Uncountable amateur-built aircraft designs have debuted their possibilities on the Oshkosh greensward since EAA moved the annual aviation gala there in 1970. Very few of this multitude are still being built today. One of these rare birds this year celebrates its golden anniversary, the KR series introduced by Ken Rand in 1972, an often-overlooked innovator that gave builders a new construction method and guidance. (The other design celebrating 50 years was the brainchild of one Richard VanGrunsven, but we’ll get to that in a future issue.)

Uncountable amateur-built aircraft designs have debuted their possibilities on the Oshkosh greensward since EAA moved the annual aviation gala there in 1970. Very few of this multitude are still being built today. One of these rare birds this year celebrates its golden anniversary, the KR series introduced by Ken Rand in 1972, an often-overlooked innovator that gave builders a new construction method and guidance. (The other design celebrating 50 years was the brainchild of one Richard VanGrunsven, but we’ll get to that in a future issue.)

Innovation supported by continued creativity is what usually sustains designs. But Ken Rand died on January 31, 1979. Flying his VW-powered KR-2 prototype home from Sun ’n Fun, he found himself VFR high above impenetrable Southern California weather. Working the radio, he sought a solution until the fuel ran out. Ken Rand was just 47.

In the March 1975 EAA Sport Aviation that featured the new KR-2, Jack Cox called Stuart Robinson, Ken Rand’s partner in design and Rand-Robinson Engineering (RRE), “the invisible man.” Dedicated full time to selling plans, parts and material kits for the KR-1 and KR-2, he decided to move north to a small town 150 miles east of San Francisco, said Jeannette Rand, Ken’s wife and RRE’s business leader. “He visited the office a few times after that, but I’ve lost track and I haven’t been able to find him.”

What’s sustained the design and its evolution over the past half century is the community of KR builders who gather online at www.KRnet.org. The free email list, generically known as the KRnet, is the go-to information source and archive that includes virtually all related information, from the builder’s newsletter that preceded the online community to links to the 27 websites of KRs under construction as well as 61 pages of flying KRs.

What makes the KR’s golden viability even more remarkable is that builders must bring them to life from plans. Its existence today is the elusive combination of affordability, performance and ease of construction when Rand introduced foam-and-fiberglass construction techniques on the KR-1 in 1972.

Crafting the KR-1

Illinois born and raised, Ken and Jeannette Rand met as freshman business majors at the University of Illinois-Carbondale. They married the next year, 1955, and started their family that would grow, in time, to three daughters. “Ken wanted an [electrical] engineering degree, so we transferred to [the University of Illinois at] Urbana-Champaign.”

Rand went to work for Douglas Aircraft at several of its Southern California facilities, from Santa Monica to Vandenberg Air Force Base, before transferring to Long Beach, where he met Stu Robinson, where they were both McDonnell-Douglas flight test engineers.

Becoming fast friends (Ken was Stu’s best man), they started building an airplane in 1968, Jeannette said. They started with John Taylor’s JT-1 Monoplane design, a homebuilt that required minimum tools and average skills that first flew in Essex, U.K., in 1959. Ken remade it using the foam-and-fiberglass construction method he’d used on his control-line flying models.

As Jack Cox described the KR-1’s Oshkosh 1972 debut in the January 1973 EAA Sport Aviation, “Ken Rand’s Styrofoam airplane” had a plywood and spruce box fuselage affixed to a 5-foot-5-inch wing center section with main and secondary spar carry-throughs that supported the seats, right-side stick and retractable main gear. The 17-inch main wheel struts retracted straight back, with the 8-inch go-kart wheels absorbing bumps and scrubber brakes to slow it down.

The KR’s foam-and-fiberglass compound curves revolutionized homebuilding and inspired subsequent creations by designers. Lance Neibauer, a graphic artist who later created the Lancair line of homebuilts, bought a set of KR-2 plans early on and did graphic work for RRE as well, said Jeannette.

