Pilots often gather to debate and nominate designs in the category of “best-handling homebuilt,” and the discussion can be lively. Few would expect a 95-mph amphibian to be included among RVs and Thunder Mustangs and such. Yet, the Progressive Aerodyne SeaRey LSX could arguably be among the best. Why? Pure goodness—but we’re already getting ahead of the story.

The cockpit. Note the analog airspeed indicator, easy to read in just a flash. In the center console, the two T-handles are the brake (forward) and the throttle (aft). The SeaRey has enough payload for this stylish cockpit, or build a plainer cockpit for more payload. It’s up to you.

The LSX is the latest version of the SeaRey, a two-seat taildragger “flying boat” with aluminum structure, a fiberglass hull and fabric-covered flying surfaces. Engine choices are the Rotax 912, 912S (most common), or the heavier, turbocharged 914—providing 80, 100 and 115 horsepower, respectively.

The new factory digs at Tavare, Florida, north of Orlando. Demo flights are made from the water, of course.

The original design had a shallow V hull, which gave excellent performance on calm water. A further modification, called the B hull, had a deeper V for rougher water. That iteration was finally replaced by the C hull, which is tolerant of a wide range of piloting techniques. The retractable landing gear has evolved from manual through two types of electric gear, and refinement continues.

(More) Evolved Amphibian

Designer Kerry Richter listened to pilots and took on suggestions to improve the airplane’s handling, which is notable in itself. The biggest change is the use of ball bearings throughout the control system to reduce stiction (the force required to break static friction and start something moving) and regular old friction. There are also new gap seals on the ailerons plus a 25% bigger horizontal tail that now has dihedral to keep the tips out of the weeds.

It’s not actually afloat here, it’s aground. Once you’ve waded out, boarding is easy, but you will get something wet.

The result of these changes is that you can fly the LSX with control pressures and the sensuous feel of tiny corrections, with friction in the system notable only by its absence.

The LSX demonstrator cockpit, all lit up. Exotic avionics work just fine with a “puddle jumper,” thank you!

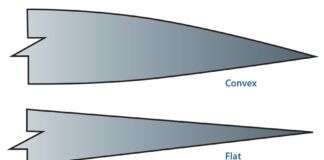

That is just the beginning of the Sea-Rey’s updates. The cuffs on the outboard leading edges that were originally there for spin protection are gone, their function replaced by vortex generators. The wingribs are no longer just top and bottom battens; they are now real ribs with trusses connecting top and bottom, so the bottom surface stays flat at cruise speed with less drag. These wing changes are good for a 3- to 5-mph increase in cruise speed.

Also, the flaps now have gap seals, and there is an inch more chord on the ailerons and flaps, so the stall speed is 7 mph lower. To look at it from another perspective, the LSX stall speed clean is about the same as the classic wing version’s stall speed with full flaps. On water, low takeoff speed is a big deal, because hydrodynamic drag from the hull is an enormous factor in takeoff distance.

For the campers among you or for those who don’t pack light, there is a large, long, tapered baggage area behind the seats.

Jenny Craig Approach

One of the possibilities on the classic SeaRey was a carbon-fiber hull, a $3000 option that saved about 70 pounds of empty weight. On the LSX, the standard fiberglass hull went on a severe weight-loss program without sacrificing strength, reducing the weight advantage of the carbon-fiber hull to merely 12 pounds. That small weight savings is hardly worth the price, so the carbon hull is no longer offered. With the gross weight increased from 1320 pounds to 1430, the Light Sport Aircraft maximum for an amphibian, the structure has been beefed up as well, with 78 changes.

If you want to spend some of that weight savings in the cabin, you can install a slick interior, and there is also an engine cowling that looks good but provides little drag reduction—though it will keep the sun off the rubber fuel lines. An optional 26-gallon tank gives 8 extra gallons, so you can not only fly out to the boonies and back, but you can also fly around while you’re out there. Because the SeaRey is a svelte 850 pounds empty (typically, with minimal equipment), it retains a good payload (428 pounds) even with full optional fuel aboard.

SeaRey interiors can be as plush as you like, and there’s enough payload that you can equip the plane lavishly, carry two, and still be legal.

