Forty-five degrees nose high and climbing. The author (pictured above) asks, “What are you doing, Sam?”

A smart pilot always secures the baggage area cargo. Why? Because you never know when you’ll end up upside down.

Not long ago, I flew a friend in my RV-7A to eat lunch at Cedar Mills Airport (3T0) on the Texas shore of Lake Texoma. In the spirit of E-Mag’s brown bag confessions, I’ll call my friend “Sam.” Now let me tell you a little about Sam. He’s not a professional pilot, but has flown general aviation for decades, including owning a few Cessna 172s as lease-backs. He’s a very meticulous and precise VFR pilot and even flies a steadier heading and altitude than I usually can command. However, all of his flying time has been in Cessnas. He flies the right seat of my Van’s RV-7A quite well, but the RV is still new territory for him.

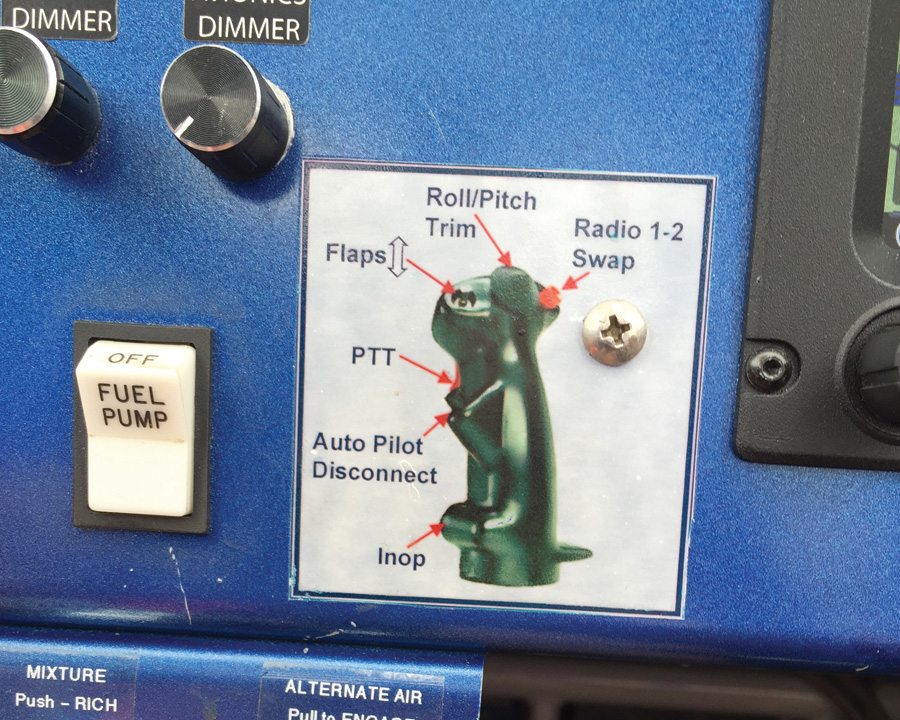

After lunch, Sam and I swung into Gainesville Airport (GLE) to beat up the pattern, then land and fill up with some of the lowest-priced avgas in Texas. I flew the first box pattern, talking him through the configurations, speeds, power settings, and such. After my touch-and-go, he said he’d like to fly a couple. I reminded him that the red “guns” trigger switch on my Infinity stick grip is the push-to-talk switch, and the top toggle runs the flaps. After two reasonably impressive patterns, we full-stopped and gassed up.

For the return leg to Northwest Regional Airport (52F, our home airfield), I urged Sam to fly in the left seat. Sam eagerly agreed. I talked him through an uneventfully smooth takeoff and climb-out southward toward 52F. Actually, I didn’t need to say much of anything, because Sam flew beautifully. I had him climb to 3000 feet and track the aircraft toward the western half of Denton’s Class D, so we could shoot the gap above the Class D, but below DFW’s Class B wedding cake shelf. At the proper range from home plate, I prompted him to make the “10-mile” call on CTAF.

And that’s when things got really interesting in the literal blink of an eye.

The Pitch Trim Loop

Sam made his 10-mile call, although it was sort of a jumbled call as he tried to remember our N-number. While he spoke, I glanced at the PAR-100EX for no good reason other than to make sure the VHF transmit light was blinking. Indeed, I saw no flashing transmit light, so I shifted my glance over to his left hand on the Infinity grip to be sure he was squeezing the red PTT trigger. He was not squeezing the trigger. All of this took about 5 seconds.

I looked up at Sam and was about to point out his radio transmit error…and couldn’t believe what I saw. The horizon behind him was tilted about 45 degrees off level. We were nose high, climbing through 45 degrees and getting steeper.

“What are you doing, Sam?” I asked. The nose kept rising.

“I’m not doing it. You are,” he replied. Uh-oh.

A whole lot of Air Force training kicked in at that moment, starting with my stern declaration, “I’ve got the jet.” (I know, the RV-7A is no jet, but habit patterns are what they are.) He immediately released the stick as I took control while shoving the throttle full forward. We were about 80 degrees nose high now, slowing, as I handled the control stick for the first time. The nose kept wanting to rise, but I still had about 70 KIAS. This RV wanted to loop—and had the speed to complete the loop—so I let the loop continue.