In conventional KRs, builders created the 7.5-gallon fuel tank between the instrument panel and firewall, turtledeck, vertical and horizontal tail and outer wing panels with polystyrene foam glued to the wood spars and structure, trimmed and sanded to shape, with Dynel cloth (soon replaced with fiberglass) epoxied in place and sanded smooth.

Three hinged cockpit toppers gave builders a choice: an open-cockpit windshield, an enclosed razorback turtledeck or a full bubble. To shape the tight-fit cowl, builders glued foam to their VW powerplant, carefully carved and sanded it to shape, then sawed it off, split it in two and hollowed it out as necessary. (The next time you complain about having to trim your prefabricated, quality molded cowling to fit your kit’s airframe, remember this.)

Popular Mechanics wrote about the KR-1, the “Homebuilt ‘model’ plane you can really fly,” in March 1973, and it was on the cover of the October 1973 Science & Mechanics magazine, proclaiming it a “MAN-CARRYING MODEL PLANE!” with a bullet list of features: “Build it for $495 (including engine). VW powered. Trailerable. 310 pounds. Styrofoam construction.” Then Air Progress put the bubble canopy KR-1 on its March 1974 cover.

When the post office started delivering “not stacks, but big bags” of orders for plans to the house, Ken and Stu decided to form Rand-Robinson Engineering. Jeannette, the business major, told them, “If you’re going to do it, you’re going to do it right. The guys were still working for McDonnell-Douglas, but they got so busy they had to quit and run the business full time.”

Room for KR-2

Introducing the side-by-side KR-2 in the March 1975 EAA Sport Aviation, Jack Cox noted that RRE has sold more than 5000 sets of KR-1 plans worldwide. Rand, who stood 5-foot-5, said Jeannette, and Robinson, an even 6-footer, both flew the compact KR-1. The KR-2 employed the KR-1’s tail feathers, landing gear, wheels and brakes. The fuselage was 5 inches longer aft of the firewall and the cockpit was 38.5 inches wide.

The span of the fat RAF 48 airfoil grew to 20.7 feet. Using the same structural member thickness, the designers reduced the KR-1’s 12-G calculated safety loading to 9 G’s at a 900-pound gross weight. Despite the growth, the prototype KR-2, N4KR, weighed just 430 pounds empty.

To ensure the KR-2 was adequately stressed for smaller VW engines, RRE mounted the biggest VW then available, the 1834cc Revmaster. Producing 60 hp and turning a Bernard Warnke ground-adjustable prop, at 3200 rpm it indicated 180 mph. The 10-gallon fuselage and 2-gallon tank in the right wing root fueled the flight to Oshkosh 1974.

With no electrical system, a battery (replenished overnight with a trickle charger) powered the transfer pump and radio. Conversations about Kansas weather didn’t leave enough battery to transfer fuel. Setting down outside of Topeka, Rand ran off the ranch strip and broke the gear legs. The KR-2 arrived at its Oshkosh debut on a trailer, and its repairs became a how-to forum on composite construction.

Spurred by interest in the KR-2, RRE introduced its next innovation, a 64-page illustrated building manual. They hired a professional tech writer, Jeannette said, after subdividing the building process into short, sequential paragraphs keyed to 25 drawings and 81 photographs. Rand-Robinson Engineering soon supported the KR-2 with nine material kits.

RRE’s KR-2 wasn’t the only one at Oshkosh the summer of 1974. Joining it was N100MW, built by the Wicks Organ Company of Highland, Illinois, in just 74 days. Cox called it “more representative of what builders will do with their own projects.” With a larger 80-hp 2100cc Revmaster, a full electrical system, interior and heel brakes, it weighed 555 pounds empty, 125 pounds more than the prototype.