Not enough improvements for you? Folding wings are well along in development, but they are not being shown because of patent considerations. The goal is for the wings to be foldable by one person in 20 minutes so that the SeaRey can be trailered.

Anchors Aweigh!

I caught up with the LSX at the AirVenture Oshkosh seaplane base, where it was grounded on a sandbar 20 feet out. Shoes and socks off, wade out, climb into the voluminous cockpit, buckle up, and start ’em up. I’d watched Richter depart from this same shallow water location, pivoting the SeaRey in place with blasts of power, and wondered how he did that without forward motion. The answer is that the SeaRey was aground, enabling the pivot. Once aimed in the right direction, a mighty blast of power got the SeaRey going. We kept the sliding windows closed to stay dry, but they can be opened in flight.

From the left (aft): throttle, wheel brake, flap pre-select and gear. A voice reminds you to think about whether you’re configured for water or land.

Conditions were such that takeoffs were downwind over relatively glassy water, which lengthened the run. Takeoff lasted 14 “Mississippis,” but Richter quotes 12 seconds. This SeaRey had the 115-hp turbocharged Rotax 914, giving us a little extra oomph. Liftoff didn’t have that forward surge that you often feel in seaplanes, and the SeaRey just skimmed the waves after takeoff, the ultimate low-level flight. After liftoff, we turned south over Lake Winnebago, enjoying the view of outsized dwellings along the shoreline and wind turbines on the horizon.

First thing, Richter asked if I wanted to see a full-power stall. “Sure,” I said. “Watch this,” he said, taking his feet off the rudder pedals and putting them flat on the floor. With the throttle still fully forward, Richter pulled the stick all the way back and held it there. The horizon quickly disappeared below the nose, and I watched the wingtip assume a 40° angle to the horizon as the SeaRey climbed like an Atlas rocket. After enough time for us to have slowed to the point where things could get really interesting, I looked over at Richter—his feet still flat on the floor, stick full back with both hands, and a “Who, me?” look on his face.

Gap and aileron seals increase cruise speed. For slow aircraft, every little bit helps!

Along about this time, the SeaRey started to nose over toward level flight with the stick still full back, and then it nosed down maybe 20°, regained cruise speed, and leveled off again. Richter released the back pressure for level flight. There are two morals to this story: One, don’t try this in any other airplane, at least any “normal” airplane. Two, don’t try to teach power-on stalls in a SeaRey. Ain’t no point to it.

Richter sweetened the story of the LSX by saying that the company had hired a professional test pilot to do a full spin series, but the best he’d been able to do, even with a CG aft of limits and using every dirty trick in the book, was a one-turn spin before the SeaRey flew out of the spin. For the tests, the SeaRey was instrumented with all control pressures and deflections recorded, as well as the air data. Richter also said that in his own flight testing, he’d not been able to pull more than 3.8 G, presumably because the high-drag airframe—it is an amphibian, after all—can’t build and hold enough speed to pull them.

Shades of the old F-101, the new horizontal tail is 25% larger, and has dihedral to help keep the tips out of the weeds.

Handling Like Crazy

It was time to do some evaluations of handling qualities, but the full-power stall demonstration had already blown me away. The biggest surprise was how sensuous the controls are, allowing you to fly with fine pressures and savor the sensations. You want to maneuver the plane just to enjoy the tactile feedback, like flying an RV or a Pitts, except those will land on the water only once. (Yes, I know there is one RV on floats.)

First came Dutch rolls, slow and fast. On the former, you slowly roll the airplane back and forth while keeping the nose straight; on the latter, you do it rapidly with the rudder in phase with the ailerons. Piece of cake. Slow flight, stick full back? Easy, and you can steer with the rudders all day long. What this means is that the skilled pilot will more readily be able to get full performance from the SeaRey into and out of small landing areas, and the inert pilot will have to work that much harder for a Darwin award.

Somewhere along the way, Richter demonstrated the SeaRey way to do a water takeoff, but this time, he kept his feet on the rudder pedals to steer. He compensated for this pedestrian necessity by taking his hands off the stick after setting 20° of flap and full nose-up trim. With full power, the SeaRey climbed onto the step, accelerated and lifted off. Richter took the stick after liftoff to keep the plane from climbing too steeply. Do this kind of takeoff on a check ride with an unsuspecting examiner and wait for the reaction. If the examiner doesn’t respond, you can always do a water landing with 30° of flaps while not touching the stick. That’s not just a show-off maneuver; it could greatly ease glassy-water landings.