We topped out at 3970 feet MSL according to my Dynon SkyView PFD. As we came out the loop’s back side with airspeed increasing and throttle properly managed, a significant amount of aft-stick load pressed into my hand. “Significant” load, meaning a lot of aft pressure, but not so much that I couldn’t counter it with forward stick. We completed the loop 20 degrees off heading and within 50 feet of our original altitude, wings level, and still managing the aft-stick loading. Mashing the pitch trim coolie hat forward alleviated the aft-stick loads, and I re-trimmed the aircraft for level flight. This was my first clue into what caused our nose-high unusual attitude.

With the aircraft under control, I took a couple of deep breaths and scanned for traffic. We were directly over Denton Airport’s Class D, but we never busted it, nor did we penetrate the Class B shelf overhead. Sam was a little white-faced: He had never flown through a loop, whether intentional or not. I asked him if he’d like to fly back, but he was happy for me to take it the rest of the way home.

We landed, pushed her back into the T-hangar, popped open a couple of beers (tastier than usual, for some reason), and I led Sam through a detailed debrief. As any fighter aviator will tell you, the real learning happens in the debrief, and this event was a human factors smorgasbord. I’ll spare you the finer points and get down to the actual human factors we finally identified.

The Human Factors Debrief

Design was the first up-front factor. They say, with some truth, that no two Experimental aircraft are alike. Like Private Pyle and Joker said, “There are many others like her, but this one is mine.” I designed my Infinity Stick Grip switches’ functions precisely the way I wanted them to work. The gun trigger activates radio transmission, and the coolie hat runs the Ray Allen pitch and roll trim.

However, Sam’s flying time is in Cessnas, and his Cessnas used a thumb-pressed switch to transmit. Therefore, my aircraft systems design presented a hidden upfront human factors hurdle for Sam. I was subconsciously aware of the design factor—I watched for Sam to actually transmit the radio, but we had already stepped onto the first human factors landmine.

Which brings us to regression. A pilot suffers regression when he inadvertently slips back to an old habit pattern that’s inappropriate for the current situation. Consider a Harrier pilot from the ’90s who, after leaving older AV-8As for a non-flying assignment, had just recently requalified in the more modern AV-8B. The older AV-8A Harrier featured a guarded pushbutton to extend the landing gear, but no gear handle. The B-model Harrier also had a similar guarded pushbutton, but it was for emergency stores jettison (and it was positioned right next to the actual landing gear handle). One day, while flying in a four-ship pitchout, this Harrier pilot reverted to his AV-8A habit pattern and pushed the guarded button to lower the gear: However, his AV-8B dutifully jettisoned both empty external fuel tanks into some poor lady’s front yard. That’s regression.

The stick-grip functions placard on the author’s RV-7A panel. The red trigger is the push-to-talk switch.

While Sam made his 10-mile radio call, rather than squeeze the PTT trigger, he regressed to his Cessna muscle memory and pressed what he thought was the thumb-actuated PTT button: It was actually the pitch trim coolie hat. Sam ran the elevator trim fully aft, which pitched the aircraft nose up higher and higher. I didn’t catch the unusual attitude because I had gone heads down to check the transmit light. But why didn’t Sam catch the pitch-up? Because he was heads down too.

Remember that he stumbled his radio call trying to recall our call letters? In the debrief, I learned that Sam also looked inside the cockpit to read the N-number off the panel while I was heads down watching the transmit light. Due to distraction and task division failure, neither of us had our eyes outside minding the horizon.

Finally, I include proficiency and limited recent experience as key human factors in this episode, for two reasons. Sam’s a fairly experienced pilot, but he hadn’t flown much over the last two years. He certainly has no RV or E/A-B experience other than in my right seat. Therefore, right up front, he’s flying in a cockpit and operating environment quite foreign to his more-familiar high-wing experience.

Additionally, Sam had zero proficiency or experience in loops or other aerobatics. In fact, he admitted to never receiving more than basic private pilot training for unusual attitudes, and that was decades ago. Sam looked up expecting to see blue up/brown down, but he found nothing but blue and became disoriented.

Spatial disorientation is a failure to correctly sense a position, motion, or attitude of the aircraft or of oneself in relation to the earth’s surface or vertical component of gravity. Flying air-to-air with lieutenants in F-4 Phantoms gave me a ton of experience swiftly recognizing unusual attitudes and aggressively recovering the jet. Frequently flying aerobatics in my RV-7A meant I knew where my airplane’s energy state lay, and whether it could or couldn’t complete the loop. Sam had none of this experience. By the time I had completed the loop, he was still trying to decide which way was up.

And we got in that situation in less than 10 seconds. On a beautiful VMC day.

Takeaways

Unusual attitude training is vital, even more so in your own aircraft. Learn how to recognize its many forms (uphill, downhill, inverted, etc.), and how best to recover safely and expeditiously. I’m glad I had been flying aerobatics; it instilled in me a more intimate knowledge of my RV-7A’s capabilities. But I didn’t make it up on the fly: I got aerobatics training from Gary Platner, an experienced Navy pilot and CFI with loads of aerobatics experience in RVs and many other aircraft.

Finally, I was shocked at how quickly I ended up almost inverted on a clear-and-a-million VMC day. It’s a good thing I had stowed the bits and pieces in the baggage hold.

![]()

Sid “Scroll” Mayeux has over 25 years of experience in aviation training, safety, and risk management in the military, civilian, airline, and general aviation sectors. He currently trains Boeing 777 pilots, and he built and is flying a Van’s RV-7A.