A renowned organ company founded in 1906, Wicks built its KR-2 to further its aircraft building supply business that first focused on the Sitka spruce used to build pipe organs and airplanes. The demand that followed the KR-2’s debut gave life to Aircraft Supply (now Wicks Aircraft and Motorsports), said Scott Wicks. “It moved from a small 1500-foot supply area in the organ company to a 30,000-square-foot custom-built facility across the street.” (Wicks no longer lists KR material kits on its website, but it still offers all of the materials.)

RRE added an electrical system after Oshkosh 1974 and then added a turbocharger that did not need a wastegate, said the April 1976 EAA Sport Aviation. Revmaster bent the pipes and dyno-tested the engine. Closing the opening where the right exhaust pipes exited the cowl was the only other change.

Burning 4 gph, the turbo pumped 28 inches on takeoff. The plane lifted off at 50 mph, climbed at 800 fpm and cruised at 140 mph at 30 inches and 3100 rpm. Rand did increase N4KR’s total fuel capacity, adding two

14-gallon wing tanks to the 10-gallon fuselage tank, giving it 9 hours’ endurance. He also added a transponder and oxygen for high-altitude flights.

New Wheels & Wings

With Ken’s passing and Stu’s departure, Jeannette said, “There were no longer any engineers at Rand-Robinson Engineering, so I’d run my technical questions by Bill Marcy,” an engineer who had a consulting firm. This led to the KR-2’s fixed conventional landing gear, which was aerodynamically more efficient than the retracts.

Dan Diehl built the third KR-2 to fly, and he faithfully followed the retractable conventional-gear plans, except for the canopy. Gullwing doors made room for his 6-foot-2 father, said the July 1980 EAA Sport Aviation. In his Tulsa shop, he made KR parts and designed a VW accessory section that scavenged oil from the turbo and mounted a 20-amp alternator and starter. Diehl built and sold other KR components, including wing skins and composite fixed gear legs for conventional and tricycle KRs.