Another part of the demo was step turns. Richter did sharp turns on the step (with the hull planing), using opposite aileron to keep the wings level, pulling maybe a third of a G laterally. This is impressive, and means the SeaRey should excel at circling takeoff from small ponds. The new factory location at Tavare, Florida, north of Orlando, is on a 2800-foot-long lake, plenty big for a SeaRey. Incidentally, first flights from the factory are from water, not land.

Lake Winnebago, headed north toward the seaplane base. The large-format GPS in the middle of the panel was great for airspace avoidance and for keeping track of the route flown.

Come on Down

I did a pair of landings, and with all of the airframe drag, 20° of flap gives you a comfortably steep approach power off, but there’s 30° of flap if you need it. The trick is to either fly the SeaRey onto the water or stall it from no altitude at all. Water is really hard if you drop the landing in and, fortunately, I didn’t. Once on the water, the SeaRey quickly comes off the step, making for a short, er, rollout.

We landed only on water during this evaluation, but a previous flight showed that the SeaRey was well-behaved on wheels. A taildragger, yes, but not particularly challenging. Interestingly,

having a single brake control working both wheels does not prevent the SeaRey from turning sharply on the ground. A cool design feature of the LSX is that the brake lever is located just ahead of the throttle. Push forward on the throttle without touching the brake and you go. Pull back on the brake by itself, and it retards the throttle and gives brakes. For a runup, squeeze the two together, and you get brakes while setting the throttle where you like, at least if you’re not afloat.

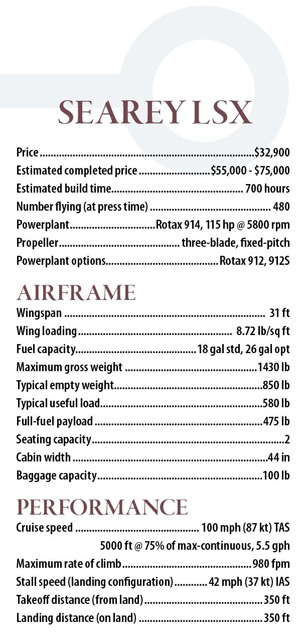

Specifications are manufacturer’s estimates and are based on the configuration of the demonstrator aircraft. As they say, your mileage may vary.

Electric gear is standard on the LSX, and the main advantage is not retraction, but extension. Pushing buoyant tires into the water for beaching could require quite an effort with the manual gear. A nice touch is the optional gear warning system that announces whether you are configured for a water or a hard-surface landing when flaps go out. Standard flaps are manual, but electric flaps weigh only a few ounces more, if you can believe it, and they come with this snazzy four-button control unit.

Compromises, Well Made

Any airplane design is a compromise, as the saying goes, and the SeaRey is as well. Its relatively low speed—95 mph two-way average at low altitude with the Rotax 914 engine—means that if you are going any distance, you will have lots of time to enjoy the great view and the handling. Also, seaplane wings don’t clear docks like the high wings on most floatplanes.

The SeaRey has been landed in 3-foot waves in the right conditions, but it is a small airplane and landings should not be attempted when the waves make a mogul field. Over dinner at the seaplane base, one pilot commented that in the right conditions, even 6-inch waves could be difficult for a plane as big as a Grumman Goose. With all due respect for Grumman’s amazing amphib, it’s likely that the SeaRey LSX is the sweeter handling of the two.

Likely your least favorite view of the SeaRey, it taxiing away without you in it.

For more information, call Progressive Aerodyne at 407/902-9164 or visit www.searey.com.

![]()

Ed Wischmeyer just tripled his average cross-country cruise speed by trading his AirCam for an RV-8A, and the enclosed canopy will let him fly more this winter—such are the joys of living in Iowa.

Love this. Would like to know more about all SeaRey models including approx costs. Would consider a trip to the factory to discuss further and possible make a decision on what model to purchase.