I’m currently in the midst of doing all the riveting of my RV-8 fuselage canoe. I managed to shoot a large proportion of the rivets by myself, which is typical of how I’ve worked on most of the project. I’d say I work solo about 95% of the time.

Fortunately for me, Josie Richard, my lovely partner, also flies and is interested in the build, so when I do need a second pair of hands, she’s a very willing helper. Usually I just need help moving large things, and the times we’ve actually worked together riveting have been pretty rare. About the only big job was riveting the top wingskins, and for that job, I ran the gun and let her do the bucking. It was tedious at times (pretty much the running story of wing building), but we got through it fairly painlessly.

When it came time to flip the canoe over and get back to team riveting, I decided to switch roles. Rather than asking Josie to crawl under the canoe and perform all the contortions, I let her stand outside and run the rivet gun. We made steady but slow progress, but she had a hard time controlling the rivet gun, and so numerous rivets were overdriven and had to be replaced. I was frustrated because I felt like Josie wasn’t concentrating on doing the job right, and she was frustrated because, well, she wanted to help and it wasn’t going well—and, of course, she could sense my frustration, too.

A well-trained helper can make all the difference between a frustrating experience or a productive session in the shop. But it’s up to you to provide proper training.

We crutched along like this for several short sessions, and I thought seriously about having someone else come help. But when I really sat down and thought about it, I was asking a lot of Josie. She hasn’t done a lot of work with the gun and wasn’t going to have that acquired feel of “that’s about right for this size rivet.” Yet here I was, dropping her in deep water and leaving her to shoot, while I attempted to grunt useful instructions from inside the canoe. Throwing my hands up and kicking her out of the garage was hardly helpful. Instead, I decided that we’d stop working on the fuselage and have a training session.

Practice, Practice, Practice

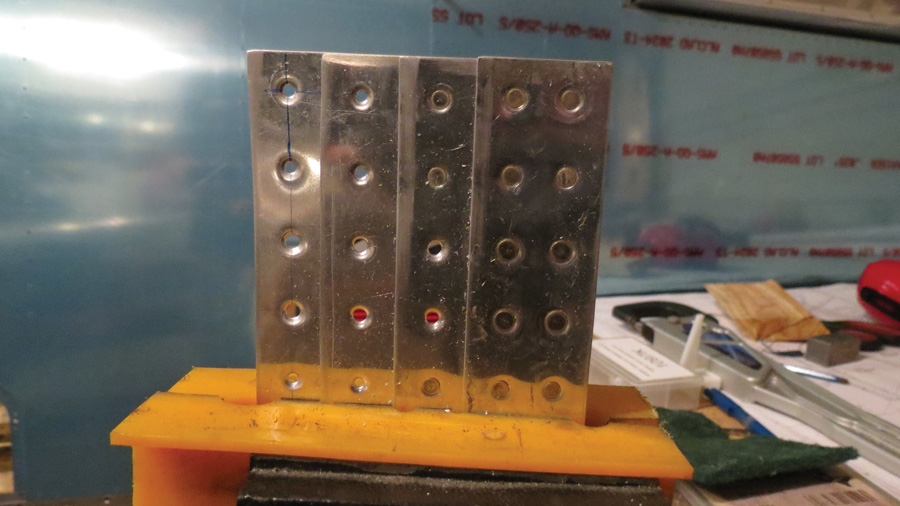

After work one day, I grabbed some scraps lying around, drilled and dimpled lots of holes, and clamped the pieces in the vise, where Josie could shoot and watch the rivet head form. This was the same way I learned. For me, having that instant feedback was a huge help, much more useful than repeated grunts of “a little more…OK, a little more again…”

Notice how I put my middle finger behind the trigger of the rivet gun. This technique works great for me, but didn’t work at all for my helper.

She did better, but still not great. Lots of rivets were overdriven, and we both ended up frustrated…again. I started having thoughts of giving up on Josie again, but quickly realized it would be more productive to start thinking about ways to help her. I ended up realizing a couple of things: First, it was obvious that my method of controlling the rivet gun wasn’t working for Josie. The way I control the gun is by putting my middle finger behind the trigger, as shown in the photo.

I always thought of that middle finger as pushing back against the index for more control, but upon further thought, it was acting more like a limiter on how far I could squeeze the trigger. There was just a bit of travel before my finger started getting squeezed, which made for a natural limit. Knowing this, it was clearer why Josie was having trouble—her smaller fingers wouldn’t be nearly as effective here. I started thinking of ways to add a little bump stop behind the trigger, but then realized the second, more basic problem: I was running too much pressure to the gun.

I took some scraps, drilled and dimpled lots of holes, and clamped them in a vise so my helper could practice riveting and see the shop heads being formed.

I do have a regulator on the gun, but I generally run it close to wide open. This isn’t a problem for me. For one thing, I have my middle-finger technique, which lets me have fine control. For another, I’ve shot thousands of rivets at this point. I’m pretty well adjusted to using the gun like this.

But Josie? I’m not sure, but I quite possibly made things worse by showing her my riveting technique. With less natural ability to limit the trigger, it took only the tiniest twitch—and less than a quarter-second—for her to go past “just right” and end up overdriving the rivet. I might as well have taken a kid shooting for the first time and given him a micro Uzi on full auto.

A Better Idea

Before the next session, I went out and adjusted the pressure to the gun so it was impossible to run it in such a way that you could instantly ruin a rivet. Then I made up some more test pieces and let Josie shoot a bit more. Much better!

I rolled up under the canoe and we went to work—and we had nothing but beautiful rivets that night. From that night forward, riveting sessions quit being frustrating and became much more enjoyable (well, mostly).

Moral of the story: What works for you may not work at all for your helper. It’s up to you to be sure you give them the tools and training they need. Your helper may not know enough to say “this thing is hard to use and I think it’s wrong,” so you, as the experienced builder, have to be able to step back and look at things from the perspective of someone inexperienced.