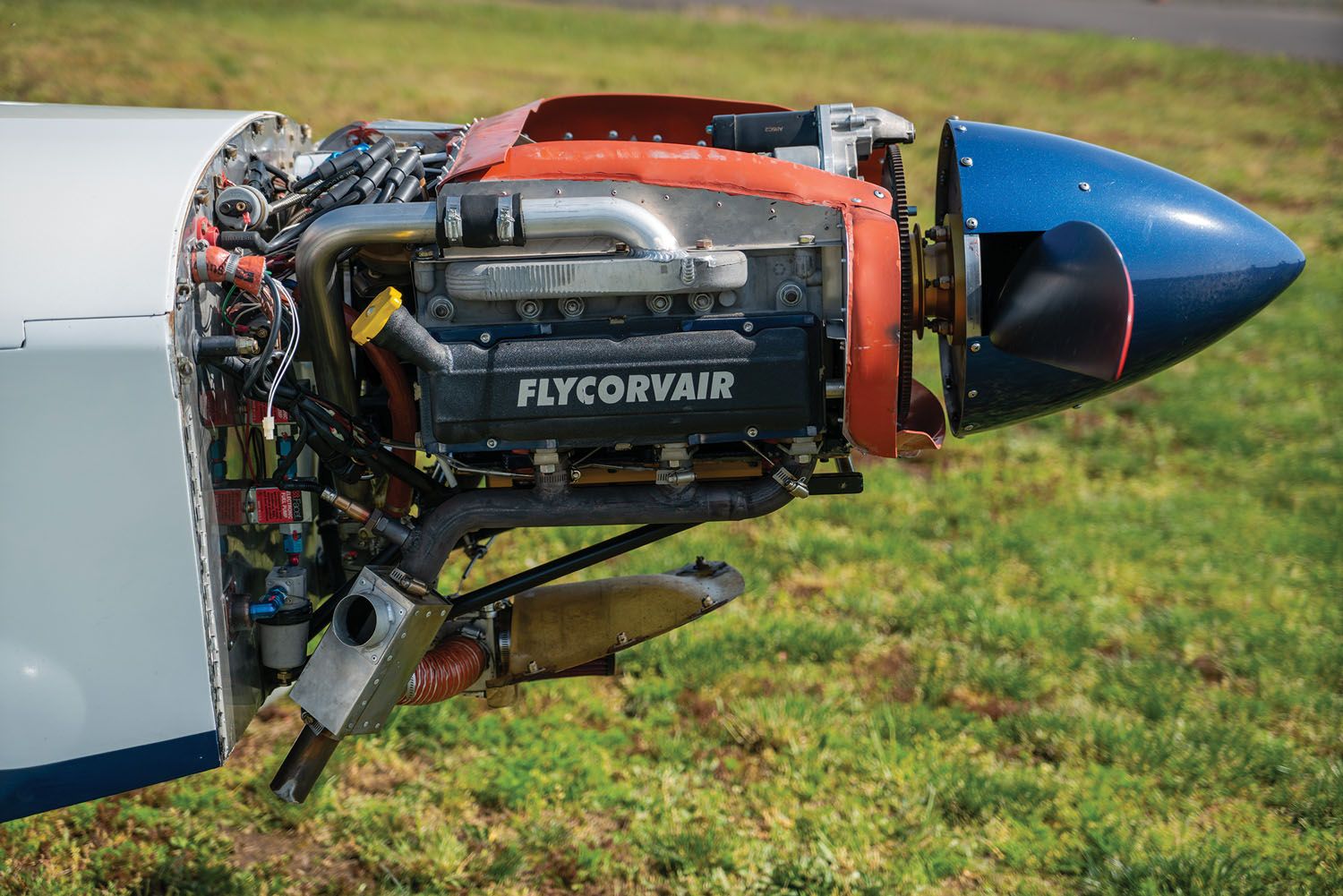

As the KR entered its 30s, it got longer and wider, with fixed landing gear and Cleveland or Matco wheels and brakes. Builders started replacing VWs with Corvairs, Continentals and other similar-sized powerplants. Key to getting the most out of the more powerful engines was a new airfoil, said Mark Langford, who employed it on his Corvair-powered KR-2S.

Created in the 1920s, the RAF 48 airfoil “was designed for an airplane that could do 80 [mph],” said Langford in the December 2006 EAA Sport Aviation piece on his airplane. Langford is the longtime administrator of the KRnet, and one of its members, Steve Eberhart, worked with professor Michael S. Selig, head of the UIUC Applied Aerodynamics Group at Ken Rand’s alma mater, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, to design a modern laminar-flow airfoil and wing for the KR-2. The new wing wasn’t the only change Langford made to his airplane, with every aspect of it, including performance data, documented on the airplane’s website, www.n56ml.com.

Stretching the KR-2S

Builders have been modifying the KR-2 since RRE introduced it, and they were the force behind the KR-2S, Jeannette said. Builders who were making it longer and wider would call and say the parts they bought from RRE didn’t fit. “That’s because the premolded parts were made for [an unmodified] KR-2. Roy Marsh wanted to do a stretched version, and we used his airplane [N133RM] to pull all the molds for the KR-2S.” Instead of drafting a new set of plans, RRE offered supplemental plans that showed where to make the necessary changes.

As described in the January 1995 KITPLANES®, the KR-2S is 1.4 feet longer, with 14 inches aft of the instrument panel and 2 inches ahead of it, increasing the legroom and improving the center of gravity. The new turtledeck and canopy added 3 inches of headroom over the cockpit that was 2 inches wider. Marsh displayed the longer KR at Oshkosh 1994 and went on to win the under 100-hp class of the Sun 100 air race at Sun ’n Fun, clocking 190.4 mph on an 80-hp Turbo Revmaster 2199DT.

