the oil when the system is functional, but it will greatly slow down the rate of oil loss if you have a leak outside of the engine case.

The restrictor used by many is a modified AN816-4D nipple that screws into one of several possible oil sensing holes on the typical Lycoming or Continental engine. The fitting is modified by plugging the passage and then drilling the plug out with a tiny drill—something on the order of #40 or smaller.

You can buy standard AN fittings modified with a restriction from several of the regular supply houses in the homebuilding world, or you can make your own with just a little shop time. Here’s how we do it ourselves.

Start with a standard fitting and an AN470-5 rivet about – to 3/8-inch long—whatever you have handy will work. Take your favorite rivet squeezer and set it up with an AN470 female die on one side, and a flat die on the other. Place the rivet in the jaws with a pair of needle-nose pliers (trust me, you don’t want your fingers in there!) and give the rivet a little squeeze—just enough to expand the diameter of the shaft a little bit. Try the rivet in the AN fitting; if it slides in, squeeze it a little more. You want it to be just enough larger than the center of the AN fitting that you can’t insert it by hand.

Once you have expanded the rivet properly, get out a ball-peen hammer and your back-riveting plate. Tap the rivet into the bore of the AN fitting; if it takes more than a ball-peen hammer, you probably squeezed it too much, and you might split the AN fitting. If it goes in with one tap, you didn’t squeeze it enough. Drive the rivet in until the head sits squarely on the lips of the fitting all around. The shank of the rivet is now tightly married to the bore of the fitting and should never come out.

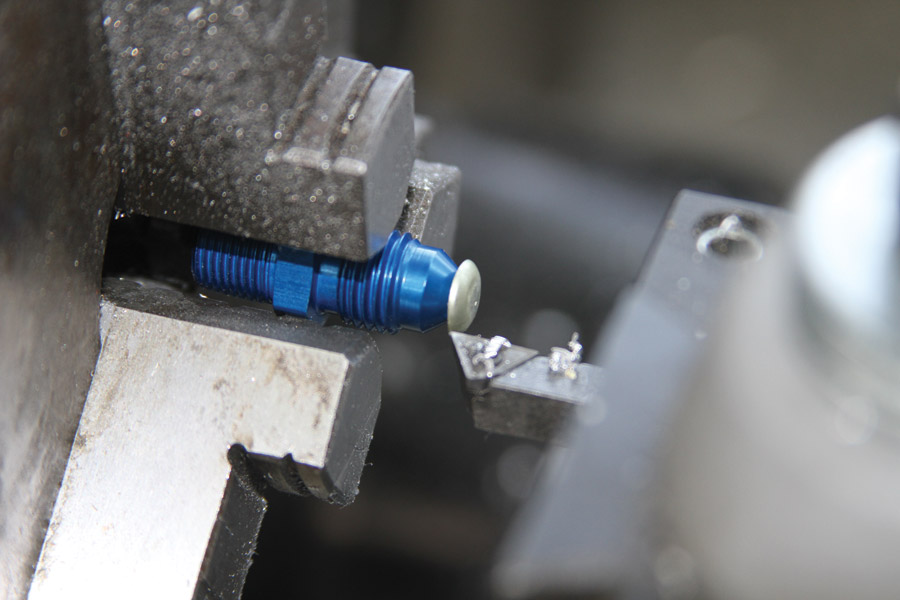

Next, remove most of the rivet head. We did this on our lathe, but you can use a Scotch-Brite wheel (or other method of aluminum removal) to slowly eat away at it until you have it flush. Be careful not to damage the sealing surface of the fitting—go slowly.

Finally, chuck the plugged fitting into the lathe and pick a #40 (or smaller) drill bit to drill out the new orifice. Alternatively, put the fitting into a drill press vice and drill it out that way. Either way, drill all the way through the plug and voil! You now have your very own restrictor orifice.

You can do the same thing with an angle fitting (either 45 or 90 degrees), if that is what you need for your installation—you just won’t be able to use a lathe to remove the head. You can also use a variety of drill sizes to fit your application. Van’s Aircraft uses a #40 hole for their oil pressure restrictor, while some have found that a restrictor with a #60 hole is needed to smooth out the pulses in a manifold pressure sense line. The same technique can be used to produce any size restrictor you need.

Restrictor fittings are important, but they don’t need to be costly. Some folks don’t know they are good practice, others don’t want to spend the money—but rolling your own makes the cost no more than what you’ll pay for the unrestricted fitting in the first place—plus a penny for the rivet and a few minutes of your time.

Lyco O 360 engine on a Glastar. I change the oil pressure gauge VDO type quite regularly, as after 50-60 hours they start to give changing values (without any reason) Somebody suggested to insert a 4AN restrictor into the hose connecting the engine with the oil pressure instrument. Do you think this will solve the problem?

I can’t say if it will solve the problem, but I can’t see it hurting anything. However, if the VDO sensors are getting that short of life, I suspect they are dying from vibration – are they remote mounted, or changing on the engine? Remote mounting is preferred. Or change to a more modern sensor.