Another KR builder, John Bouyea, visited Marsh’s shop while he was completing N133RM. After spending the afternoon in Marsh’s garage shop, “I knew that if he’s doing it, I can do it, too,” Bouyea said. “People were stretching the KR before 3RM became recognized as the first 2S, but Roy was working closely with Jeannette on the design changes. Roy said his son was an aeronautical engineer and was working with him to change some of the design’s issues, being pitchy or sensitive.”

Its affordability is what attracted Bouyea (and thousands of other builders) to the KR. “It offered a lot of bang for the buck, and it looked like something I could build with my skill set.” Buying his KR plans from RRE in 1987-88, he built a KR-2S following the plans supplement prototyped by Roy Marsh’s airplane. “Then I ran across Roy Marsh’s 2S for sale in New Zealand…so I seized the opportunity to buy it,” he said. (More about this story on Page 14.)

Since getting the airplane home he’s upgraded it with ADS-B, a Dynon EFIS and autopilot. “No one has seen this airplane since it went away in 2007, and I want to fly the bejesus out of it,” especially to Oshkosh and the 2022 KR Gathering in September.

Building Community

The vitally important KR community, as many do, started with a printed newsletter produced by a series of editors over 30 years or so, said Langford, a mechanical engineer who works for an aerospace company in Huntsville, Alabama. An AOL group email list followed. The KRnet was the natural extension of that, and when he started it, he scanned all of the printed pieces so anyone can read them.

KRnet is the main conduit where builders of all experience exchange information, though there is also an active Facebook page for the design as well. KRnet is where prospective builders can search out a set of plans from builders who bought them but never finished their projects. “Our plan is to make a full set of plans you can download for free,” said Langford, a CAD master who modeled his airplane when he started his experimentation and shared them with the UIUC team that developed the new wing and airfoils.

“When I closed down the company in 2009, I didn’t feel good about letting it go anywhere else,” Jeanette Rand said with a mournful, melancholy note in her voice. Noting that she retains all rights to the designs, “I have an emotional attachment to it. I really wanted it to rest in peace.”

After Ken died, Ken and Marie Brock started making all of the metal parts for RRE, Jeannette said. When Ken Brock died in 2001, RRE had to find another fabricator, but it was never the same. When Jeannette closed RRE in 2009, she sold all of the tooling and molds to nV Aerospace and authorized its owner, Steve Glover, to fabricate and sell components made with them. Despite developing a number of kits, Glover said builder interest never returned much on the investment. Today, Aircraft Spruce sells raw material kits and nV Aero has plans, $205 for the KR-2 and $325 for the KR-2S.

“We’re providing parts, but we don’t sell much of anything,” Glover said. With no on-hand stock, all parts are made to order, with the price determined by the contract part supplier, who starts fabrication when the deposit clears. In 2018, nV Aero advertised the company for sale. “It is still for sale, and I’m happy to sell everything,” all the tooling and molds, and that fills a 50-by-55-foot hangar.

No one is now authorized to duplicate KR plans, said Jeannette, who turns 85 in July. “The thing is, no one is following the KR-2 plans anymore, even if they have them. Mark Langford and John Bouyea want to redo the plans, but they are not redoing them—they have redesigned the airplane. As I said to them, [their updated design] is not a KR-2 anymore, so they need to rename it and take credit, and accept responsibility, for doing it.”

At 6-foot-4, Larry Flesner is the KR community’s tallest pilot, a feat made possible by the 24-inch stretch of his O-200-powered KR-2S. He’s more proud of attending all but one of the annual KR Gatherings, and he’s hosted 12 Gatherings at Illinois’ Mount Vernon Outland Airport (MVN), the site of the 2022 event. “I missed the one in California. I was going to meet up with Mark Langford and another builder from Pennsylvania. Mark had an electrical issue and canceled.” After checking the weather, he also pulled the plug. “It was blowing, and I was afraid I’d end up as a tumbleweed after spending 13 years building the thing.”

The Gathering location rotates, but with the supportive MVN staff led by Chris Collins, it keeps returning there. Sponsored by the KRnet, Wicks Aircraft and Motorsports, Aircraft Spruce and Specialty and EAA, the Gathering will celebrate the golden anniversary of the KR September 8–10, and the event will run in parallel with the Light Sport Expo event.

“Officially, they run Friday and Saturday, but the diehards show up on Thursday,” Flesner said. Everyone is on their way home on Sunday. But with the events forums, presentations and KR side conversations, no one leaves with unanswered KR questions.

Epilogue

After 50 years, the KR design endures, even without traditional factory support and the long passage of time since the originators have passed on. Something about this good-looking, fun-flying airplane keeps enthusiasts building and flying their KRs. It’s been said that the “modern” aircraft builder is more of an assembler than a builder/designer/modifier. If that’s true, it’s good to know the experimenters are still with us, keeping airplanes like the KR alive. Whether they had this in mind or not, we owe Ken Rand and Stuart Robinson a hearty thanks for such a durable platform of dreams.

See walk-around videos of Chris Pryce’s “KR-2S-ish” and John Bouyea’s KR-2S airplanes in detail.

Photos: Jon Bliss, Marc Cook and courtesy of the builders.

Thanks for posting pictures of my cockpit in the KR at 50 article.

Made my day!😎

Chris Gardiner

Thank you very much ! There is a lot here that I didn’t know. Many years ago I bought a set of KR-1 Plans delivered by the hand of Jeannette Robinson at the Hunington Beach Airport. The daunting price $65 ! They have travelled over the world, and are 3 ft away as I write this note.

All the Best, Ron

I had the fortune of knowing Stu Robinson when he lived in Twain Harte close to Sonora in the California foot hills.

He has passed since, but he told me a lot of the details in the early years.

Airplane building in those years was a matter of constructing every spar, ribbon and surface.

I moved away from Ca in 2011, and got an e-mail from one of his kids that Stu had passed not long after…..

Stu worked as an entrepreneur …flipping houses in the area, he had restored around seven houses, when he started to work in a Limestone mine, where I met him, and we became friends.

He had a big shop on his property, with a lot of KR stuff from that time.

I have no idea why he wanted to break up with Ken at the time, if there was a controversy, he didn’t tell.

It seems like Ken and Stu was in contact pretty much to the end at least occasionally..

Stu told that there was no witnesses to the crash except one that claimed he had heard the airplane in the fog passing by, but never saw him. It was too much fog. He never heard the crash though, and that was the last witness until the crash site was found.

According to Stu, he was calculating much of the aircraft, and he was alwsys the background man. Ken was the salesman, the public man, the media man…and that suited Stu.

Only controversy they had, that he told me about, was that Stu had calculated the CG in a much more narrow band , but Ken changed it back.

Other than that, he never really told about negatives, he seemed to be happy during his “KR time”.

I posed the question to him…why, if the whole affair was on a great upswing, and business was going up…why would anyone in his right mind just make a clean break like that…?

He never gave a really satisfactory answer and I didnt want to press the issue…it was after all not my business, just curious….so I dropped that line of inquiry.

When Stu took up the first KR1…he did a couple of test flights…and lost the canopy …with wind in his face and teary eyes, he managed to bring it down.

He claimed that this was the era when it was pure fun, and no one was thinking of suing anyone….he met all the “big names” from that era. Most of the companies selling plans and kits, didn’t survive the onslaught of judicial lawsuits that came in the time period just after Stu left.

Stu was a great man , and extremely intelligent. We could talk Einsteins theory or Quantum Mechanics or whatever, but even in ordinary physics..,he surprised me more than once with his simple and logic explanations.

By the mid 2000, around 2005 I would say, he started to deteriorate in both body and mind. His last years he spent with his eldest son as a caretaker, and passed just a few years after I had moved out of Ca.

A memorial was held…and with Stu Robinson went the last of Rand Robinson.